Sunday Times 2

Cyclones: Sri Lanka’s underrated hazard

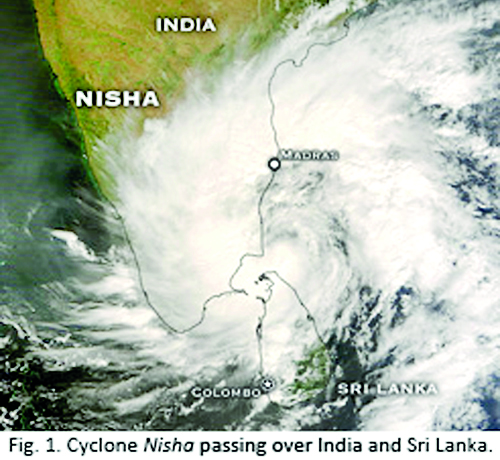

The recent devastation in the Philippines due to Typhoon ‘Haiyan’ once again reminded us of the threat of powerful storms in the tropics. Such rotating weather systems are called typhoons in Northwestern Pacific, ‘hurricanes’ in North Atlantic and Northeastern Pacific, and ‘cyclones’ in Indian Ocean Region and South Pacific. A satellite image of the tropical cyclone Nisha as it passed over South India and Sri Lanka in November 2008 is shown in Figure-1. The purpose of this article is to raise public awareness of the threat of cyclone-induced sea surges causing tsunami-like flooding in coastal areas.

Sri Lanka is vulnerable to cyclones generated mostly in the Bay of Bengal, and to a lesser extent, in the Arabian Sea (see the map in Figure-2). Some of the cyclones that form at low latitudes in the Bay of Bengal move west or west-to-northwest into the Gulf of Mannar across Sri Lanka. On the other hand, a few of the cyclones that form in Southern Arabian Sea could also make landfall in the west coast of Sri Lanka. November and December are the most cyclone-prone months for Sri Lanka.

Sri Lanka is vulnerable to cyclones generated mostly in the Bay of Bengal, and to a lesser extent, in the Arabian Sea (see the map in Figure-2). Some of the cyclones that form at low latitudes in the Bay of Bengal move west or west-to-northwest into the Gulf of Mannar across Sri Lanka. On the other hand, a few of the cyclones that form in Southern Arabian Sea could also make landfall in the west coast of Sri Lanka. November and December are the most cyclone-prone months for Sri Lanka.

Cyclone induced storm surges

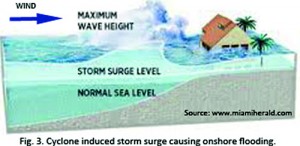

Together with extreme winds, heavy rainfall and sea surge, land-falling cyclones, typhoons and hurricanes often cause immense death and destruction in vulnerable coasts. Usually, much of the death toll and damage to property in coastal areas is as a result of cyclone-induced storm surge (‘sea surge’) causing flooding of low-lying coastal lands (see Figure-3) as was evident in the aftermath of the recent disaster in the Philippines.

Storm surge is a rise of sea level caused mainly by pushing and consequent piling up of water against a coast under the action of high winds like those due to cyclones. The low pressure accompanying a cyclone also helps raise the sea water level further. The worst impacts occur when the storm surge arrives on top of a high tide. Waves generated by the powerful winds also contribute to a higher sea level.

The height of the storm surge depends on cyclone characteristics such as the wind speed, the pressure drop, the angle with which the cyclone crosses the coast as well as on the shape of the sea floor and the coastline. The surge of water so generated by the cyclone induced wind then rushes inland causing flooding. The severity and the extent of flooding depend primarily upon the surge height and the prevailing tide as well as the elevation, the slope and the roughness of the terrain.

Owing to the dense population of the region, 26 of the world’s 35 deadliest tropical cyclones have occurred in the Bay of Bengal. A 10-metre high surge due to the Great Bhola Cyclone of 1970 in Bangladesh caused an estimated death toll of 300,000 to 550,000. Also, in Bangladesh, a cyclone in 1991 too resulted in a 6-metre high storm surge and a death toll of 138,000.

Notable past cyclones across Sri Lanka

According to the classification of revolving tropical weather systems adopted in Sri Lanka, maximum sustained wind speeds of 62 to 88 km per hour, 89 to 118 km per hour and 119 to 221 km per hour are categorised as cyclonic storms, severe cyclonic storms and very severe cyclonic storms, respectively. Sixteen cyclones, of which five are severe or very severe cyclonic storms, are known to have crossed Sri Lanka during the past 130 years. Of these, only two have been formed in the Arabian Sea and made landfall in either western or northwestern coastlines of the country; the rest have all been formed in the Bay of Bengal and made landfall on the north and east coasts.

According to the classification of revolving tropical weather systems adopted in Sri Lanka, maximum sustained wind speeds of 62 to 88 km per hour, 89 to 118 km per hour and 119 to 221 km per hour are categorised as cyclonic storms, severe cyclonic storms and very severe cyclonic storms, respectively. Sixteen cyclones, of which five are severe or very severe cyclonic storms, are known to have crossed Sri Lanka during the past 130 years. Of these, only two have been formed in the Arabian Sea and made landfall in either western or northwestern coastlines of the country; the rest have all been formed in the Bay of Bengal and made landfall on the north and east coasts.

Of the five severe cyclonic storms, the systems that developed in December, 1964 and November, 1978 appear to have caused the most notable death and destruction in Sri Lanka. Only little information is available on the impact in terms of number of casualties and damage to property due to the severe cyclonic storms that crossed Sri Lanka in 1907, 1922 and 1931.

