One foot in the past

“All men, whatever their condition, who have done anything of merit,” wrote Benvenuto Cellini (1500-1571),“if they be men of truth and good repute, should write the tale of their life with their own hand.” Very few practising architects have taken the advice of this Renaissance artist and autobiographies by architects are very rare, especially by those who practised the profession in Sri Lanka. Therefore, ‘IN SITU’ probably is the only one of its kind.

Plesner at his office at Edwards Reid and Begg

The title of this memoir, ‘IN SITU’, which Ulrik Plesner has aptly chosen was a current and popular phrase among architects, engineers and contractors in the 1950s and 1960s and describes the years he was in Sri Lanka. The etymology of the phrase dating to 1740 is defined in the Oxford English Dictionary as ‘in its original place’ or ‘in position’.

Often, memoirs and autobiographies are written for various personal and public reasons but this book seems to have been written by Plesner to re-affirm the role played by him as an architect in those eventful years in Sri Lanka. In a narrative written simply in unhurried style, Plesner sets out six significant aspects and contributions he has made:

* His collaboration with Geoffrey Bawa, which proved crucial to the building projects, carried out jointly at the firm Edwards Reid & Begg architects, between 1958 and 1967.

* In introducing with Bawa, an approach to architectural design of domestic buildings that was undeniably new to this country. Traditional design elements associated with monsoon South Asia such as internal courtyards, roofs with wide eaves, colonnaded verandas, trellis windows, platforms and masonry furniture, murals on walls were integrated and adapted to architectural designs.

* Collaborating with artists and sculptors to form an integrated solution for his buildings, with an example of such a successful joint effort being Plesner’s suggestion to Australian painter Donald Friend to create sculptural forms in a utility material like aluminium.

* The documentation of ancient buildings of Sri Lanka’s rich building heritage, thereby highlighting its relevance to contemporary building techniques. By re-identifying the vernacular, Plesner injected a whole younger generation of designers with his enthusiasm and passion.

* A novel and practical approach to teaching design at the School of Architecture at Katubedde, established in 1960.

* The overall planning of the townships of the Mahaweli Irrigation Project, which as its Director he designed and built with consummate dedication, passion and skill (1980-1987).

The book, however, offers much more than a mere defence of his contribution to Sri Lankan architecture. Plesner’s narrative transports the reader to five separate countries, where he grew up, laboured and lived – Scotland, Denmark, Sri Lanka, England and Israel. As the sub-title of the book makes eminently clear it is primarily an architectural memoir focusing on Sri Lanka, opening with events here, and not unlike a symphony, ending here as well. His narrative, recorded half a century later, chronicles events and personalities he encountered from 1957 to 1967 and again when he returned in 1980-87.

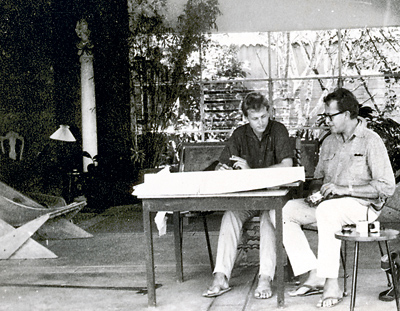

At work: Plesner and Bawa

Whole pages, almost a quarter of the book, are literally “plastered “ with rare and extraordinarily evocative, stunning, black and white images of buildings — some under construction and others complete with exquisite interiors, landscapes, portraits of people and personalities. Some have never been seen before by the public. Designs of buildings with layout plans, and other drawings support the text.

The images are by Plesner and eminent cameraman Nihal Fernando. According to the blurb, “the photographs were taken over 50 years ago and most of the buildings have been so changed by life they cannot be re-photographed”.

The book offers an account of Plesner’s life. Born in Florence, Italy, in 1930, he had an idyllic childhood, later moving to Scotland and Denmark, growing up in a cosmopolitan European milieu, surrounded by family and friends, many of whom were renowned artists and architects.

Plesner was from a distinguished family of architects, with his grand-uncle also named Ulrik Plesner and his stepfather Karre Klint being well-recognized members of the profession. Klint is best known in Denmark as the architect of the arresting and monumental Grundvig’s church (Copenhagen, completed 1940).

In Denmark, Klint is a household name in furniture and synonymous with modern light fittings. Young Plesner studied at the elite architecture school, the Royal Danish Academy (RDA), founded in 1741, Copenhagen, where solid, functional teaching and training techniques were combined with the best building traditions of the Danish welfare society.

The RDA offered more than most architecture schools to those learning the craft of building. A majority of students who enrolled here were skilled enough to be professional carpenters, while others excelled as bricklayers or plumbers. Plesner took to working at a construction site during the four-month summer vacation in 1949-50 and the skills he acquired contributed to making him pay attention to detail, which Plesner believed was the bedrock of good functional architecture.

