Keyt’s sketches to a daughter

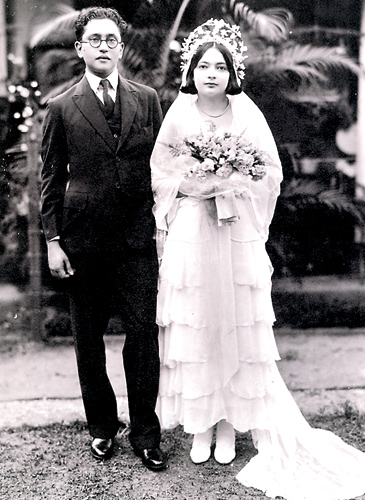

My parents, George Keyt and Ruth Jansz, married at St Mary’s Church, Kurunegala in 1930. I was born in September 1935. When I was five months old my mother went back to teaching at Trinity College. My mother’s income had freed my father from the drudgery of working at meaningless jobs and so he devoted himself to painting. When I was born my father delighted in this new little person, playing and creating stories and pictures to amuse me. As I started to babble and then to talk, he put down these pictures and rhymes in a book.

Mummy spent her spare time reading and singing to me in the nursery. She was a born teacher and loved to teach me my letters and numbers. By the time I was two I could recognise all the letters in the English alphabet. I was the darling of the household. My grandmother, Constance Sproule and my aunt, Peggy Keyt doted on me.

My grandmother (Nana) took me to a nursery school run by a Welshwoman who we called Aunty Taffy. On my first day she tested me with some cards with pictures of objects and their initial sounds. I was fine with “duh for dog” and “luh for lion” but when we came to “tuh for tap” I came out with “tuh for pipe.” Aunty Taffy was sad.

Father and daughter: George and Diana

“This is what comes of learning nouns from the servants,” she said. Of course she knew that the faucet or tap was called PIPE by the Sinhalese. Anyway, she went forward to teach me reading. The bad part of Aunty Taffy’s school was break time. I was forced to drink milk mixed with cocoa from an old glass medicine bottle, which had a stopper of a slimy cork. The nasty milk would make me gag and sometimes vomit but I had to drink it because I was told milk was so good for one. Eventually Aunty Taffy could stand it no longer and told my Nana, when she came to take me home, not to send any more milk to her school.

Peggy and Ruth, the two family wage earners, were away during much of the day. My companions were my Daddy and my Nana.

Nana kept guinea fowls. In the morning, before the sun was up, she called them, “Chick, chick”. At the sound, I came running up to her. So she created her special grandmother name for me “Chickie”. Daily, before she did anything else, she scattered food for her hens outside their little house. They had black, white- speckled plumage and their voices were a sort of whistling wheeze. They spread out into the garden but as night fell, they retired to their coop. While they were out on their foraging expedition, Nana took the eggs from the coop and returned to her room. At dawn, my Nana pumped up her little kerosene stove and fried herself one of her guinea fowl eggs. After playing with my Daddy, it was time to visit Nana. Another egg was fried on the stove. I gobbled the delicious runny snack, and then my ayah dressed me for the day while Nana put on her complicated clothing. I ran back to her and it was time for our daily walk.

“My constitutional,” she called it. Sunny or rainy, we strolled on the lake bund before breakfast time; she in her elegant dress, Lyle stockings, sturdy black shoes, sun hat and always her “bastama” – a beautiful lacquer-work walking stick; I, neat with socks and shoes, nicely combed hair and a clean frock. With her spare hand Nana kept a firm grip on mine, for my boundless two year old energy sometimes had me running into the main road. On one such rainy day, I was feeling thirsty and showed my grandmother how much water surrounded us though we could not drink any of it. “Water, water, everywhere,…Nor any drop to drink,” she said and then went on to recite the entire Ancient Mariner. She could recite all of Coleridge and Wordsworth and pages of other English poets without any trouble at all.

Many years ago there were still in Kandy, decaying mansions of the Portuguese gentry. On one of our afternoon calling days, Nana and I went to an area of dark little narrow streets and entered a large gloomy house. We went in to visit two ancient ladies, resplendent in outdated European clothes, who spoke with my grandmother in Portuguese. It was a new experience to hear a language I did not understand. My grandmother had a natural gift for languages and spoke Tamil fluently, but I had never heard Portuguese before. These were maiden sisters of her mother, who had been a Pirez. One aunt had a pet mynah who hopped on the train of her gown for a ride as she walked from room to room. They were very slim and had grave aquiline faces with pale, olive skins. These two ladies must have been about a century old. We nibbled on food served by an even older and thinner waiting woman.

Wedding portrait: George Keyt and his bride Ruth Jansz

At Upper Lake Road visitors arrived almost every evening. Many friends were artists who later became members of the 43 Group. Geoff Beling was a close fellow artist and Lionel Wendt came very often from Colombo. He would stay for weeks at a time. Lionel was gruff and stern but his brother Harry was a sweet soul. “Oh, Lionel,” he said as I snuggled up to him on the couch, “I wish I had been born a girl! You would have found me a husband and I could have had many little children!” “Umph!” grunted Lionel.

