News

How many Udaras are left orphans after the December 2004 tsunami?

Has the State failed in its duty towards the children left without parents after the tsunami, discarding them to a personal whirlpool of misery and fraud by their foster parents?

This is the issue which comes to the fore in the case of A.H. Udara Chinthaka de Silva of Seenigama, Galle, who was 12 plus when the tsunami of December 26, 2004 left him an orphan.

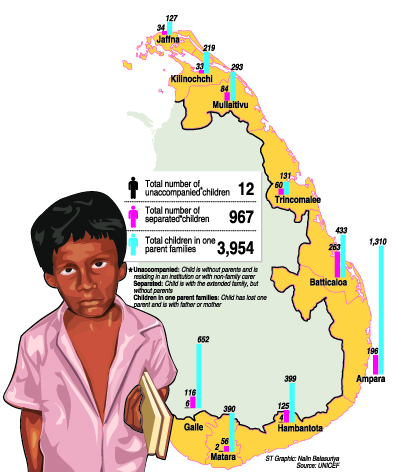

Is he the exception to the rule or has a similar plight befallen all such children left parentless across many districts, after the tsunami? Even the data on these children are difficult to come by, but the report released by the Committee on Public Enterprises (COPE) refers to 2,661 ‘children affected by the tsunami of which 264 had been provided the foster parent facility. (See box)

In the case of Udara, after the initial flurry of ‘caring’ in 2005 and 2006 and the renewal of foster care in 2009, it has taken many long years for the ‘guardian’ of these children, the National Child Protection Authority (NCPA), to shed its lethargy and come out of hibernation and act. The action has followed only after numerous complaints by Udara’s paternal relatives. The ‘monitoring process’ of children such as Udara seems to have collapsed and these children left solely under the control of their foster parents.

On Friday (August 2), at the ‘Foster Care Evaluation Panel’ convened by the NCPA in Galle, a decision has been taken not to close Udara’s file, even though he is 21 years old now, but seek instructions from the Attorney General’s Department as Udara is being treated for mental illness, the Sunday Times learns.

The other crucial decision has been to seek the annulment, in the District Court, of a land deed transfer allegedly after a sale of a 5½-acre coconut property owned by Udara, it is understood.

But is it too little, too late, is the query of child rights activists.

Udara’s tale is similar to that of hundreds of other children who suddenly found themselves all alone in the world. Tossed and dashed around by the first massive wave, Udara clung to a tree. When the wave receded, he ran towards the sea in search of his mother, but the merciless sea rammed the area with the second wave. He then held on to a light-post and once the waters went down, straggled bruised, wet and confused, along with several others, to the Meetiyagoda temple.

There were no signs of both his father, A.H. Sarath de Silva, and mother, A.K. Gnanalatha. Later his father’s body was found but there was no trace of his mother.

Udara was all alone.

Vaguely he remembers that about a week later Probation and Child Care officials took him to the Kitulampitiya Children’s Home. Although his father’s sister (paternal aunt), Ramani de Silva, came in search of him, his family had been estranged from the father’s side and it was his choice to seek the security of his bappa’s house. This was the home of his mother’s sister (maternal aunt) and he went there willingly.

By August 2005, foster care and custody of Udara were assigned by the Magistrate’s Court to his maternal relatives. (See box)

The discrimination began then, alleges aunt, Ms. de Silva, explaining that Udara was sent to a “small school” while the four children of the foster parents attended prestigious ones.

With attempts to contact him being futile, it was only in December 2011 that she saw him again while she was on a visit to her property at Seenigama, adjoining his. “I realised that he was unhappy and that something was wrong,” she says. She then gave her nephew her business card and urged him to call her any time. He did just that in January 2012, pleading with his ‘Chuty Nenda’ to lend him Rs. 100,000 to get back his “bhadu deepu” (leased) property. Being a lawyer, Ms. de Silva says she became suspicious and started looking into matters linked to Udara. He had sat the Ordinary Level exam but dropped out halfway through the Advanced Level studies.

When asked by the Sunday Times why he dropped out of school, Udara says, “prashna awa”, explaining that there were problems. He couldn’t sleep and he was frequently assailed by headaches. He was also being pressured by his Bappa, Udara alleges, to sign documents to lease a land that he owned.

