Sunday Times 2

Putin’s law: Saying no to international commitments

FLORENCE – Russian President Vladimir Putin is showing increasing disdain for international law – a stance that is perhaps nowhere clearer than in his government’s continuing military support for Bashar al-Assad’s regime in Syria. But, in view of Putin’s authoritarian rule at home, his perception of international law as little more than an instrument of foreign policy should come as no surprise.

When Putin’s regime wants to stamp out opposition, it typically deploys exotic and improbable provisions of Russia’s criminal code.For example, the young female performers in the punk band Pussy Riot, who dared to sing derogatory songs about Putin in an Orthodox church, were charged with “hooliganism motivated by religious hatred” and received two years in prison.

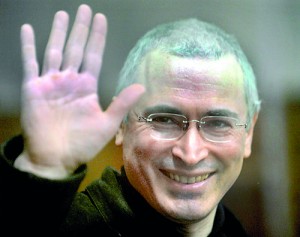

former tycoon and bitter Kremlin critic Mikhail Khodorkovsky. AFP file photo

Similarly, opposition politician and lawyer Alexei Navalny was convicted for having given poor legal advice to a provincial timber company that caused the company to lose money – a “crime” that carried a five-year prison sentence. Fortunately, the authorities suspended the sentence following mass protests in Moscow by Navalny’s supporters; but the conviction remains on the books – and has hampered further political activism.

Politically motivated trials started to increase ten years ago with the imprisonment of Mikhail Khodorkovsky, who was head of Yukos, Russia’s largest privately owned oil company, after he ignored warnings not to support Putin’s opponents. Since then, there have been hundreds of politically motivated arrests and excessive sentences. Most recently, the authorities declared a peaceful anti-government protest by a score of young Muscovites a riot, despite a live Internet broadcast showing no unrest, and no reports by witnesses of any disorder. But several protesters are now in prison or in psychiatric hospitals.

Putin’s intolerance of dissent is becoming ever more sinister. He was deeply offended by the negative reaction on the streets and in the press following his controversial election in 2012 to a third presidential term, accusing the opposition and the West of trying to undermine him. Whether this response reflects personal pettiness or the uncompromising outlook of a former KGB officer, his hostility toward the West, especially the United States, is disturbing.

At the beginning of this year, Putin demonstrated the depths to which he will sink to punish perceived opponents. After the US adopted a law aimed at sanctioning Russian officials responsible for alleged human-rights violations, Putin’s government banned American families from adopting Russian orphans, thousands of whom find happy homes in the US every year. Hundreds of children, many disabled, had already met their prospective parents and were preparing for a new life when the ban was imposed; they were told that their would-be parents had changed their minds. Families from other countries whose governments hold unfavorable views of Russian policies have also been banned. Meanwhile, 75,000 Russian children fester in squalid children’s homes.

Every year, the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) receives 10,000-14,000 complaints from Russia, the highest number in Europe. Some result in annulment of unfair sentences and compensation for victims (though Russia seldom compensates Chechens who have suffered at the hands of the Russian military).

Until now, Moscow has generally respected ECHR rulings. But, on October 23, the Russian Supreme Court for the first time officially rejected an ECHR decision, in a case concerning Alexei Pichugin, a former deputy to Khodorkovsky and head of Yukos’s security service, who had been sentenced to life imprisonment for fraud. The ECHR called for Pichugin’s sentence to be reduced and for Russia’s government to compensate him for “moral damage.”

But this was not the only case of Russia turning its back on its international commitments. The foreign ministry has announced that Russia will not comply with the decision of the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea in a lawsuit brought by the owners of a ship used by the environmental group Greenpeace.

The lawsuit stemmed from an incident in September, when Greenpeace activists, as part of the group’s global “Save the Arctic” campaign, tried to place a protest poster on Russia’s Prirazlomnaya oil platform. They were arrested by Russian border guards and imprisoned in Murmansk, and their ship, the Dutch-owned Arctic Sunrise, was also seized. Its American captain, Peter Willcox, and his international crew were searched and charged with piracy — a crime that carries a sentence of up to 15 years imprisonment and confiscation of property.

The Russian foreign ministry’s explanation for ignoring the tribunal’s ruling was as ominous as it was perplexing: Russia, the ministry declared, does not recognize the tribunal. But the tribunal was established under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, to which 166 countries, including Russia, are party. Indeed, Russia has appealed to the tribunal, and won cases, in disputes involving its own ships.

It would appear that it is Russia that is at sea. The Putin government’s increasing tendency to exempt itself from the international rule of law is dangerous for the world, but it is likely to prove more dangerous for Russia.

Andrei Malgin is the author of An Adviser to the President and writes the blog Notes of a Misanthrope.

Copyright: Project Syndicate, 2013.

www.project-syndicate.org

| Khodorkovsky flies to Germany after release

MOSCOW, Dec 21 (AFP) – Russia’s most famous prisoner and Kremlin critic Mikhail Khodorkovsky on Friday walked out of jail after more than 10 years behind bars, immediately flying to Germany following his surprise pardon by President Vladimir Putin. The former oil tycoon was quitely escorted out of his prison in northwestern Russia in a low-key operation, depriving journalists of any image of the former convict leaving his remote penal colony. In a dizzying succession of events, several hours later Khodorkovsky flew to Germany, the prison service said, with the RAPSI legal news agency saying he was on his way to Berlin. Khodorkovsky’s ailing mother Marina, 79, has been undergoing treatment in Germany, but her current whereabouts are unclear. A source told AFP his wife Inna is currently in Switzerland. Putin pardoned Khodorkovsky, once Russia’s richest man, a day after stunning the country on Thursday by saying he asked for clemency on humanitarian grounds as his mother was ill. “Guided by humanitarian principles, I decree that Mikhail Borisovich Khodorkovsky… should be pardoned and freed from any further punishment in the form of imprisonment,” said the decree signed by Putin on Friday. Less than three hours after the publication of the decree, his lawyers confirmed that Khodorkovsky, 50, had left his prison colony in the town of Segezha in the Karelia region. ‘Unprecedented in Russian history’ The release drew the curtain on the highest profile criminal case in post-Soviet Russia which has harmed the country’s investment climate and become a symbol for the selective persecution of Kremlin foes under Putin. Thirty foreign and Russian Greenpeace activists, arrested on hooliganism charges after their protest against Arctic oil drilling are also expected to escape prosecution. “It’s an unprecedented case in the history of modern Russia,” said political analyst Valeria Kasamara. “It was not worked out what to say and how — that is why they are hiding him.” “It has not sunk in yet,” Marina Khodorkovskaya, the former tycoon’s mother, told Russian state television. Speaking in a shaky voice, she said she was taking sedatives to calm her nerves. “God, he had mercy,” exclaimed mass-circulation newspaper Moskovsky Komsomolets in a banner headline. |