Lionel was a world traveller who visited Brazil and Argentina. He spoke Spanish and Portuguese. Sometimes he went to Europe and after a visit to Paris brought me a white voile dress, hand-painted with tiny flowers. He brought me the latest books for children – Orlando the Marmalade Cat, The Story of Babar, and so on. Every book was inscribed “To Diana Keyt with love from LW.” The way he wrote his initials was inspired by some Arabic writing in an ancient Egyptian temple. I had my own bookshelf for my library.

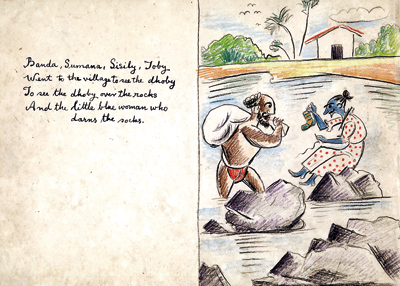

Frequent visitors were Peggy’s teacher colleagues from Hillwood. Anula Pilimatalawa, Edith Ratwatte and Sujatha Aluwihare were some of them. At teatime we would hear them chatting while walking down to our house after school. All these Aunties were almost members of the family. When Sujatha married and left Kandy, I missed her and Daddy put her into the book: “Auntie Suja comes so seldom, I almost forget her face.” Our dentist was a little man and we thought that he may have had a horse. Also in the book were Aunty, Mummy and our dog Plato. Villains of my world were snails (gombellas) who destroyed my grandmother’s flower beds. Nightmares of “Gombees” disturbed my sleep. Our parrot kept up a lively chatter and punctuated the drowsy afternoons with his shrieks.

The cook, Hinni Menika (Hinni Amma), was in charge of the animals. When Peggy was in the kitchen one evening talking over the daily meals, Hinni Amma stirred the pot of boiling rice and the aroma of hot rice got Polly animated. “Amma, bath, Amma bath!” he shouted in the voice of a small child. Bath is the Sinhala name for rice. HinniAmma became enraged at being betrayed by the parrot. “Shut your mouth,” she yelled, throwing a cloth over Polly’s cage. “Oh, so that’s why we have to keep getting so much extra rice,” laughed Peggy. Polly was imitating Hinni’s grandchildren who often dropped in for a snack or a meal. Everybody knew this, but it annoyed Hinni when the parrot tattled on her.

During my second birthday party, the grownups noticed that all the children had vanished. I and all my guests were discovered in the kitchen fascinated, examining Hinni Amma’s open mouth. She had only one tooth left and this, the most amazing object in our house, had to be shared with my little guests.

Before Plato, Jupiter was the family dog. He was an insanely active little terrier whose self-appointed task was guarding our territory. He patrolled the house verandahs and even the ‘jungly’ area behind our garden. The crows had established a colony there and Jupiter, barking hysterically, dashed at any impertinent bird who dared to approach the kitchen looking for scraps. The crows enjoyed teasing him and would walk slowly up to him and then fly away from him at the last moment making him bark and snap his teeth in frustration. One evening Jupiter did not come to Hinni for his dinner. Daddy and Mummy went to the garden at intervals all night whistling and calling, “Jupiter, Jupiter, where are you?” The next morning the servants went on a search and found him bloated with poison, stiff and cold in a patch of dry leaves. He had seen a cobra and nipping at it to drive it away had been bitten. He must have been dead all night. They gave a ‘dane’ (alms giving) for Jupiter to the crows who feasted on the food offered. To replace Jupiter, a friend gave us a long eared spaniel, Plato, who was as calm as Jupiter had been excitable.

So the days went by from the break of dawn to the fall of night when I was back in my little blue bed. At the end of his life my Daddy sent for me to say goodbye. I sat by him and reminisced about the house at 10, Upper Lake Road, and our visits to the Malwatta Vihare. I spoke of the stories and games we had shared and he exclaimed, “Why, you were not even two years old then!” But to me those events were as bright and vivid as if they had happened only yesterday. As I sat there holding his hand and gazing into his blue grey eyes his face brightened.

My son, Gawain with his wife Nelum had come for their daily visit. He had become so fond of them and had special grandfather names, Haime and Leonora, or something like that for the couple. “I still have that book you made for me so long ago,” I told him. I described the pictures and we both recited the verses to the grandchildren. He remembered the book as if he had made it that very day. I went home to New York, but when he died, Gawain was with him. It was a comfort to know that he had died with a child of his blood by his side, and not among strangers.

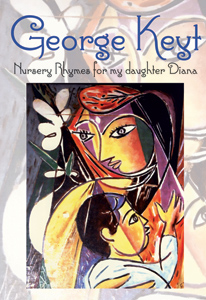

This book of verses and drawings was complete just before my third birthday and my father gave it to me then. Now decades have passed since he died and it is time to share it with other children. It is reproduced in a facsimile edition which gives an idea of what the original looks like even though the years have faded its colors. Included in the book are photographs from our family collection and on the cover is a portrait my father painted of me with my first born child.

This is the first time these very personal images will go out into the world. Even now as I turn its pages I feel I am back in that happy place. In my mind I hear the wind in the rain trees and the sound of evening music floating over the water from the temple across the lake.

(The book priced at Rs. 2490 will be available at Vijitha Yapa Bookshops from November 14)