Come, see the unseen

April 4, 1977. Stefan D’Silva still remembers the day he left Sri Lanka aged 21 for what he imagined to be greener pastures. Time and experience has made him a wiser man, though. “I might have migrated” he says. “But my heart never left.” Thirty six years later the photographer spends more time in his native land than in his adopted country itself and soon hopes to move back to Sri Lanka to take up permanent residence. In the meantime he has launched a third photo journal about the country with childhood friend Ali Mohideen. ‘Places Once Denied’ is a chronicle of their travels across “what is essentially the LTTE map”, a visual homage to the places that they were finally able to access with the end of a war.

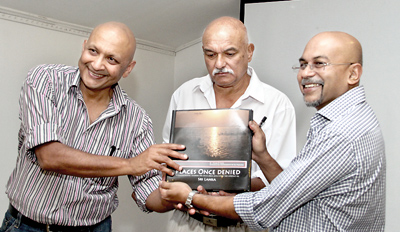

Stefan D’Silva and Ali Mohideen launching their book at Gandhara-- presenting the first copy to Dian Gomes (right). Pic by Indika Handuwala

The idea for the book came to Stefan in 2010, just after the end of the war. “For 30 years we’ve been dreaming of visiting these places-these beautiful villages and cities we couldn’t access because of the war.” It just goes to prove that the heart always wants what it can’t have,” he smiles, saying that both he and Ali were on a plane to Sri Lanka as soon as they figured out that these elusive sites were now open for exploration.

There was more to it than just aesthetics though. “My purpose in publishing this is to go some way in dispelling all these vicious rumours that are being circulated among the Sri Lankan diaspora right now,” he says. “The rubbish being published online-most of it by keyboard researchers-is atrocious. I want to encourage people to come and see for themselves-photographs often go a long way in convincing them to do just that.”

Perhaps the best advice they received in this task was from one local they met on their travels. Don’t take pictures of the war memorials, he said-take pictures of the people and places. That put things in perspective for the two photographers. “He was right-it’s the same bullet hole, the same wall. What’s more important is what’s behind that wall. How are people getting on? That was our question.”

For this purpose there’s a lot to be said for village life and minding other people’s business, Stefan laughs. “You will learn more sitting at a roadside kade sipping a kopi than you ever will in a lifetime of reading about it,” he points out. “You travel to Jaffna and you see the huge number of Buddhists there-you have to wonder, if things were that bad how are they still living with each other over there?” By no means is he implying that things are all rosy, but neither is it all doom and gloom, he says. “There is this expectation for Sri Lanka that it should develop overnight but that’s just not fair. It will take time.”

Two contrasting worlds: An old church and new bridge |

|

If there was one thing that was apparent to the photographers during their travels it was the slow acceptance of change in those regions. “There is this sense of resentment among the older generations about the rapid change happening in those areas. They’re finding it difficult to deal with it. But you do see the younger generation embracing it with a lot of enthusiasm. We photographed a lot of girls on scooters, guys messing with their mobile phones. Change is happening-it’s slow, but it’s there.”

Both Stefan and Ali are wildlife photography enthusiasts so they were thrilled to gain access to areas like Wilpattu. Between them the two covered some 7000 miles in a mere six trips. It was an exercise in faith, smiles Stephan. Assisted by companion Ananda Welikala they would navigate through the North-Western, Northern and Eastern belt, finding their way more through conversation with locals than with maps. Stefan was asked quite frequently how he managed to get past the checkpoints, mainly because of his fair skin. He will tell you that not once was he harassed. “It’s all about showing a bit of courtesy. Let’s face it-the guy who’s been standing in the sun for twelve hours is not going to act with the grace of an airhostess.” They were both pleasantly surprised at the smooth sailing all through. “I was walking by myself alone at night in Jaffna during the Nallur festival,” Stefan remembers. “Absolutely nothing happened.”

He also remembers being stunned during their trip to Batticaloa. “The last time we went, Batticaloa was one big jungle with a dirt strip running through it. Now it’s got four lane highways, palm trees and some great schools.” And everywhere they went were tourists.

As for his fellow countrymen who find themselves hopping on a plane to Singapore for shopping but won’t travel up North because it’s ‘too far’, Stefan has two words. “Go now.” There is too much that is beautiful to not be seen by everyone, he smiles. “Chundikulam with its picturesque lagoons, Wellawaya with its centuries of history and Pottuvil with its amazing religious monuments are sights you must take in during this lifetime. Did you know that you can now walk across these old battlefields in Sri Lankan history? Can you imagine doing that with a metal detector? Imagine the centuries of history yet to be discovered. The potential is tremendous.”

“It’s important that people from the cities see these people and they see us,” he points out. “There’s such a disconnect between Colombo and the rest of the country.” The chasm is so wide that we’ve almost become mythical creatures to each other,” he laments. If things are to improve, the new generation will have to take up the call. “I’m in the departure lounge now,” he laughs. “It’s up to the next generation to figure out how Sri Lanka will modernise while keeping our shared identity.”

Stefan hopes that this photo journal will go some way towards encouraging people to embrace their cultural heritage and everything that is beautiful about their island. “Every time you probe something in this country it’s like opening Pandora’s Box. It defies stereotypes.” Acceptance is important after all, warts and all. “You just have to love Sri Lanka for all its imperfections.”

comments powered by Disqus