Wildlife portraiture at its best

It cannot be gainsaid that coffee-table books celebrating Sri Lanka’s wildlife riches have become an established and flourishing genre. Where did it start? G.M. Henry and W.E. Wait’s four-part Coloured Plates of the Birds of Ceylon (1927–1935) is perhaps the work I would finger as the pioneer. It wasn’t meant to be comprehensive: there were, after all, only 64 plates, representing fewer than 15 percent of the island’s species.

Besides, the artist (Henry) and the author (Wait) may have been a trifle huffed had their work been referred to as a “coffee table book”: the term came into general use only around 1960, the British until then having referred to such browse-volumes as books “to lay in the parlour window”. An extended lacuna then ensued, until in 1986 Nihal Fernando published Sri Lanka: the wild, the free, the beautiful, the country’s first photographic, predominantly-wildlife orientated coffee-table book. It is hard to know what took it so long: after all, several internationally celebrated photographers, had spent extended and productive periods in the island—Roloff Beny, H. W. Cave, Julia Margaret Cameron, W. L. H. Skeen and Lionel Wendt, to name only a few. But wildlife, it seems, didn’t weigh heavily enough on their minds.

Despite Nihal Fernando’s book quickly achieving bestseller status, the expected series of copycats failed to materialise. A few books did appear, but of uneven quality (I too, was responsible for one of these, in 1998, and freely confess I did it for the money). The advent of digital photography, however, inspired many more people to take up the art and soon the nation’s coffee tables were straining under the weight of their output. I count in my library some 30 wildlife photography books since 1986, most in the last decade. Refreshingly, Sri Lanka’s high-wire photographers adopted a diversity of distinctive styles which I—unkindly, I know—place in irreverent categories: Gehan de Silva Wijeyeratne (critters and flappers), Lalith Ekanayake (eating and being eaten), Chitral Jayatilake (all creatures great), T.S.U. de Zylva (wings and things), and so on.

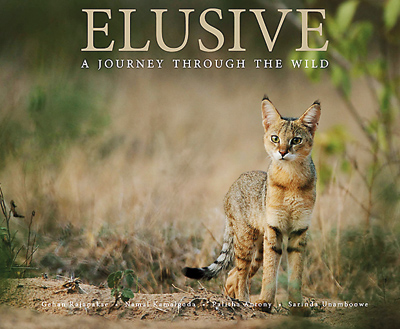

It annoys me that I can’t think of a suitably impertinent term to describe Elusive: A journey through the wild. Weighing in at around 2½ kg it is way above welterweight class, not to be handled by those who haven’t eaten their spinach. But it is a masterpiece. That was in part to be expected, of course, for its authors had previously published two successful books (Encounters in 2003 and Enchanted in 2007). Looking through those earlier works now, I see their images yet fresh, almost every one still worth publishing. But to me, Elusive appeals on an altogether higher plane. First, despite it being the work of four people, its photographs have an impressively uniform flavour. Second, it is unashamedly a book of spectacular portraits in a world in which portraiture is fast giving way to action. And finally, almost every one of Elusive’s 300 pages leaves me wondering, Wow, how the devil did they find that light?

Indeed, the photo of the jungle cat on the jacket says it all. It is an animal notoriously difficult to photograph, almost never seen in daylight. Yet there it is, staring superciliously at the camera with characteristically feline detachment, photographed at eye level, in a perfectly shadowless, warm light, the focus delicately soft, the arid pastels of the background saying more about its habitat than words ever could. And these sentiments could equally well apply to dozens of other images in the book, not least the elusive spurfowl (my favourite), which John Gould couldn’t have composed and illustrated better.

I also liked the fact that the authors have given smaller animals too, their due place. These include 10 frogs, all beautifully illustrated (I have photographed many of these species myself, though nowhere near as elegantly, so I appreciate how challenging it is) and a magnificently menacing crab. But it is the birds that take pride of place, and justifiably so, given the superb imagery and the wealth of rare species that only the most assiduous of twitchers gets to see, let alone photograph so beautifully. The venues too, are much more diverse than usual, with brilliant images from sites such as Morningside and Mannar. What is more, the authors assure us that none of the images has been ‘Photoshopped’ (digitally retouched). They don’t need to: to Photoshop these would be to gild a lily. The authors have also done well to avoid swamping the book with banal photos of elephants and leopards, and there is only a small handful of cliché-images that might have been better omitted: flamingos in flight—really? The Blue Magpies that have become de rigueur in volumes of this kind are there, of course, but shown mating: Wow!

In almost every photo the composition, colour, shadow-detail, focus and subject matter blend perfectly. And then there is the production, where superlatives fail me. Nelun Harasgama-Nadaraja has once again surpassed herself as a print designer, and Shehan de Silva (I happen to know) has done a better job of printing and binding Elusive than he’s ever done for any of my books. The cover, jacket, paper, print and inks cannot have been bettered. The authors are going to find it hard to come up with a worthy sequel: should they do so, given their mastery of illumination, might I suggest Enlightened?

Elusive is the joint work of Gehan Rajapakse, Namal Kamalgoda, Palitha Antony and Sarinda Unamboowe, friends united by their love of the wild and interest in photography (collective tippling under the stars is said to play a part, but that evidently takes second place).

Like its predecessors, Elusive is the distilled result of thousands of hours of toil, sweat and, no doubt, blood—given freely to mosquitoes and leeches. In it the wildlife coffee-table book reaches its quintessence—it seems there is nowhere left to go.

This is art in its most perfect form: not wildlife as it is, perhaps, but certainly wildlife as we would like it to be.

I would have liked to write that the book is an inspiration to all amateur photographers, giving us something to aim for and aspire to.

As I turned the last page, however, I confess my emotions weighed more toward rising envy and a distinct feeling that I no longer like these four guys. There is no point competing with them: they make me want to give my cameras to the poor and take up golf instead.

Elusive is a gobsmacker of a book that is a delight to own and to cherish. If you can’t buy a copy, this—despite its considerable heft—is definitely a book worth stealing.