News

Fleeing persecution, Pakistan’s Christians find a manger in Lanka

Tears welled up in Irfan Barkat’s eyes as he accepted a Christmas hamper from a well-meaning Catholic nun. Back home, in Pakistan, the prominent human rights activist had been the one handing out baskets to the poor. Irfan is a 47-year-old Pakistani Christian who fled his country in September.

Christmas away from home: Kashmala and Rashami decorate a small tree. Pix by M.A. Pushpa Kumara

He and his family live in a single room in Mattakuliya, offered to him by the Catholic clergy. The Church supports hundreds of Pakistani Christians residing temporarily in Sri Lanka while the UN refugee agency processes their asylum applications. Prising open a tin of biscuits from the hamper, 37-year-old Yasmeen sets it down on a low stool. She brings us tea and stares with stricken eyes as Irfan relates their tale. Every time he speaks of the sacrifices their daughters—Rashami, 11, and Kashmala, 9 — have had to make, he cries.

For most of his adult life, Irfan had fought for the rights of Pakistan’s Christian minority. He was first employed at the National Commission for Justice and Peace established by the Catholic Bishops’ Conference. Among other things, he coordinated legal aid for persons accused of violating the blasphemy provisions of the Pakistan Penal Code.

In April 2010, Irfan moved to Archbishop Sebastian Francis Shaw’s Lahore office where he handled housing and land cases. One of his duties was to protect church land and the property of Christians from encroachment and grabbing.

As a spokesman for the diocese, Irfan routinely courted controversy. On March 9, 2013, mobs torched dozens of Christian houses in Lahore after a non-Muslim man was accused of insulting the Prophet Mohammed. Irfan gave multiple press statements. He criticised the government and militants. He accused the police of inaction. And he gave protection to the wife and children of the alleged ‘blasphemer’.

“Within a few days, I was the one looking for protection,” Irfan said, sadly. While he was no stranger to threatening phone calls, they now became more intense. The police took weeks to act on his complaints. When his wife and children became targets, his resolve crumbled.

Yasmeen was a teacher at the school her daughters attended. She started getting calls to her mobile phone from men who knew the colour of their clothes, their daily routine and the path they took to school. The numbers were untraceable.

One day, however, Irfan received a menacing call from an identifiable Afghan number. He pulled his children out of school and moved into a Catholic convent for safety. He started varying his schedule so that he went to or left work at irregular hours.“I survived many months with these dirty calls,” he said. “They abused me, they threatened to kidnap my daughters, to kill my wife and criticised me for standing with the Christian community.”

Temporary haven across the seas: Irfan and family in their room in Sri Lanka

The turning point came in September. An anonymous caller told Irfan he knew where he and the family had been the previous night. He also knew the time they had come and left, their vehicle number, the make and colour of their car and what clothes each of them had worn.

Irfan knew it was a matter of time before someone struck. With the Church’s assistance, he secured visas and airline tickets and they fled. In the first telephone call he made to relatives on arrival in Sri Lanka, he was told that his 79-year-old father had died overnight of a heart attack.

“It was very sad for me,” Irfan said. “We left with only our clothes and Rashami’s electric organ. Everything else that we have here, including our kitchen utensils, is borrowed. We lived comfortably in Pakistan. Here, we don’t even have a television or a fridge.”

As with other Pakistani asylum seekers in Sri Lanka, money is a problem. The children were offered a scholarship and Kashmala goes to school. But they can’t afford books, uniforms, shoes or transport for Rashami. Sri Lanka does not allow asylum seekers to work. Neither does it receive refugees. The family is transiting here for the UNHCR to relocate them to another country. It could take many months.

More than 500 Pakistani Christians have sought refuge in Sri Lanka and the Church has asked for government support, a spokesman for the Archbishop’s House in Colombo recently told the Sunday Times. Many families stay in Catholic-dominant areas such as Negombo, Maggona, Mount Lavinia and Moratuwa.

When Irfan visited the UNHCR last week to renew their asylum seekers’ certificate, he met another Pakistani Christian from Lahore. He said he lived in Negombo. “He said it was an area where so many Christian and Ahmaddiya Muslim families were living,” Irfan recounted.

The UNHCR website states that there are currently 1,030 asylum seekers resident in Sri Lanka. It does not provide a breakdown by country of origin. Pakistanis make up a majority.

Yasmeen is now worried that they cannot meet the high cost of living in Sri Lanka with the little resources they have. The Archbishop of Lahore had given them some money which will soon run out. Food and drink is more than 100 percent more expensive here than in Pakistan, she says. Even with the generosity of the Catholic clergy, it is difficult to survive.

Every evening, Irfan takes down the rosaries hanging from a nail on the wall. The family sits on a borrowed mat and prays. “We just ask God to save us, to help us,” he says. “We don’t have so many desires, just our daily needs.”

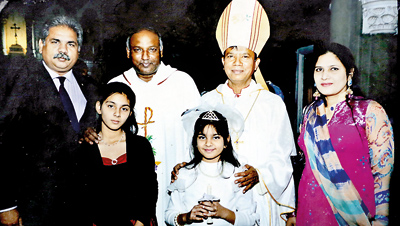

Back home: Irfan and family with Lahore’s Archbishop and Vicar General

Safety is their main priority. They will never go back to Pakistan, Irfan asserts. Two of his colleagues have also fled the country. “UNHCR can send us anywhere in the world where my wife, daughters and I can live in liberty and as human beings,” he says. “I hope they will send us to a place where food and living standards are affordable. It is very difficult for people to survive here.”

Despite everything that has happened, Irfan has no regrets. He had decided to fight the good fight because he has witnessed discrimination from childhood. There was no going back on that, he insists. What cuts him up is that religious fanatics, who make up a fraction of the Pakistani population, are holding the entire country to ransom.

In the background, his daughters are hanging decorations on a small tree. They had found tinsel and baubles in an old cupboard. Streamers hang from the windows and a frilled banner on the walls reads, ‘Merry Christmas’. It is very different to what they are used to but, like many other asylum seekers, they will just have to make do.