According to the doctor

He was upset and perturbed. Even in his limited experience as an intern house officer, the injection should have had an impact.

But there was no response and getting back to his quarters for a hurried bite of lunch, he casually mentioned to his peers the coma case he was struggling with that morning.

Usually, he would have referred the medical tomes that he was wont to do when a tricky case bothered him. He just didn’t have the time and after a quick discussion with the other interns it was back to work.

Vivid recollection of events that unfolded: Dr. Siddhiarachchige Terrence Gamini Raja de Silva. Pic by M.A. Pushpa Kumara

Dr. Siddhiarachchige Terrence Gamini Raja de Silva, now 62, was the intern on-call in Ward 47 of the Colombo General Hospital when Fr. Mathew Peiris brought his wife, Eunice.

That scene is imprinted on his memory. It was January 31, 1979.

Having passed out from the Colombo Medical Faculty, Dr. Terrence was serving his year’s internship at the General Hospital. “I had completed my six months in the surgical ward under Senior Surgeon Dr. M.H.G. Siriwardene and was on the final six months in the medical ward under Senior Physician Dr. K.J. Nanayakkara,” he says, explaining that 47 was the Female Ward and 49 the Male Ward.

Detailing the hierarchy of the late 1970s, he says, the Medical Ward was headed by Dr. Nanayakkara, under whom were Senior House Officer (HO) Dr. Wickremasinghe and Intern HOs Dr. Kanthi Pinto and himself. Of the six months, the Intern HOs had to serve three in the Female Ward and the balance three in the Male Ward. He had already completed his stint in the Female Ward but as was customary was on-call for emergencies whenever his colleague was either off or at lunch. Their working hours were from 8 a.m. to 12 noon and 3 to 5 p.m.

On January 31, 1979, he was on-call during the lunch break. He was informed that there was a “bad” patient admission. When a critical patient was brought in, the Outpatients Department put a seal that the House Officer should see him/her immediately.

“We called them ‘Stamped Cases,” says Dr. Terrence, explaining that when he went to Ward 47, he saw an unconscious patient being  brought in by two priests. One was bespectacled and bearded and the other was crying.

brought in by two priests. One was bespectacled and bearded and the other was crying.

Having to take the history of the patient, it was her husband, Fr. Mathew, who spoke on her behalf as she was unconscious. The other priest, Dr. Terrence got to know later, was a close relative.

The history indicated that the patient had returned from England in December 1978. Subsequently she began complaining of body pains, excessive thirst and loss of appetite. She was also depressed and had been treated by a Psychiatrist. The patient had felt giddy two-three hours after meals and was under the care of a General Practitioner. She had developed slurring of speech and been in and out of consciousness since 6 p.m., the day before admission.

There was a letter from the GP advising hospitalization but, says Dr. Terrence, the patient was brought in only at noon the next day.

He then went through the medical routine of asking whether the patient had a headache, chest pain, high blood pressure, was an asthmatic or diabetic. To all, Fr. Mathew’s answer was “No”.

Categorical that she was not on any medication, Fr. Mathew had also produced the letter requesting admission by GP Lakshman  Weerasena, a photocopy of a letter from another doctor and some laboratory reports.

Weerasena, a photocopy of a letter from another doctor and some laboratory reports.

“There were certain abnormalities in the fasting blood sugar in those reports,” says Dr. Terrence, pointing out that in those days while taking into consideration those results, the tests would be repeated at the General Hospital labs.

Showing Dr. Terrence a glucose tolerance test done two days before, Fr. Mathew had attempted to tell him that “glucose was bad” for his wife. When asked whether she had been taking anti-diabetic drugs, the answer had been negative.

Dr. Terrence’s examination of Eunice indicated that she was in a deep coma and was not even responding to pain. There were no external injuries. There was a needle puncture on her right hand, he recalls, adding that he put it down to blood being drawn for the tests carried out earlier.

The detailed notes of Dr. de Silva

The vital signs were not good – her pressure was a very low 60/40 and her pulse could only be “just felt” and the rate could not be recorded. “She was in a state of collapse,” he says.

