Sir Wilfred Thesiger and the snows of Kilimanjaro

A little while ago I was looking through my diary of an entry a little over a decade ago.

August 24, 2003:

Sir Wilfred Thesiger died today. He was the last of the great adventurers who perhaps became most famous between 1945 and 1949 when he explored the southern regions of the Arabian Peninsula, and twice crossed the Empty Quarter. I met him several times at The Royal Geographical Society, at his last “retreat” in Surrey, and then finally at a memorable lunch celebrating his 91st birthday on June 7, 2001 at The Travellers Club in London hosted by Tom Sutherland just two years before he died.

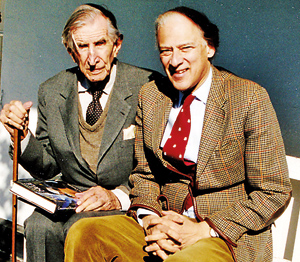

Sir Wilfred Thesiger and Christopher Ondaatje

Thesiger was an eccentric traveller and wrote two marvellous books: Arabian Sands, and The Marsh Arabs. He was born in 1910 in one of the mud buildings housing the Legation at Addis Ababa in Ethiopia where his father was British Minister. He had a wild carefree childhood in the mountains and savage panoply of the Abyssinian Empire.

Then Eton and Oxford where he won a Blue for boxing and developed a passion for remote travel. After Oxford he joined the Sudan Political Service in 1935 – visiting unknown corners of the Sudan and Chad. He won the DSO in the war serving the liberating forces in Abyssinia. After the war Thesiger devoted his life to travelling, invariably on foot, or with animal transport.

He had a fierce pride in testing his physical endurance – danger, thirst and loneliness. He was a superb writer and sensitive photographer. Later he lived among the pastoral Samburu tribe in Northern Kenya.

His final years were spent in England disillusioned with the disappearing world he had left behind. I gave him my book Journey to the Source of the Nile when I last met him in Sussex. Alexander Maitland, his biographer, said it was one of his favourites. My photograph of the two of us is one of my photographic treasures.

There were eighteen of us at the lunch held for Sir Wilfred. Among the guests were George Webb (his travelling companion), John Hemming (the Director of The Royal Geographical Society), Nigel Winser, Robin Hanbury-Tenison, Sir Mark Allen, St.John Armitage, Andrew della Casa, Michael Shaw, Andrew and Robin Sheepshank, John Shipman, Julian Lush, Sam Allan, Mike Nicholson, Hugh Leach, Christopher Foyle, Tom Sutherland and myself. There is an historic photograph of us standing around Sir Wilfred before lunch.

Kilimanjaro is a snow-covered mountain 19,710 feet high, and is said to be the highest mountain in Africa. Its western summit is called the Masai ‘Ngaje Ngai’, the House of God. Close to the western summit there is the dried and frozen carcase of a leopard. No one has explained what the leopard was seeking at that altitude.

Ernest Hemingway

The Snows of Kilimanjro

This is an extract from Thesiger’s own My Kenya Days:

I returned to Kenya in February 1962. George Webb and I had already planned to climb Kilimanjaro and we set off two days after we arrived. . . . Kilimanjaro, a huge crater, a great dome of ice and snow 19,340 foot high; and Mawenzi, a deeply eroded, steep, jagged mountain 16,900 foot high. At 15,000 feet, they are separated by a bare stony plain, the saddle of Kilimanjaro. Here, we spent the last night in the hut at the foot of Kibo. It was bitterly cold, with snow lying about in patches on the mountainside. The hut was cold and draughty. We spent a wretched night there and neither of us slept a wink owing to the altitude.

The guide called us at 1 a.m. We had some tea and biscuits and then started off up the mountain in the dark, following his hurricane lamp. There was mostly scree at first, and then, after about 3,000 feet, the slope became very steep and covered with frozen snow in which we kicked steps … We toiled up this for four hours but it was too cold to stop long. We reached the crater rim at Gilman’s Point, 19,000 foot high, just as the sun rose, an orange ball seen through the blanket of cloud on the horizon, above which towered the black, jagged outline of Mawenzi … Round the rim of the crater, the summit looked only twenty minutes away. In fact it took us two very hard hours to get there through soft snow. The last 500 feet were a desperate effort. We would go a few yards and sink down again to rest. Here we saw five wild dogs. They followed us about a hundred yards away, keeping parallel with us along the glacier on our left. It was an amazing thing to have found wild dogs at 19,000 feet, about 10,000 feet higher than they normally ever go. They looked like wolves in the snow as they followed us, or sat and watched us. I have often wondered if there is any record of mammals having been found at a higher altitude.

