News

Bus depots go bust with workers unpaid

Susantha Jayasiri, 37, is worried that he won’t be able to buy his children schoolbooks and shoes next term. Two grocers who gave him food on credit have stopped. He has taken loans from a number of relatives and friends who make sure they drop by his place at least once a day seeking repayment.

His daughter’s only pair of shoes, shabby and worn-out, lie drying in the front yard after a scrub. Susantha’s wife will take them to the cobbler next week to extend their life. Susantha, from Yaddigama in Maho area in the Kurunegala district, is a conductor attached to the Sri Lanka Transport Board (SLTB) Maho depot, one of about 200 workers there who held protests this week demanding that their salaries be paid.

Maho depot at a standstill since December 2. Pix by Nilan Maligaspe

The issue is clouded by claims of mismanagement by bosses and corruption by employees. “All the employees of this depot are left helpless because their salaries aren’t being paid on time,” said Jayatissa Dissanayake, 46, Chief Clerk of the Maho depot. “Their children go to school hungry and some have had to stop going to extra classes and other educational institutes because they haven’t been able to pay the fees for months.”

He said that the protest, which was launched on Monday (December 2), will be continued until all the arrears are paid. Part of the three-month wages backlog was paid when the protests started but protesters say they are still owed a month’s pay.

Half the employee’s salary – Rs. 11,600 – is paid into his bank accounts by the state Treasury. The rest comes from the revenue collected by the depot.

SLTB Vice Chairman L.A. Wimalarathne

“We are given the Rs. 11,600 on time but this is not enough to feed a family. Many of us have taken bank loans to build a house or spend on a child’s wedding, so when the money from the Treasury goes into the account it is deducted by the bank for loan repayments, leaving just a few thousand rupees for a whole month,” said H.M. Premarathne, 49, another conductor.

He said that the depot was running at a loss. “All the money we collect is spent on other expenses. Even the diesel for the buses is bought on credit, and the management owes Rs 700,000 to the gas station. How can they do all this from the income we get? Something has to be done about this.”

This is not the first time the Maho depot employees have taken to the streets. A few years ago they launched a protest in similar circumstances and returned to work after their pay arrears were settled.

This year, matters are worse. Susantha is one of those who are living in great hardship. His two eldest children have hearing defects and both their hearing aids are damaged and need immediate replacement.

“How can we find money for this if my husband is not getting paid? My children can’t hear well without the devices and at school they face many difficulties. Why don’t people in higher positions understand such things?” asked Susantha’s wife, 40-year-old Anoma Damayanthi.

Anoma said the bicycle and motobike her husband had obtained on hire purchase had been repossessed by the leasing company as the family could not make payments. “My children loved to play with their bicycle. It was heart-breaking to watch them see the bike taken away. Like any mother I want my children to have a good life. Why can’t we get the money that my husband worked hard for? Sometimes I feel like committing suicide because of these problems,” said Anoma, wiping a tear from her cheek.

The Ceylon Transport Board, North Western Province Chief Regional Manager, Rohana Tudor Chandrasiri, said the salaries could not be paid on time because the Maho depot had a low revenue stream.

“This is because there is a lot of corruption taking place there. Through inspections we found out that there is a group of employees who sell diesel and spare parts of buses illegally. Until this is stopped this depot cannot be improved,” he said.

The Manager added that discussions with the protestors had been futile.

“They should understand that they are using public money. I tried explaining to them that the fraud should be stopped. I explained that they have to work efficiently and salaries can be paid on time,” he said.

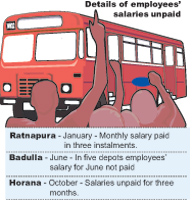

This was not the first protest this year by SLTB employees demanding their salaries. Depots in Avissawela, Horana and Badulla were among others where the workers took to the street. The Sunday Times also learns that from the 119 depots in the country only 50-60 had been able to pay salaries on time.

SLTB Vice Chairman L.A. Wimalarathne said the problems stemmed from mismanagement in certain depots. He said all depots could earn a solid income if the workers and higher authorities worked hard and competently.

“There is also an excess of buses compared with the number of commuters. This greatly affects revenue,” he said. “There are private buses running on all the profitable routes, some without permits, and this has also affected the state transport system,” he said.

Susantha Jayasiri and his family: Facing hard times

The Vice Chairman also said a number of buses were in poor condition and it was costly to maintain them.

“Sometimes it is unprofitable to put these buses on the streets because people prefer to go in buses that are in good condition,” he said.

The SLTB had been holding discussions with officials and trade unions of depots carrying salary arrears.

“Through the discussions we explain to them how important it is to work efficiently and effectively to collect good revenue. Some depots have improved through this guidance,” he said.