By July 2011, he says, he was forcibly taken to a lawyer’s house and compelled to sign some documents. When he wanted to read what he was signing, he was told curtly that it was a “badhu oppuwa” (lease deed) and he needn’t read it.He was disturbed. He didn’t want to go to school. Remembering the business card, he called his aunt. When his foster family realized he was in contact with Ms. de Silva they smashed his phone, he says.

Pointing out that his mental problem will clear up if he works, his foster family sent him to a garment factory in May 2012.

Ms. de Silva, meanwhile, had gone to the NCPA which is the guardian of Udara, in early March 2012 and handed over a complaint to the Legal Division. Although the officers assured her that they would inform NCPA Chairperson Anoma Dissanayake, nothing happened, she reiterates, making serious allegations against the Legal Division and one particular legal officer of not only incompetence but of willful negligence and callousness against tsunami orphans.While, Ms. de Silva kept calling and paying visits to the NCPA, Udara’s situation worsened. It was in July 2012, when she told the NCPA that Udara was reportedly suffering from mental issues that the long-delayed Foster Care Evaluation Panel was convened on September 4 and 11, 2012.

Chaired by NCPA’s Deputy Chairperson, Sujatha Kulatunge the discussions were heated with NCPA officials accusing her of “trying to rob the property of my nephew”, says Ms. de Silva, adding that Ms. Kulatunge was adamant that Udara’s foster parents could not be changed.

Finally, Ms. de Silva was able to meet NCPA Chairperson Mrs. Dissanayake on November 12, 2012, after which she convened another meeting of the Foster Care Evaluation Panel headed by her on December 6, 2012. Here at long last a decision was taken to seek revocation of the foster care order and in February 2013, Udara nearly an adult, was handed over to the care of his paternal relatives. (He turned 21 on May 19, 2013)

Earlier, on January 17, 2013, Udara had informed NCPA Deputy Chairperson Mrs. Kulatunge by letter about his signature being taken on some deeds by his foster uncle in July 2011. But no action had been taken. Udara had also been threatened by the person who allegedly bought his land, his aunt says.

Ms. de Silva, along with Udara, alleges that all the monies received by Udara from local and international donors since he went into the foster care of his maternal relatives were not used for his benefit. “The money has been squandered”, says Ms. de Silva.

With no hope of succour from the NCPA, Udara and his aunt then filed a complaint about the property issue at the Meetiyagoda Police in early March 2013. It was during the police investigation that they had found to their dismay that a sale of the land had occurred.

They then complained on March 25to the Criminal Investigations Department, which in turn, forwarded the file to the Fraud Bureau.

| Report on children who lack foster care

In the First Report from the Committee on Public Enterprises (COPE) presented by D.E.W. Gunasekara, Chairman, on 1/12/2011, the issue of children affected by the tsunami has been discussed.. Of 2,661 children in 10 districts, only 264 had been provided the foster parent facility, the report states, adding that the NCPA has been directed to submit a report including relevant information of the 264 children, action taken and their present position and also the names and addresses of the balance 2,397 children on the basis of the Divisional Secretariat and their present position. NCPA has failed in its duty It is clear that the NCPA has failed abysmally in its duty as “guardian” of Udara, legal sources and rights activists said, citing the Tsunami (Special Provisions) Act No. 16 of 2005. When a Foster Care Order is made, it is the duty of the Monitoring Officer appointed by the NCPA to monitor the performance and the discharge of the duties and obligations imposed upon the Foster Parent and submit a report once in every three months to the NCPA, an activist said, pointing out that in Udara’s case this does not seem to have happened. The Panel comprises the NCPA Chairperson or nominee; a nominee of the Sri Lanka College of Paediatricians; the Commissioner of Probation & Child Care Services of the relevant province or nominee; a psychologist named by the NCPA; a psychiatrist named by the NCPA; the Director of Education of the relevant province or his nominee; and the Provincial Director of Health Services or his nominee. No answers forthcoming Conceding that the protocols with regard to tsunami orphans had not been followed by NCPA officials in Udara’s case, its Chairperson Anoma Dissanayake said that when the matter was brought to her notice she acted on it immediately. Probe by Fraud Bureau Was Udara coerced into signing the deeds for the sale of his land, is what the Colombo Fraud Investigation Bureau is probing. |

Follow @timesonlinelk

comments powered by Disqus