Dinner at the Travellers’ Club

In 2001 Sir Wilfred Thesiger was 91 years old and he had been a member of The Travellers Club for 71 of those years. He was one of the oldest and most revered members and his bust is still proudly displayed at the top of the main staircase leading to the famous Club Library with its literary treasures. The Travellers Club was formed in 1819 and the formation of the now famous Library was on the agenda of the very first Committee meeting, when it was agreed that “each member be invited to contribute a book either in whole of half binding”. The first book to enter the Library was given by Viscount Valentia who presented his account of the first British mission to Abyssinia 1802 – 1806, on which he was accompanied by Henry Salt. Both men were founders of the Club.

Today the Library remains the room in the Club most closely associated with travel. Before we sat around the oval table stretching across the centre of the Library a historic photograph of was taken. Then Sir Wilfred waited quietly at the head with his stern hawk face wondering what else we had in store for him. He had been assured that he would not be asked to speak. I remember the menu: Crab Salad with Creme Fraiche, Red Pepper Coulis, Breast of Guinea Fowl with Creamed Celeriac, Ribbon Vegetables and Parisienne Potatoes, Birthday Cake, and then Coffee and Medjool Dates. This veritable feast was served with the finest of Club Champagne, Club Red Burgundy, and Pink Champagne. The birthday cake itself was a work of art appropriately shaped with sand dunes, coated with an icing resembling sand, on which a marzipan palm tree, camel and Arab in a red turban were placed next to a deep blue pool of water. The table was decorated with palm fronds, polished black pebbles and white orchid blossoms.

After lunch, while a fine Club Tawny Port was served with coffee, Tom Sutherland, our host, welcomed us and said a few words about Sir Wilfred’s illustrious career. He then asked us to say something about our guest of honour. There were many fine short speeches and I luckily kept my notes on what I said that night. I was terribly nervous because of what I was going to say. Criticism, however well-intended, does not always go down well in intimate gatherings, especially when directed at such a well-known controversial celebrity. But I was determined to tell my story.

Gentlemen:

It was almost three years ago that I had lunch with Sir Wilfred in Sussex. I admit I was very full of myself because my book Journey to the Source of the Nile had just been published. He was very kind and full of praise. But when I talked about his Kilimanjaro exploit in 1962 and the dangerous experience of seeing the pack of wild dogs at the summit he brushed my comments aside, saying that there was no real danger and that wild dogs had never been known to attack human beings. I was shocked at his statement. But since then I have done some research, and although carnivores seldom attack and eat carnivores, there are several reported cases of wild dogs attacking humans. Bartle Bull, the author of Safari, has recounted three cases in Kenya. Wild dogs in Northern India, called dholes, are known to have attacked and stolen children from villages; and wild dog cousins in Australia – the dingoes – have sometimes fed on unwary humans camping in the bush.

Excuse my boldness in giving you honoured guests these facts. But in my opinion that Sir Wilfred and George Webb were unbelievably lucky. There is obviously a certain wariness for dogs to attack humans. But when food is short – particularly during bad weather on the cold heights of a mountain like Kilimanjaro – predators climb to unusual heights to get food. Any food. And the five wild dogs that Sir Wilfred saw must have considered the possibilities of a successful attack on the unarmed mountaineers. Curiously, the answer to Hemingway’s riddle at the beginning of his legendary masterpiece The Snows of Kilimanjaro is also not quite so enigmatic. Had the leopard lost its way? Or had it gone there to die? There is another more likely solution. Hungry and cold the leopard, close to the Western Summit, climbed to these heights looking for the easiest prey known to a well-trained predator – man.

And I left my brief speech at that. I thanked Sir Wilfred for his wonderful life which had filled us with jealousy and ambition. He was truly, despite his eccentricities, the very last of the great British explorers. We toasted his health and brazen activities late into the afternoon until, tired and worn out, we helped him into his taxi cab, knowing that he respected what The Travellers Club had done for him.

I never saw him again.