After meticulous notes on the Bed-Head Ticket (BHT) on the case history and his findings during the clinical examination, the young intern gave his tentative diagnosis –‘Hypoglycaemic coma due to low blood sugar levels’. For, the reports of the blood test he carried out would come only several hours later.

He expected his treatment in the form of the administration of 50cc of 50% dextrose, along with hydrocortisone and a dextrose drip to revive the patient. “Usually, in the case of hypoglycaemia, they get up and walk after the injection,” he says, but this patient didn’t regain consciousness.

He was troubled, caught up in a storm of doubts whether his diagnosis was wrong or the patient had permanent brain damage.

His mind goes back to that day………“I always carried two pens, a blue and a red, with me. The case history I would write in blue on the BHT and at the end in red would be the diagnosis.”

Clear as crystal it seems to be even to this day, 34 long years later. Hypoglycaemic coma, he wrote, followed by a small arrow, pancreatic tumour, another arrow and then overdose of hypoglycaemic agents and another arrow.

‘Poisoning’, was the word that followed the final arrow.

What Dr. Terrence didn’t realise at that time was that the BHT would become part of the incriminating evidence against Fr. Mathew who would later be convicted of murder by the High Court.

As his second diagnosis, he jotted down cerebro-vascular accident (stroke), for the patient was a 59-year-old woman. Later that day, his “tentative” dignosis of hypoglycaemic coma would be confirmed by the lab reports.

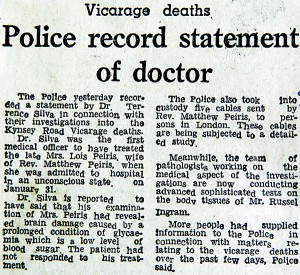

The ‘police message’ calling Dr. de Silva for the investigation

With no signs of recovery, Dr. Terrence did inform Fr. Mathew that the patient’s condition was poor. The reaction was “neither happy nor sad”, with the only question being, “Will she die?”

When he queried why Fr. Mathew was asking him that, he had told him that he wished to inform their children.

He relives that day once again. After the initial treatment, as the phone in the ward was not working, he rushed to the telephone exchange to make a call to his Consultant or SHO about the ‘bad’ patient. “Those were the days we had no mobile phones,” he says, adding that the crush around the telephone exchange was huge. Many interns were attempting to contact their senior doctors.

He, however, knew that his seniors would be in the ward at 2.50 p.m. sharp and so decided to snatch some food and get back soon.

Concerned that he may have done the wrong thing by giving dextrose, he ran it past his peers at lunch who affirmed the treatment.

It was then that a casual reference came about a similar case several months before, that patient too being brought by a priest. The person (later to be identified as Russel Ingram, husband of Delrene, the lover of Fr. Mathew) had died, and suspecting that it may have been due to an insulin-secreting tumour, a post-mortem had been performed but no tumour had been found.

Immediately seeing the light, Dr. Terrence had got back to the ward and told not only Dr. Kanthi but also the SHO, with events occurring quickly thereafter. It was high drama at the General Hospital — an entry on the BHT, onto the Police Post and no one, other than medical and nursing staff, being allowed at the bedside of the patient.

The irony is that Eunice Peiris was in Ward 47 for 47 days before her death, says Dr. Terrence, a Specialist in Community Medicine who later went onto head the General Hospital and see its transformation into the National Hospital of Sri Lanka and rose to be Deputy Director-General of Medical Services at the Department of Health Services. Now he is retired. Dr. Kanthi Pinto is a Consultant Paediatrician attached to the Ragama Medical Faculty of the Kelaniya University.

Dr. Terrence, the young intern who saw Eunice and was instrumental in changing the course of events, unlike in the case of Russel Ingram, would spend many a day in court giving evidence.

The rest, of course, is history. The Vicarage double murders are back in the public domain many decades later, lifted from the dusty court records and newspaper archives, to the big screen by reputed film-maker Chandran Rutnam.

Follow @timesonlinelk

comments powered by Disqus