Sunday Times 2

On the cutting edge

The biomedical in biomedical engineering ensures that Angelo Karunaratne’s raw materials are quite distinct from his counterparts who specialise in say, aeronautics. His playing field is the bridge that links medicine and engineering and he works not just with plastic and metal but with living tissue. With the completion of his PhD, the young Sri Lankan researcher has won acclaim, first walking away with the Best Doctoral Thesis in Biomechanics as adjudged by the European Society of Biomechanics Council and more recently a 2013 Young Investigator Award (merit) at the International conference of Biomedical Engineering in Singapore earlier this month.

While Angelo can now lay claim to the title of ‘Dr.’ it wasn’t exactly what his parents had in mind for their son. Nimal and Renuka Karunaratne dreamed of him becoming a doctor, their hope fuelled by how he excelled as a student at St. Peter’s College where he also captained the athletics team. He got eight As in his O/Ls and chose bioscience with a career in medicine in mind. However, when he failed to gain admission to local universities, tough decisions were called for. There was no question of studying medicine abroad, he knew they couldn’t afford it, but Angelo convinced his parents that if they could put up the money he needed for his first year and a half at Queen Mary University, London (QMUL), he would do the rest. The fact that his aunt lived in the UK helped them decide in favour of his plan.

That first year was a taxing one, says Angelo, who got a job at a supermarket chain to help pay the bills. Still, knowing what his family had given up to allow him this opportunity meant the young student didn’t squander his time at university. Instead, he worked hard, both inside and outside the classroom, coming in second overall when he graduated and accepting a promotion to supervisor at his

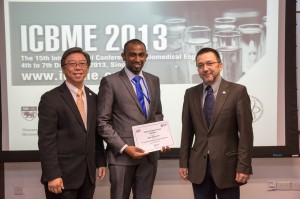

Angelo Karunaratne (centre) wins the Young Investigator Award at the International conference of Biomedical Engineering

“In medical engineering you take a medical problem and try to find an engineering solution,” says Angelo. Biomedical engineers like him have a vast and incredibly exciting field to play in: you see their work in the simplest of electron microscopes, the MRI, ultrasound and CT Scan machines but also in the likes of cutting edge robotic surgeons and computer assisted surgery, the development of ever more effective joint replacements and artificial organs as well as the use of nanotechnology in diagnosis and treatment.

At QMUL, Angelo would take on studies of the best tendon suturing methods (a visiting surgeon showed him how to tie five kinds of knots with bovine tendons that Angelo then subjected to stress tests to determine which was the most effective) and as part of a team, he later tackled artificial ligaments. Having graduated in 2009 with First Class Honours, the 24-year old Angelo set out to find a job, landing one at Depuy Orthopeadics International where he worked as a research assistant performing lab based experiments in product and mechanical testing for material used in implant manufacturing. However, three months in to his new job, Angelo received a call from his lecturer at QMUL that would plunge him back into academia. Prof. Himadri Gupta wanted to offer him a scholarship to complete his PhD.

That it was funded in part by QMUL and in part by Diamond Light Source (DLS) at Harwell, UK, meant exciting things for Angelo: for starters, his research would have immediate practical application. DLS itself was half the attraction. The UK’s national synchrotron science facility is the size of two football fields. The intense beams of light or synchrotron radiation it produces are channelled through to around 48 stations, each of which is allotted to specific researchers. For the next three years, Angelo could use one of those stations.

For his PhD, Angelo would focus on using X-ray imaging techniques to understand the nano-scale origins of structure-function relations in metabolic bone diseases. More simply, he would build a machine that would allow him to study how disease affected bone structure and mechanics at the nano-scale. Choosing to focus on rickets (because it was common and well understood, thereby making it a good way to verify his research), on osteoporosis (because of the sheer number of people affected by what Angelo dubs the ‘king of bone problems’) and finally on aging (because of the implications of a rapidly aging global population) he set about his work. His nano-mechanical imaging technique would achieve something that hadn’t been attempted before: “I would say there was no technique to look at the structure and mechanics of the sample at the same time. You can take nano-structural images with high resolution imaging techniques but to take the images when it’s in motion is quite difficult.”

The need to combine motion with nano-scale imagery lay in recreating what the stresses on the sample would be like if the person was actually in motion – say running or walking. Looking at it on a nano-scale meant that the minutest changes could be noted early on. Diseases could be caught and treated before they had become irreversible, medications could become more effective. In cases of osteoporosis for instance, patients must typically wait three months to see if new drugs are taking effect, Angelo’s machine can tell if anything has changed in three weeks. His particular focus was on quality over quantity: while conventional treatments for osteoporosis, for instance, would plug the holes in the bone left by the disease, they did not necessarily improve its quality or prevent it from fracturing or breaking.

There’s a long way to go before his machine becomes a part of standard clinical diagnosis – if it ever does. Angelo, who never worked with human samples, says they relied on genetically manipulated mice to provide what they needed for the study. In humans it would require a bone biopsy, which is a painful process, all for the required sample the size of fingernail tip. However, while it might be a decade or more before you find his technology in hospitals, drug companies will likely come knocking earlier, drawn in by the potential for early, prompt diagnosis and a chance to tweak their medications.

At present Angelo is working as a research associate at the Centre for Blast Injury studies, Imperial College London. In Sri Lanka for a short visit, Angelo is glad to be reunited with friends and family. He’s also using the opportunity to talk to the likes of the National Science Foundation about his work and hopes to teach as well.The father of a little girl and a five- month-old boy, he says he and his beloved wife Romanie want their kids to enjoy the education that he did -he knows the competitiveness of local exams gave him an edge when he studied abroad. He’s only sad that local universities don’t have room for all the promising students that come knocking at their doors. “If I hadn’t gone abroad then I wouldn’t have been able to reach this stage,” he says. Certainly, he has not shortage of fans there. Speaking at the award ceremony where Angelo was honoured for his thesis, Prof. Nick Terrill, his supervisor at DLS said simply: “We wish we could have cloned another one or two of Angelo.”