Minister, please help our doctors qualify younger

| Report prepared by a research team comprising Prof. Chula Goonasekera, Prof. M.H. R Sheriff, Dr. P.M. Amarakoon, Dr. T.A. Arapola, Dr. A.A.N. Dharmarathne, Dr. M.S.F. Silmiya, Mahes Salgado and Dr. K. Pethiyagoda of the Universities of Peradeniya and Colombo |

Approximately 1000 medical graduates qualify annually from the six, long-established state-run medical schools in Sri Lanka but a comprehensive review of their performance (so far) has not been done. We feel this is a must and duty as our medical education is totally funded by the public taxpayer.

In general, our undergraduate medical education compulsorily commences soon after the Advanced Level qualification. The  late entrants have no opportunities in Sri Lanka as there are no schemes for graduate entry to medical schools. The commitment for postgraduate (PG) study to the contrary is voluntary and its timing is entirely personal.

late entrants have no opportunities in Sri Lanka as there are no schemes for graduate entry to medical schools. The commitment for postgraduate (PG) study to the contrary is voluntary and its timing is entirely personal.

Thus, self motivation plays a major role in triggering post graduate medical education in our country. Therefore, the learning received in the medical schools, in terms of quality of teaching, learning methodology, educational environment, career guidance counselling, role modelling and its hidden curricula and personal factors play an important role upon subsequent self motivation of students to pursue postgraduate medical education. Therefore, to some extent, medical schools are responsible if their graduates were to perform differently as postgraduates. Such differences in performance will also carry a strong argument for the state to review less performing schools and consider additional support, funding, staffing or even closure.

In Sri Lanka, postgraduate clinical education of medical graduates is unique, as it is conducted only by one institution, i.e. the Postgraduate Institute of Medicine (PGIM) established by an Act of Parliament in 1976, affiliated to the University of  Colombo. The Colleges, Faculties, Societies and Academic Departments with specialty interests contribute to curriculum development; training and examinations through the respective Boards of Studies of the PGIM empowered to confer the respective postgraduate degrees. A medical graduate qualifying in Sri Lanka becomes eligible to enter any qualifying examination of postgraduate education of his or her choice at the completion of one year of clinical training subsequent to full registration at the Sri Lanka Medical Council. The latter is available only for graduates who have successfully completed the one year of internship.

Colombo. The Colleges, Faculties, Societies and Academic Departments with specialty interests contribute to curriculum development; training and examinations through the respective Boards of Studies of the PGIM empowered to confer the respective postgraduate degrees. A medical graduate qualifying in Sri Lanka becomes eligible to enter any qualifying examination of postgraduate education of his or her choice at the completion of one year of clinical training subsequent to full registration at the Sri Lanka Medical Council. The latter is available only for graduates who have successfully completed the one year of internship.

Since the government has adopted a policy of recognizing qualifications offered by the PGIM over and above that of other equivalent qualifications obtained elsewhere and the Ministry of Health, the biggest employer of doctors in the country recognizes PGIM qualifications as essential to gain specialist status or promotions, most Sri Lankan doctors have opted to obtain their postgraduate competencies via the PGIM. We report postgraduate academic performance with reference to the medical school on all qualifying postgraduates of the PGIM over a 7-year period.

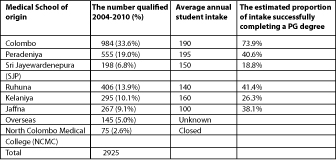

Between January 2004 and December 2010, a total of 2925 medical graduates successfully completed a postgraduate degree of the PGIM. Of these, 2780 (95% had obtained their primary medical degree from a Sri Lankan medical school. However, when the adjustment for average annual intake of undergraduates to each medical school was considered, the estimated proportion of students successfully completing postgraduate examinations from each medical school were remarkably different.

of the PGIM. Of these, 2780 (95% had obtained their primary medical degree from a Sri Lankan medical school. However, when the adjustment for average annual intake of undergraduates to each medical school was considered, the estimated proportion of students successfully completing postgraduate examinations from each medical school were remarkably different.