He also worked part-time at the National Museum, Copenhagen, on a project documenting old castles and grand residences, which further honed his appreciation and respect for traditional buildings and techniques. While most of his contemporaries in the RDA from where he graduated in 1955, went in search of careers to Scandinavia, Plesner looked East. Delving into Buddhist philosophy may have propelled him to take part in an architectural competition mooted by the Prime Minister of India, Jawaharlal Nehru (1947-1964) and the Lalith Kala Academy in New Delhi to commemorate 2,500 years of the founding of Buddhism. His unique shell-domed entry earned him third place and whetted his appetite to journey to the sub-continent.

Plesner with his antique Fiat in Kandy

The next decade, 1958-67, proved crucial for him as well as Sri Lanka. The post-independence decade prior to Plesner’s arrival saw the influx of a dozen or more architects trained in England who sought to qualify as members of the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA).

Post-independence Sri Lanka, with its multi-cultural heritage faced a host of problems, which were entrenched in the economic, political and social structure. But independence offered the opportunity for Sri Lanka to choose its own destiny and identity after enduring four centuries of European rule, which although had had a withering impact on the development of the traditional crafts, had also added another layer of cultural heritage.

The newly-emerging middle class, shackled with an education and upbringing largely based on European ideals and norms, found Sri Lanka to be alien. They could be aptly described in the words of Macaulay (although the comment referred to Indians): “A class of persons Indian in blood and colour but English in tastes, opinions, morals and intellect.”

This in essence was the architectural landscape in which Plesner found himself in, when he stepped off the Italian liner M/Victoria in Colombo harbour in January 1957 to be greeted by architect Minette de Silva in an open boat which ferried him back to the terminal. Colombo in the late 1950s was a backwater, where serious cultural events were few.

After a fruitful year working with Minette de Silva, he linked up with Geoffrey Bawa in 1958, another of those architects who had returned from England. Working alongside two of the most influential architects of post-independence Sri Lanka gave Plesner an extraordinary window of opportunity to widen his horizons.

As Plesner must have been aware during his years of growing up in Europe, the 20th century was the Golden Age of the Masters of modern architecture and the plastic arts, led by the experimental works of Wright, Le Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe and Walter Gropius. They issued lengthy personal manifestos on architectural design, enthusiastically supported in print by their unquestioning acolytes.

Plesner was guarded and wary of the architectural press and media’s uncritical praise extolling the virtues of the new architecture and the work of great architects for their own sake.

In the course of his travels, even though he came face to face with the work of major architects, more often than not he found them monumental, sterile and lacking charm. It made him despondent. Several of the icons and idols of modern architecture on the high altar have been trashed and severely castigated in his book. His trenchant criticism of the works and designs (built and unbuilt) by Le Corbusier (at Chandigarh), Louis Khan (Tel Aviv) and Arne Jacobsen (Islamabad) makes depressing but fascinating reading.

It is remarkable and almost inconceivable that when Jorn Utzon, one of the leading architects of the 20th century, won the worldwide design competition for the Sydney Opera House and offered Plesner the post of project supervisor in 1957, he turned it down. His previous experience of designing shell structures and their limitations had taught him to be circumspect. Plesner had adverse and critical comments to make on Utzon’s approach to the understanding of shell structures and believed that this was the single fundamental issue that hindered the progress of construction of the Opera House and triggered an ever-soaring cost culminating in Utzon abandoning the work.

The major lacuna and omission in the narrative, however, are the source of Plesner’s inspiration. Did no architect influence his work? Or was it that he sourced his ideal models synthesized from the natural environment or the historic man-made environment like ancient buildings?

Elsewhere in tropical countries of the old as well as the new world, attempts were being made to come to terms with building solutions incorporating ecological, cultural and social elements that were similar to ours. The buildings (in the late 1940s and early 50s) of Mexican architect Louis Barragan who often cited Le Corbusier as one of his main sources of inspiration were eye-openers to us all who worked at Bawa’s and Plesner’s office.

Barragan was an influential and inspirational source for the work of Sri Lankan architects of the 1960s and 70s. Several design elements such as masonry seats, tables, beds, built-up ponds and pools, large oversized concrete walls, pergolas and other details echo in the collaborative work of Plesner and Bawa. Did Barragan’s design solutions impact on their work?

Interestingly, an architectural landmark, the Baur’s Flats and Office Complex, Fort, built in 1941, was recognized as one of the radical designs in the South Asian region. The apartments with their unique double height living spaces and great wealth of detail were a source of inspiration to a generation of architects from the 1960s. Plesner who was well acquainted with the Baur’s building complex, resided there in 1958 and also undertook an office restoration project in 1960.

The spatial manipulation of the living spaces are echoed in three houses Plesner designed for Barbara Sansoni’s annexe and the residences of Ian and Gun Peiris and Maurice and Malkanthi Perera. Were these ideas borrowed or redefined? Or have they no connection at all? These are some of the intriguing questions that need to be answered both by Plesner and others who are engaged in debates on the Sri Lankan architectural style.

Follow @timesonlinelk

comments powered by Disqus