Sunday Times 2

China, India in race to exploit Indian Ocean seabed

China has launched a major new mission to explore the deep seas, building the only manned submersible in the world capable of navigating the ocean floor at 7,000m (23,000ft) below sea level. Pic courtesy chinesedefence.com

A serious and a cracking battle is about to begin in the deep Indian Ocean seabed as China moves to explore polymetallic sulphides in the southwest Indian Ocean ridge – an area beyond national jurisdiction of any state.

Polymetallic sulphides are sulphide deposits found at water depths of 3,700 m. in mid ocean ridges, back-arc rifts, and seamounts. They often carry high concentrations of copper (chalcopyrite), zinc (sphalerite), and lead (galena) in addition to gold and silver. Many of the metals contained in seabed deposits are considered ‘technology metals’ and are increasingly required by high technology industries including electronics and clean technologies, such as hybrid cars and wind turbines. As opposed to the generally well-studied deposits on the land, many of the resources at the bottom of the sea are yet to be discovered.

Intensity of this conundrum reached new proportions when India’s Deputy External Affairs Minister E Ahamed was questioned in Rajya Sabha on December 3 on this. He responded that the Government was aware that the International Seabed Authority (ISA) had approved the plan of work for exploration of polymetallic sulphides by China Mineral Resources Research and Development Association (COMRA),”

A Chinese submersible places the national flag on the seafloor in the South China Sea. Pic courtesy chinesedefence.com

The role of International Seabed Authority

A state party to the UN Convention on Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) should get the clearance from the International Seabed Authority (ISA) before the exploration of deep sea bed beyond the areas of national jurisdiction. Both China and India being parties to the Convention have applied for exploration clearance in the Indian Ocean Seabed.

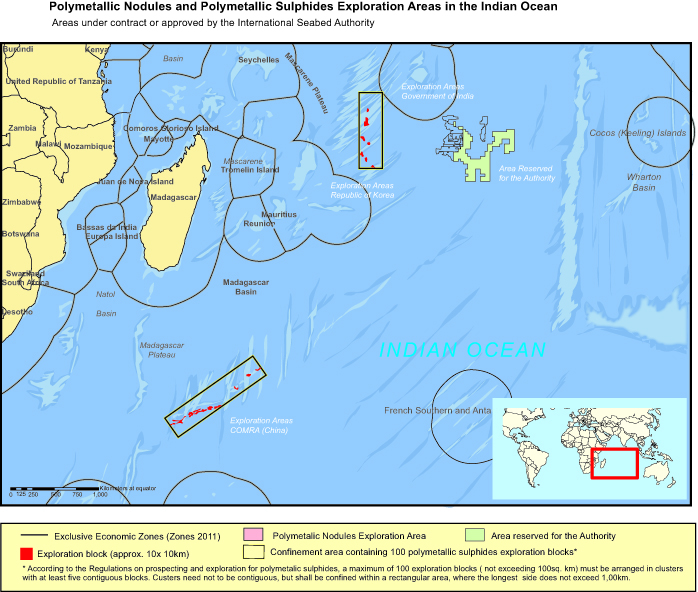

The international seabed area — the part under ISA jurisdiction — is defined as “the seabed and ocean floor and the subsoil thereof, beyond the limits of national jurisdiction. The international seabed area beyond national jurisdiction has been declared the Common Heritage of Mankind. The mineral resources of the Common Heritage are administered by the International Seabed Authority. Recognising the economic and technological imbalance between developed and developing countries, the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea and especially its part IX places emphasis on the equitable sharing of benefits derived from the minerals of the Area. The official exploration map taken from the ISA indicated the exploration areas in the Indian Ocean.

In the southwest Indian region in the map show the exploration area of China. This map also shows the areas applied by the other countries including India.

The geo-political battle for deep seabed resources

In 2011, cementing its foothold in India’s backyard, China signed a contract with the ISA to gain rights to explore polymetallic sulphide ore deposits in the Indian Ocean over the next 15 years. The contract awarded China’s Ocean Mineral Resources Research and Development Association exclusive rights to explore a 10,000-square-km of international seabed in the southwest Indian Ocean.

According to the contract, the Chinese association will have to give up 75 per cent of the ore deposit region within 10 years before enjoying pre-emptive rights of mining the remaining 2,500-square-km. The Chinese association will also have to fulfil specified duties of conducting environmental monitoring, environmental baseline research and training scientific workers for other developing countries, according to the contract.

India’s Directorate of Naval Intelligence reportedly expressed its reservations to the Indian Government about the deal which it believed could provide an excuse for China to operate its warships besides compiling data on the vast mineral resources in India’s backyard.