Trincomalee cyclone of December 1964

The very severe cyclonic storm that made landfall near Trincomalee on December 23, 1964 with reported maximum wind speeds of about 215 to 240 km per hour resulted in a death toll of about 650 with 400 missing in the Northern Province, according to Dinamina newspaper of December 25, 1964. The 1964 cyclone also induced a massive storm (sea) surge of height up to about 4.5 metres (15 feet) in Mannar inundating and destroying low-lying coastal settlements and also contributing to the death toll. A detailed account of the impact of the storm surge is given in the Ceylon Daily Mirror of December 29, 1964: “A fantastic tidal wave, rising fifteen feet over the land, whipped over the island of Mannar at the very height of the awesome cyclone. Today, six days after the event, only a sheet of water, subsiding ever so slowly, marks the place where once a city stood.” The powerful storm surge due to this cyclone also overturned a passenger train running between Pamban and Dhanushkody, 30 km west of Talaimannar, killing all 150 passengers on-board.

Batticaloa cyclone of November 1978

The very severe cyclonic storm that made landfall near Batticaloa on November 24, 1978 with an estimated maximum wind speeds of 222 km per hour caused loss of lives as well as extensive damage to housing and buildings and generated a storm surge of height 1 to 2

Figure 3

metres near Batticaloa with inland penetration of inundation reaching 1.5 km in Kalkudah. The death toll attributed to this cyclone varies from 323 to 915.

The death toll due to the severe cyclonic storm that made landfall on November 12, 1992 was only 4, with over 29,000 housing units damaged. The severe cyclonic storm that crossed Sri Lanka on December26, 2000 also resulted in eight deaths and considerable property damage. In May 2003, a cyclone that did not cross Sri Lanka but moved further east, however, induced extremely heavy rainfall in some parts of Sri Lanka, resulting in about 250 to 300 deaths due to inland floods and landslides. The casualty and damage figures given above are usually due to the combined influence of one or more of the following cyclone related effects: sea surge, high winds and heavy rainfall.

Assessment of storm surge hazard for Sri Lanka

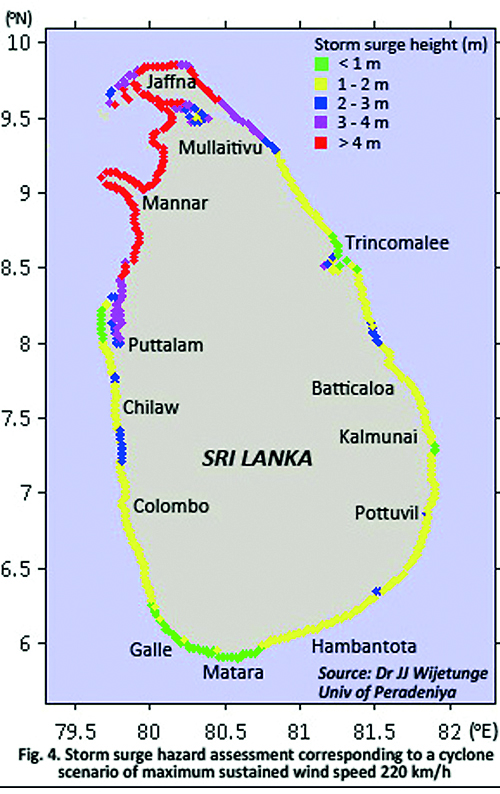

Figure- 4 shows the distribution of the storm surge heights around the coastline of Sri Lanka corresponding to a tropical cyclone of maximum sustained wind speed 220 km per hour with an estimated recurrence interval of about 100 years. This map is based on  computer simulations of a large number of different cyclone paths across the country so as to obtain the maximum surge height for each location.

computer simulations of a large number of different cyclone paths across the country so as to obtain the maximum surge height for each location.

The writer wishes to thank the Ministry of Disaster Management, the National Science Foundation and the University of Peradeniya for supporting this study.

Clearly, the northwestern and northern coastal areas of Sri Lanka are likely to experience more severe flooding caused by storm surges than the south and the west. The shallow bathymetry and the wider continental shelf fronting the north and northwest are primarily responsible for the higher level of surge heights. On the other hand, the southwestern coastal areas are exposed to a lower level of storm surge hazard. Note that, although there is a higher chance of cyclones making landfall on the eastern and northeastern coasts than the west, cyclones induce sea surges not only during approach (landfall) but whilst leaving a coastline as well.

We must remind ourselves that several severe cyclones have hit Sri Lanka in the past century, with those in 1964 and 1978 being the worst, resulting in loss of lives of the order of several hundred as well as considerable damage to housing and other infrastructure due to both the surge and the high winds. In comparison, the death toll in Sri Lanka due to the tsunami disaster in December 2004 was in the region of tens of thousands, however, a tsunami event of such magnitude is extremely rare, expected only once every several centuries.

So, tropical cyclone induced storm surges appear to pose a more frequent, albeit comparatively less severe, threat of flooding in most parts of the coastline of Sri Lanka than tsunami. Nevertheless, it must be noted that the severity of the storm surge hazard could be greater even compared to the tsunami for certain parts of the coastline of Sri Lanka. For example, the city of Mannar and the nearby localities are probably more at risk of coastal flooding due to storm surges than tsunami. So, whilst improving our tsunami preparedness in coastal areas, we must also pay due attention to the potential threat of coastal flooding due to cyclone induced storm surges as well.

How can the country prepare itself for a severe cyclone event? As far as storm surges are concerned forecasting of storms, early warning and evacuation are necessary to save lives. Furthermore, as in tsunami mitigation, public education and awareness is also an important aspect in storm surge hazard mitigation as well. So, it is prudent to integrate the tsunami hazard with cyclone induced storm surges as part of a multi-hazard risk reduction strategy.

The writer is a Senior Lecturer at the Faculty of Engineering, University of Peradeniya