Sunday Times 2

The Kennedy temptation

NEW YORK – Fifty years ago this month, President John F. Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas, Texas. Many Americans believe that this tragic event marked the loss of national innocence. This is nonsense, of course. The history of the United  States, like that of all countries, is soaked in blood.

States, like that of all countries, is soaked in blood.

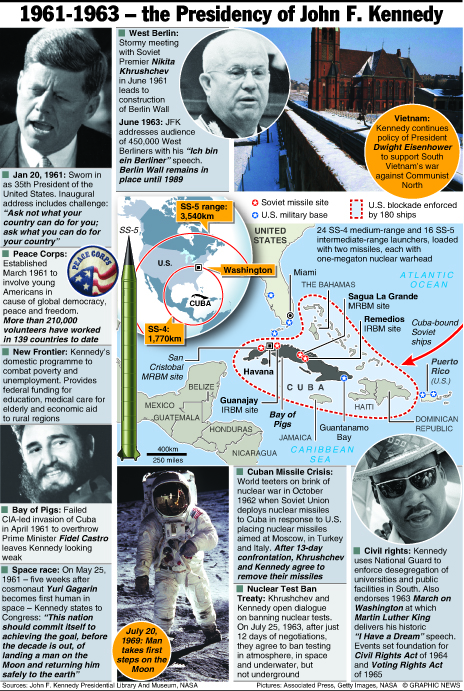

But, seen from today’s perspective, Kennedy’s presidency seems like a high point of American prestige. Less than five months before his violent death, Kennedy roused a huge gathering of Germans in the center of Berlin, the frontier of the Cold War, to almost hysterical enthusiasm with his famous words, “Ich bin ein Berliner.” (I am a Berliner.)

For many millions of people, Kennedy’s America stood for freedom and hope. Like the country he represented, Kennedy and his wife, Jacqueline, looked so young, glamorous, rich, and full of benevolent energy. The US was a place to look up to, a model, a force for good in a world full of evil.

This image would soon be battered badly by the murders of Kennedy, his brother Bobby, and Martin Luther King, Jr., and by the war in Vietnam that Kennedy had initiated. If Kennedy had completed his presidency, his legacy almost certainly would not have lived up to the expectations that he inspired.

For a brief moment, when Americans voted for their first black president, another young and hopeful figure, it looked as if the US had regained some of the prestige that it enjoyed in the early 1960s. Like Kennedy, Barack Obama delivered a speech in Berlin — to an adoring crowd of at least 200,000 people, even before he was elected.

That early promise was never fulfilled. In fact, US prestige has suffered much since 2008. America’s national politics is so poisoned by provincial partisanship — especially among Republicans, who have hated Obama from the beginning — that democracy itself looks damaged. Economic inequality is deeper than ever. And highways, bridges, hospitals, and schools are falling apart. Compared to major airports in China, those around New York City now look primitive.

In foreign policy, the US is seen as either a swaggering bully or a dithering coward. America’s closest allies, such as German Chancellor Angela Merkel, are furious about being spied upon. Others, notably in Israel and Saudi Arabia, are disgusted by what they see as American weakness. Even Russian President Vladimir Putin, the autocratic leader of a crumbling second-rate power, manages to put on a good show compared to America’s tarnished president.

It is easy to blame Obama, or the reckless Republicans, for this sorry state of affairs. But that would miss the most important point about America’s role in the world: The same idealism that made Kennedy so popular is also driving the decline in America’s international prestige.

Some of Kennedy’s most ardent admirers still like to believe that he would have prevented the escalation of the Vietnam War had he lived longer. But there is no evidence for that at all. Kennedy was a hardened Cold Warrior. And his anti-Communism was couched in terms of American idealism. As he said in his inaugural speech: “[W]e shall pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe, to assure the survival and the success of liberty.”

Enthusiasm for America’s self-proclaimed mission to fight for freedom around the world was dented, not least in the US itself, by the bloody catastrophe of Vietnam. An estimated two million Vietnamese died in a war that did not free them.

It took another, far more limited disaster to revive lofty rhetoric about the liberating effects of US military power. The reasons why President George W. Bush chose to go to war in Afghanistan and Iraq were no doubt complex. But the language used by those wars’ neo-conservative promoters came straight from the Kennedy era: the spread of democracy, the cause of liberty, and the universal authority of “American values.”

One reason why Americans elected Obama in 2008 was that the rhetoric of US idealism had once again led to the death and displacement of millions. Now when US politicians talk about “freedom,” people see bombing campaigns, torture chambers, and the constant threat of lethal drones.

The problem with Obama’s America is rooted in the contradictory nature of his leadership. Obama has distanced himself from the US mission to liberate the world by force. He has ended the war in Iraq and soon will end the war in Afghanistan. And he has resisted the temptation to wage war in Iran or Syria. To those who look to the US to fix all of the world’s ills, Obama looks weak and indecisive.

At the same time, however, he has failed to close the grotesque US prison at Guantánamo Bay. Those who leak news of domestic and foreign surveillance are arrested, and the use of lethal drones has increased. Even as open warfare is reduced, stealth warfare intensifies and spreads. And America’s image sinks further every day.

But the main problem is not Obama; it is the hubris of Americans’ belief in their “exceptional” role in the world — a belief that has been abused too many times to promote unnecessary wars. Not only has Americans’ idealism led them to expect too much of themselves, but the rest of the world has often expected too much of America. And such expectations can only end in disappointment.

Ian Buruma is Professor of Democracy, Human Rights, and Journalism at Bard College, and the author of Year Zero: A History of 1945.

Copyright: Project Syndicate, 2013. Exclusive to the Sunday Times

www.project-syndicate.org