Sunday Times 2

Life under apartheid

View(s):I live in Atteridgeville, a township outside Pretoria. Like many townships in South Africa, this is where black people were moved to; we had to live far from white people.

The enemy was clear to all of us in the township – it was the white man.

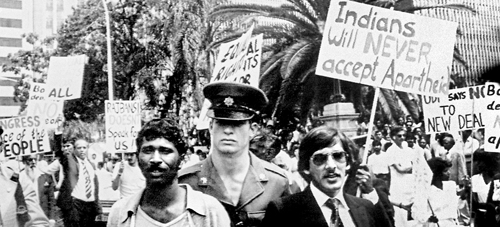

Resistance to Apartheid is largely based in the nonviolent teachings of Mahatma Gandhi. A policeman arrests two Indian men of South Africa, on November 14, 1983 during a demonstration against Apartheid outside Durban city Hall (AFP)

We knew that we had to destroy the apartheid government at all costs.

It was a difficult time for us as black people.

You always lived in fear, worried that you might get arrested for being in the wrong place or simply because a policeman looked at you and decided they didn’t like you.

I knew it wasn’t fair for me to get treated like an animal simply because I was black – but they didn’t care about what was fair.

Everything about the apartheid system was designed to make us feel inferior and it worked, I felt less important than “baas” (Afrikaans for boss).

I don’t know why they hated us – I just know that they did and very much.

Many of us were not formally trained like the men who were part of Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK), the armed wing of the African National Congress (ANC) but we were involved in the struggle in our own way, we called ourselves “street soldiers”.

If there were police coming into the township to raid homes and arrest people who were believed to be “terrorists” by the security forces, we did all we could to protect them. We hid them in our homes and kept the police away by blockading the streets with burning tyres or large rocks.

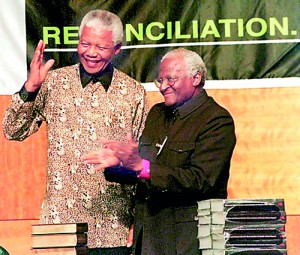

In 1995, Desmond Tutu leads the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) in gathering information and data on the human rights violations of the Apartheid era. In 1998, the TRC brands Apartheid as a crime against humanity South African President Nelson Mandela (L) with Archbishop Desmond Tutu, acknowledges applause after he received a five volumes of Truth and Reconciliation Commission final report from Archbishop Tutu, in Pretoria 29 October (AFP)

Travel restrictions

The motto at the time was “liberation first, education later” – as a result many of us did not go to school.

We couldn’t go to school while our people were being oppressed, we didn’t care about anything but fighting.

There were various laws which reminded you on a daily basis that you were black.

The pass law meant you had to carry a “dompas” (Afrikaans for stupid pass, as it was called by black people) if you were going to move outside designated areas such as the “homelands” and townships, into “white South Africa”.

But you would also get stopped in those areas and you had to produce your “dompas”.

It showed if you had permission to be in that area and for how long.

Urban areas were strictly for whites; if the police stopped you there you had to have a special permit to be there and if you didn’t, the police would throw you in the back of a van and arrest you.

Life was worse for those of us who were seen to be activists; the police would come to your home in the dead of night, kick down your door and drag you away kicking and screaming.

Many people disappeared without a trace during those home raids.

If you were lucky you would only get tortured and dumped somewhere; if you were lucky they would let you live.

I can’t even talk about that time without still feeling angry, without feeling pain.

As we approached South Africa’s liberation in the early 1990s things began to change, certain laws became more relaxed, you could see that there was a big change coming. I was filled with joy and excitement at the news of the release of the “magnificent seven”, in 1989 – the likes of Walter Sisulu and later Nelson Mandela.

The impossible had become possible at last.

Sunset clause

I thought I’d finally be able to afford that kind of life whites enjoyed, that we would live side by side as brother and sister but for many of us that hasn’t happened.

The same people that told us to give up school and take to the streets for their release from prison and our liberation as black people came into power and then forgot about us, they called us the lost generation.

They had nothing for us. I felt used, I still feel used.

There can be no doubt about the fact that not only has the Mandela settlement with the [FW] de Klerk regime compromised the poor black people it has also impoverished them even more.

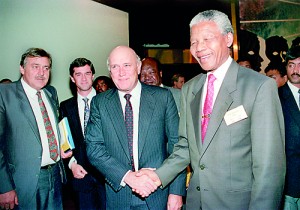

African National Congress President Nelson Mandela (R) shakes hands with South Africa's President Frederik W. de Klerk (C) as South African Foreign Minister Pik Botha (L) looks on, 15 May 1992 in Johannesburg, after the first day of the Convention for a Democratic South Africa (CODESA)(AFP)

Nice-sounding phrases such as “the sunset clause” which guaranteed the ill-gotten wealth of whites and the protection of the public service jobs held by whites were the cherry on top for whites.

The only thing blacks got was the vote after every four years and the spattering of a few black elite [politicians] whose aspiration is to be next to Mandela and those of his ilk. Today I work as a mechanic, I have no formal qualification; everything I know about fixing taxis I taught myself – this government of black people does not care about me, it has no time for me.

Yes we are free to go where we want to without fear but we are still not free, not in economic terms. What you have in South Africa now is a handful of black people looting the scraps off the table left by those who control the economy; our leaders are enriching themselves now while the majority still have nothing – that is what has become the legacy of our freedom.

Those who died for this freedom sadly died for nothing in my view.

(Courtesy BBC)

| Main Apartheid Laws

Group Areas Act, 1950: Forced physical separation between races by creating different residential areas for different races. |