On March 26, 2013, the International Seabed Authority received an application for approval of a plan of work for exploration for polymetallic sulphides submitted by the Government of India. The application area is in the Central Indian Ocean and that the applicant has elected to offer an equity interest in a joint venture arrangement with the ISA-run Enterprise in lieu of a reserved area. The applicant has also elected to pay a fixed fee of US$ 500,000.

Environmental Concerns

The JOGMEG (Japan) and COMRA (China) applications for cobalt crust exploration and ESSO (India – Indian Ocean) sulphides applications are all proposed to be granted without mainstreaming environmental considerations as part of the process, without any means for consideration for marine pollution areas (MPAs). The ISA needs to develop methods of protecting ecologically and biologically MPAs on the seabed.

Also, ISA needs to find ways to establish representative networks of MPAs, including inside areas approved for exploration and, later, for exploitation. The ISA needs to find ways of preventing vulnerable marine ecosystems (VMEs), especially those protected from bottom fishing, from being damaged by exploration or exploitation, including hydrothermal vents and cold seeps; further ISA needs to implement transparency provisions, as approved in the Environmental Management Plan.

The legal and regulatory environment of the deep sea is rapidly changing, as is the technology, and as are the deep seas themselves, particularly through climate change and ocean acidification. The global community is engaged in ongoing discussions on the protection of marine biodiversity in areas beyond national jurisdiction, and considering entering into negotiations for an implementing agreement to this end. Constantly debated issues include the access to and sharing of benefits of marine genetic resources in areas beyond national jurisdiction and the conservation of marine biodiversity, and the establishment of MPAs and the conduct of environmental impact assessments. These discussions are made necessary by, and framed by, a keen awareness of the rapidly changing threats to the deep sea like climate change, ocean acidification and other anthropogenic stressors.

The ISA regime: How does it operate?

An element of the regime for the international seabed area is the so-called “parallel system”, whereby, in the case of polymetallic nodules, an application must be sufficiently large and of sufficient value to accommodate two mining operations of “equal estimated commercial value”. One part is to be allocated to the applicant and the other is to become the reserved area. The reserved areas are set aside for activities by developing States or by the ISA through its Enterprise. Once a state party makes an application, a contract is signed after assessment by the Legal and Technical Commission and approved by the Council of the ISA.

Contractors have signed exploration deals with the ISA within areas in the Clarion-Clipperton Fracture Zone, the Central and Southwest Indian Ocean, in the central part of the Atlantic Ocean and in the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. At present, there are two areas being explored – that of the Clarion-Clipperton Fracture Zone near Hawaii and in the Central Indian Basin of the Indian Ocean. For sulphides, exploration takes place in the Southwest Indian Ridge and in the Mid-Atlantic Ridge.

For the exploration of nodules, the area for exploration allocated to the contractor is each of 75,000 sq. km. For sulphides, the exploration area allocated to the contractor is 10,000 sq. km and consists of 100 blocks of 100 sq. km each.

Regulatory code

The “Mining Code” refers to the whole of the comprehensive set of rules, regulations and procedures issued by the ISA to regulate prospecting, exploration and exploitation of marine minerals in the international seabed Area. All rules, regulations and procedures are issued within a general legal framework established by the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea and its 1994 Implementing Agreement relating to deep seabed mining.

To date, the ISA has issued Regulations on Prospecting and Exploration for Polymetallic Nodules in the Area (adopted 13 July 2000) which was later updated and adopted on July 25 this year; the Regulations on Prospecting and Exploration for Polymetallic Sulphides in the Area (adopted May 7, 2010) and the Regulations on Prospecting and Exploration for Cobalt-Rich Crusts (adopted July 27, 2012).

These regulations include the forms necessary to apply for exploration rights as well as standard terms of exploration contracts. The complete set of these regulations will form part of the Mining Code together with recommendations by the Authority’s Legal and Technical Commission for the guidance of contractors on the assessment of the environmental impacts of exploration for polymetallic nodules.

Conclusion: What is Sri Lanka’s take?

It is important that Sri Lanka begins to engage in deep seabed matters through ISA in its foreign policy deliberations – for its own benefit, protection and future survival. Even in maritime workshops and conferences, deep seabed resources and its policy aspects are hardly discussed, even less on foreign policy deliberations and marine security discussions.

Cynic may claim that Lanka is too poor to engage in such issues, but it is the considered view that for its future survival, Sri Lanka should play a far more engaged role on ISA deliberations through its foreign policy and raise its concerns. But who cares? Today, hardly few knows what ISA is, leave alone to have a permanent representative to represent us, regularly. When all this was happening; when China and India made applications, where were we? Even the advisory and policy papers on maritime affairs have not touched on this aspect. It seems that Sri Lanka, when all this is brewing, has lost without a fight.

The writer is an attorney-at-law, Chartered Shipbroker (UK) and Nippon Fellow of the UN ITLOS (International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea)