Sunday Times 2

Lanka’s own crusader against apartheid

Among all the pens carried in to South Africa in the early 1980s was one that concealed a secret. Hidden in its casing was a microfilm, a mini-reproduction of an extraordinary book that would soon be printed and distributed widely through underground, anti-apartheid networks. Published originally by a Sri Lankan professor in distant Australia, it was titled, ‘Apartheid: The closing phases?’ Banned in South Africa soon after its publication, the book’s most notable feature lay in the contents of chapter 8, which asked a loaded question: ‘What can be done?’ Its author, a certain C.G. Weeramantry, had a few ideas. In fact, he had 51 of them.

C.J. Weeramantry: Recalling his days in South Africa. Pic by Indika Handuwala

Seated on a couch in his apartment, the book in his hand illuminated by a flood of natural light from a nearby window, Judge Christopher Gregory Weeramantry remembers meeting Nelson Mandela at an international conference. “Suppose there’s a room like this, filled with 50 people, when Mandela comes, there’s a kind of glow that spreads all over the room. You can see the room transform, he had that sort of personality – always with a smile; he exuded good will.” By the time the two men encountered each other in person, people had paid in blood and tears to shut an evil system down. Though these were better circumstances under which to finally meet, if he had had his way Judge Weeramantry would have met Mandela years ago. Unfortunately, in the 1970s the latter was behind bars, imprisoned on Robben Island and out of the reach of a foreign lecturer in law.

When Stellenbosch University invited Judge Weeramantry to become a Visiting Professor, they also offered him the security of being an ‘honorary white man.’ It was a confirmation, if he had needed it, that the University lay at the heart of the Afrikaner establishment. Overwhelmingly white in both its demographic and official stance, it counted among the ranks of its graduates successive Prime Ministers of South Africa. Having summarily turned down the dubious distinction of being included in the ruling class, Judge Weeramantry made his own terms clear: he would speak as he wished in the lecture room, he would meet whomsoever he wished to meet and he would go wherever he wished to go.

The University, keen to have an acknowledged expert on the Roman Dutch law of contracts, share his knowledge, accepted his terms, and to their credit they upheld them – even when they discovered there was a dissident in their midst. For his part, Judge Weeramantry knew he was placing himself in a dangerous situation – he was stepping into a society divided and he was disinclined to self-censor. Still, this was an opportunity not to be missed, for someone so interested in human rights must necessarily be interested in examining their “total violation” as manifest in apartheid in South Africa. Extending their support to him, the University of Monash, then his employers, allowed him a leave of absence and Judge Weeramantry got on a plane.

Nelson Mandela: Pic courtesy AFP

Writing about his arrival in South Africa, he would later note: ‘the visitor’s first impact with apartheid is an unforgettable experience.’ From this point on, everything he would see would be divided: from signs on public toilets to entire neighbourhoods, the distinction between ‘coloureds’ and ‘whites’ was absolute. In the days that followed, he would come to know the country well – and he was unequivocal in his verdict. “Apartheid was totally opposed to every principle of human rights and equality. Remember, I had the freedom to go where I wanted and meet whoever I wanted. I went down into the mines and met the people there, I went into the black dormitories and saw how they lived. I went to the heights of power where even the Supreme Court judges would entertain me. So I saw it from top to bottom, as few other people had seen it.”

Escaping the confines of Stellenbosch University’s grounds, Judge Weeramantry would head out, escorted by an ever rotating cast of people who were sympathetic to the anti-apartheid movement (that there were a number of extremely committed white activists is something he takes care to highlight). He visited the black homelands and centres of influence, met leaders of the community and witnessed the appalling conditions in the shanty towns first hand. He even met with members of the Indian community. What he saw made a deep impression on him: it was a system rife with brutality, corruption and exploitation, built on the humiliation and utter degradation of an entire people. It was a system that could not be allowed to continue.

Already, heroes of the resistance had been identified. “When I was there, Mandela’s name was on everyone’s lips, he was already

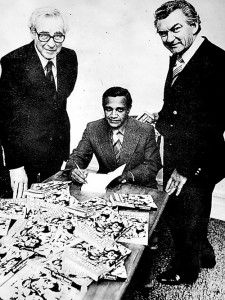

At the launch of 'Apartheid: The closing phases?' in Australia: Former Australian Prime Minister Bob Hawke (right) C.G. Weeramantry (centre) and Sir Richard Eggleston, Chancellor of Monash University

outstanding,” says Judge Weeramantry. Though he tried to see him, he discovered that Robben Island was impenetrable. Prisoners were beyond the reach of even their families. However, even with the likes of Mandela behind bars, change was in the wind. Writing in his memoirs, Judge Weeramantry noted ‘whereas on the surface it seemed that apartheid was solidly established and apparently set to last indefinitely, the observations I was able to make on the ground enabled me to see that things were moving and that there was not merely an element of hope but a certainty of change.’

Returning to Australia, Judge Weeramantry began writing the volume that he eventually titled ‘Apartheid: The closing phases?’ It began with vignettes, potent literary snapshots of what it was like being in South Africa under apartheid. What followed was a comprehensive assessment of the situation. Beginning with the puncturing of the various rationales supporting apartheid, the author went on to examine its cost, assess obstacles to black equality and analyse the political scenario. He presented ‘White South Africa’ and ‘Black South Africa’ side by side, thereby providing a shocking contrast. He exposed the hypocrisy of its ruling class and then, step by step, outlined what could be done to demolish the entire vile institution.

His aim throughout was a peaceful transformation of the country and in that he had the most amazing allies: people like Nelson Mandela and Desmond Tutu; leaders of transcending grace and wisdom without whom such a thing could not have even been imagined. While some of his suggestions had been made before, this was perhaps the first time they had been compiled into so thorough a list.

Reading from them now, you can see that no stone was to be left unturned – trade unions all over the world should mobilise; South Africa should be made to feel the brunt of disinvestment, declined bank loans and patent applications; the Church should cast the full weight of divine disapproval on apartheid, while individuals should write letters, stage boycotts and pursue fact-finding missions to see for themselves what the system entailed. Foreign policy must be shaped to condemn apartheid across all the nations of the world, while legal systems should be tapped to challenge apartheid in the courts. Last but not least, all that could be done to awaken the Afrikaner conscience should be done.

It was his intention, says Judge Weeramantry, to demonstrate how a powerful and concerted protest could overturn even the most entrenched of systems and in that he succeeded. Though itwas long since he left, his friends in the country would write to tell him of the impact his book had had. It had been secretly reprinted twice and when he returned to South Africa after the end of apartheid, it was to discover it had been unbanned. The sea-change the country had undergone was captured in a single picture. Judge Weeramantry remembers the moment well: standing alongside lecturers from Stellenbosch University, smiling and proud, they openly held copies of ‘Apartheid: The closing phases’ up for the inspection of the camera.