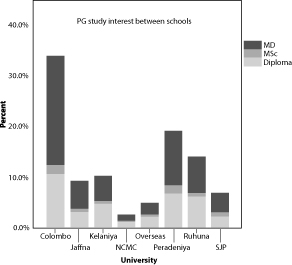

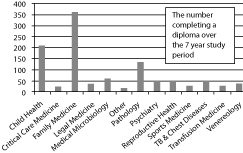

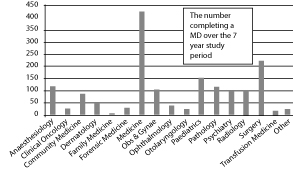

Of the 2925 medical graduates, 1650 (56.4%) obtained a specialist degree MD, 202 (6.9%) an MSc and 1073 (36.9% a diploma.

From among the study programmes offered by the PGIM, Medicine and Surgery seems to be the most popular choice amongst the MD graduates whereas Family Medicine and Child Health were the specialities amongst diploma candidates.

The admission of students to all state run medical schools was annually based on the Advanced Level examination merit (40%), with a proportional adjustment to districts to compensate for discrepancies in living standards and educational  facilities (60%). Since there has been a great demand for medical school entry, over the years, only the best performing students usually scoring a Z score of 2.0 or above were selected to study medicine. A proportion of students who were selected on a district basis may have had a lower Z-score, but were the best performers in their own districts. Thus, it was prudent to assume that the medical student population of Sri Lanka belonged to the top 5% performers in the Advanced Level examination. Therefore, the quality and potential of students can be considered uniform. They all followed the MBBS course of study in English medium for five years. All state medical schools were annually allocated an equal amount of recurrent funding by the University Grants Commission, on a per student basis and hence the availability of finances between schools was comparable.

facilities (60%). Since there has been a great demand for medical school entry, over the years, only the best performing students usually scoring a Z score of 2.0 or above were selected to study medicine. A proportion of students who were selected on a district basis may have had a lower Z-score, but were the best performers in their own districts. Thus, it was prudent to assume that the medical student population of Sri Lanka belonged to the top 5% performers in the Advanced Level examination. Therefore, the quality and potential of students can be considered uniform. They all followed the MBBS course of study in English medium for five years. All state medical schools were annually allocated an equal amount of recurrent funding by the University Grants Commission, on a per student basis and hence the availability of finances between schools was comparable.

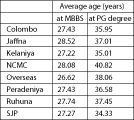

Despite the above, the average age of obtaining MBBS and PG qualification and the student interest in pursuing a MD,  Diploma or MSc program and the durations required following the MBBS to successfully complete a postgraduate degree was different between graduates of different medical schools.

Diploma or MSc program and the durations required following the MBBS to successfully complete a postgraduate degree was different between graduates of different medical schools.

Since the NCMC was closed in 1989 and the overseas category was small (5%), we are unable to comment on their performance as the data is biased. The first batch of students of the Faculty of Medicine, University of Kelaniya completed their first five-year course and graduated with the MBBS degree in 1996. Since our postgraduates on average have taken 8 years for completion of a postgraduate degree, it is likely that the data represented here in this study may have slightly disadvantaged Kelaniya medical school and may partly explain the reason for a lower proportion of undergraduates committing for postgraduate studies from Kelaniya. This is because Kelaniya had no senior alumni who would have entered the postgraduate training programs and qualified within our study period as seen in other medical schools.

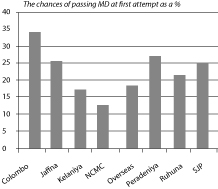

We also found that the preferences of the graduates to obtain an MD, or M Sc or Diploma was also significantly influenced by the medical school of origin. Whilst, over 2/3rd of the graduates from Colombo have completed a postgraduate degree, only 2/5 students from Peradeniya, Jaffna and Ruhuna faced the challenge. The lowest performers were Kelaniya and SJP and only 1/5 of their graduates successfully concluded a postgraduate degree. What is surprising is that the best (Colombo) and the lowest performing medical schools (SJP & Kelaniya) in this respect were situated within a 5-mile radius in the capital city of Colombo.

We also found that the preferences of the graduates to obtain an MD, or M Sc or Diploma was also significantly influenced by the medical school of origin. Whilst, over 2/3rd of the graduates from Colombo have completed a postgraduate degree, only 2/5 students from Peradeniya, Jaffna and Ruhuna faced the challenge. The lowest performers were Kelaniya and SJP and only 1/5 of their graduates successfully concluded a postgraduate degree. What is surprising is that the best (Colombo) and the lowest performing medical schools (SJP & Kelaniya) in this respect were situated within a 5-mile radius in the capital city of Colombo.

