Life in the beloved ‘Bloc’

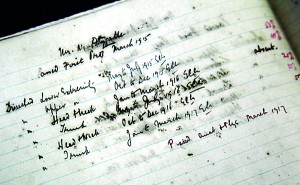

The entries in the book are meticulous as well as handwritten beautifully.

A random page reveals………“Dissected lower extremity, dissected upper extremity, dissected head & neck, dissected trunk.”

This entry in a ledger 100 years old just like the building it’s being kept at, interestingly records the passage of none other than Sir Nicholas Attygalle, eminent Academic, Surgeon and Senator, through what medical students call their beloved ‘Bloc’.

With a page for each and every medical student who passed through its portals then, the one for ‘Mr. N. Attygalle’ states clearly, “Passed anat & phys March 1917”.

Anatomy building: The place where new medical students meet en masse for the first time. Pix by M.A. Pushpa Kumara

Although the record-keeping has changed over the years and the ledger is now history, the Anatomy Bloc which has already begun its centenary celebrations, ahead of its anniversary on November 3 (2013), remains the very heart of the Colombo Medical Faculty.

The Bloc stands apart on Francis Road, behind the cluster of buildings which forms the Medical Faculty.

It is one of only two old buildings, though renovated to overcome the onslaught of the weather, but keeping the façade intact. The other is the Koch Memorial Clock Tower, built in memory of the Medical School’s second Principal, Dr. E.L. Koch in 1881. The Medical Faculty had its beginnings in 1870 and is believed to be the second oldest in South Asia, after the Bengal Medical College, India.

The Bloc as the anatomy building is fondly called is where new medical students meet en masse for the first time, the Dean of the Colombo Medical Faculty, Prof. Rohan Jayasekara who is also Senior Professor of Anatomy tells the Sunday Times, while Ordinary and Advanced Level students are led on a journey through the human body elsewhere in the same building.

Writings from the past: A page for each student

Speculating why it is referred to as the ‘Bloc’, Prof. Jayasekara says the first hurdle or block the students have to overcome is the 2nd MBBS examination.

“You are given only four attempts, after which you have to leave medical school,” says Prof. Jayasekara who has seen many a medical giant pass through.

The events associated with the anatomy building were many, the Sunday Times learns, with Bloc concerts and ‘Bloc Nites’ with ‘Bloc Queens’ every year.

Earlier the building was known as ‘Block’ and the festivities as ‘Block Night’ but over the years it had changed into the shorter versions.

Bloc life is unique, according to him, with all new entrants to the Medical Faculty whatever strata, economic, social or religious background, coming together as one. Walking into the Bloc as individuals, within its fold, they would move and mix as one undisturbed batch, in the olden days for five terms (1½ years) and now under the new curriculum for three.

Once they get past the 2nd MBBS “block”, leaving the Bloc behind, they would be divided into clinical groups, with the batch concept being there only at lectures.

The culture of the Bloc is that the students in small groups of 4-6 are allocated a body or cadaver, after which they would become a “family unit”.

Prof. Rohan Jayasekara

Here in this historic building young men and women aspiring to be doctors get a “close look” at both the inside and the outside of the human body.

Within their own group, some would dissect the body, others would read from the texts, in a division of labour, laughs Prof. Jayasekara, while still others would snore. On Friday the dissections would be completed, followed by an oral test on Monday. Some students would keep their eyes glued to the body but others would just put their nose in only on Friday.

Most of the top surgeons would have got a flavour here of the work they would do later, he says, adding that in those days there would be no gloves, but bare hands would be used.

For many, the Bloc is characterised not by the stench or the smell but the “odour” of a mixture of formalin, glycerine and preservative fluid, says Prof. Jayasekara. This odour would be persistent even when the students boarded buses or trains to get back home, drawing looks of disgust. Now, however, there is no odour.

There were also the pranks, the Sunday Times understands. After boarding a bus, when pretty medical students dipped their hands into the bags to get the coins for their fare, their fingers would come across a part of the human body, surreptitiously put in there by the lads. There would be no bounds to the wrath of the girls the next day, when they met their batch-mates.

Some of them would also be told to check out a cadaver and on pulling off the covering would yell out a terrified scream when it sat up. A medico substituted for the cadaver!

The pranks are no more and before the cadavers are brought before their eyes, they are not only given an orientation but also a pep talk on how to respect the bodies by the Head of the Department of Anatomy and Consultant Eye Surgeon, Dr. Madhuwanthi Dissanayake. Now religious ceremonies are held annually in thanksgiving to those who have donated their bodies and also their relatives.

Dr. Dissanayake believes that around 143 batches would have passed through the hallowed halls of the Bloc, since it was opened by Governor Robert Chalmers. They learn the bare bones of medicine–the structure of the human body at the Bloc.

As a cadaver is kept on the table and students gather round, it may come as a psychological shock, she concedes, but hastens to add that it prepares a medical student to face any situation. From this year, there are group leaders who will be the ‘Body Father’ and ‘Body

Dr. Madhuwanthi Dissanayake

Mother’ to take good care of the cadaver.

Meanwhile, stressing that the Bloc is “100 years young”, Prof. Jayasekara says that when thinking of the centenary celebrations they wanted to engage in “institutional social responsibility” and through the exhibition entice students to take to the study of human biology and medicine.

As the Bloc is on the threshold of the next 100 years, Prof. Jayasekara and his team hope to strengthen the research aspects of regenerative medicine.

Follow @timesonlinelk

comments powered by Disqus