Thus, their awareness of resources available and accessibility for postgraduate education could be considered equal. It is known that medical students portray distinct patterns of autonomous and controlled motivation that seem to relate to the learners’ frame of mind towards learning as well as the educational environment. Autonomous motivation has closer relationships than controlled motivation with measures of self-regulation of learning and academic success in the context of a demanding medical programme.

Therefore, the vast difference for postgraduate commitment seen amongst our group of students should be related to their attitudes and motivation inculcated during their undergraduate years of education. Despite many transport and access problems that were prevailing at the time (2004 2010) due to terrorist activities affecting the North and East, the medical undergraduates from Jaffna have managed to stay on par with their colleagues from Peradeniya and Galle affirming the observation made earlier, i.e. the attitudes and motivation instilled in students while in the medical school do in fact influence the commitment for postgraduate education and performance.

There is evidence that the place of medical school training is also an important factor in determining success in postgraduate examinations. For example, the performances of candidates in the MRC Psych examinations abroad were closely related to the age at which the examination was attempted. They found that those who passed the Part II examination were significantly younger than those who failed (mean 32.0 years v. 34.8 years) and had qualified for a significantly shorter period of time (mean 7.3 years v. 9.4 years). In this context, our graduates were significantly older (38 years) and this would have contributed to lesser chances for success.

Although the students at entry to each medical school should have been of the same age group, a small but statistically significant difference was noted of their age at undergraduate and postgraduate qualification. Males and females seem to perform equally well. However, most seem to obtain their postgraduate qualifications between the ages of 35-40. This is a matter of serious concern as in general, most medical postgraduates around the world would complete degrees at a relatively younger age 30-32. This is not cost-effective for Sri Lanka as delayed qualification results in a shorter duration of subsequent service at specialised level before retirement.

There is a need to close this gap by eliminating unnecessary delays in university admissions, and the substantial period of uanemployment (approximately 1 year) before recruitment as intern medical officers to the Ministry of Health following an MBBS qualification. This will allow young doctors complete their internships early and commit themselves for postgraduate study. On the other hand, the Postgraduate Institute of Medicine should also seriously consider doing away with the mandatory requirement of 1-year clinical service to enter a qualifying examination of the PGIM, after completion of 1 year internship and obtaining full registration at the Sri Lanka Medical Council, a requirement hitherto not observed elsewhere in the globe. This pre-requisite has no justifiable basis in the world of medical education moving towards specialisation and sub-specialisation.

The effect of age on examination success is well known. The strongest factors predicting successful results in, for example, Foreign Medical Graduate Examination in the Medical Sciences were age of taking the examination below 30 years of age.

The mean age at which the 1st degree (MBBS) was obtained between medical schools was significantly different i.e. was higher in those graduated from Jaffna and lower in those graduated from Sri Jayewardenepura (SJP). This should be related to delays unique to each medical school that needs re-address at local level. This could have resulted from non-concurrent dates of admission to each medical school and variable delays that had occurred within the study programme due to unexpected obstacles (unrest, industrial actions), outdated design, inefficiency and political reasons.

Despite MD programmes of training being relatively longer (6-8 years), graduates of all schools completed MD qualifications at a relatively younger age compared with their counterparts who opted to do M Sc or Diploma degrees of lesser duration (2-3 years). This suggests that students entering MSc and Diploma programmes did so relatively late in life. This also reflects an underlying difference in attitude amongst the students committing to undertake a relatively short and easier programmes of study.

We found in this cohort that at best only 1:3 candidates obtained their postgraduate qualifications at the first attempt. This suggested that most graduates did not complete their required learning curves before sitting the examination for the first time despite being in the course for a relatively long duration. In this context, the PGIM and Colleges should re- evaluate their initiatives to provide necessary facilities, opportunity, material (courses, workshops) and assistance (tutors) to complete their learning curves before appearing for the examinations for the first time.

Furthermore, the mean time duration between 1st degree and the postgraduate degree was also significantly influenced by the medical school of origin. This observation too supports the notion that attitudes and capabilities of self-motivation and self-study inculcated in the medical school do indeed matter in postgraduate education. This may also be linked to social networks of friendships and ethnicity at medical school that influence learning hitherto not studied in Sri Lanka.

The differences noted above should not only prompt Sri Lankan medical schools to re- address their education strategies but also alert the government to undertake urgent measures to minimize prevailing obstacles for postgraduate medical education and ensure that Sri Lankan medical graduates too are provided with the opportunity to qualify at a younger age to serve the best interests of the country.

comments powered by Disqus