News

Norochcholai: CEB in power battle to win coal war

Employees of the Lakvijaya Power Station in Norochcholai assembled in its lobby on New Year’s Day to hear speeches by the management. Chinese workers cycled to work while, in the distance, puffs of white steam rose from the generator of the coal-power plant’s first unit.

“Everyone here wants this project to succeed,” said an official, speaking into a mike. “It is true that the first phase has had some shortcomings but we have corrected many of these in the second and third units.”

Coal is piled up near the Lakvijaya power station, waiting to be crushed and burned. Pix by Nilan Maligaspe

Those units are set to be commissioned within the year. One was receiving finishing touches when the Sunday Times visited on Wednesday while the other was still at construction stage. Lakvijaya now generates 300 megawatts of power. It will eventually add 900 megawatts to the national grid.

It was just two days since the unit resumed operations after a pipe leak caused a shutdown of more than two weeks. Ever since it was commissioned in March 2011—a month before local government elections —Lakvijaya has attracted media attention for all the wrong reasons.

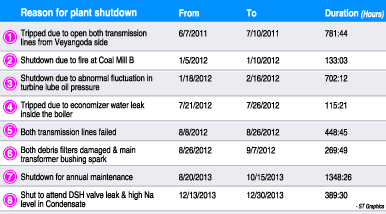

Statistics obtained by the Sunday Times show that there have been 24 interruptions to power supply since July 2011. Apart from planned shutdowns carried out for maintenance, some of these have lasted several days. Others were corrected in a few hours. Among the recorded faults are valve repairs, damage to pipes, coal mill fires, an

Cheese: Chinese workers snap a picture with the power station as backdrop

abnormal fluctuation in turbine lube oil pressure, a hydrogen seal oil leak, debris filter damages, high temperature in cooling water pumps and a failure of both transmission lines.

Tilak Siyambalapitiya, an energy sector expert, holds that the frequency of breakdowns is “really too much”. “The published value of the entire 900 megawatt project is US$ 1,380 million,” he said. “That is within international norms. But if that is within international norms, we should get an international quality power project.

But Ceylon Electricity Board Deputy General Manager (Lakvijaya Power Station) D.C.J. Saram has a different view.

Addressing workers on the New Year’s Day, he said: “When any plant starts operations, especially one as large as this, there can be a lot of breakdowns during the first two years.”

The CEB insists that the operational bar has been set higher for the next two units. Officials admit that things could have been done better in the first unit but they also recognise that some challenges were beyond their control.

The control room

In 2011, with elections around the corner, the Government had wanted the unit commissioned on an urgent basis. Many processes that should have taken a few more weeks to complete were expedited. The CEB was unable to demand the best quality of work or material from the contractor by, for instance, delaying payments.

“There was tremendous pressure from the Government to speed this up,” said one authoritative source, requesting anonymity. “When we commission a plant and connect it to the power system, we have to do a lot of testing. But when we accelerate the process, we tend to omit small procedures. Sometimes, even a small problem can trip a plant. Expediting the first unit has caused some lapses.”

Having learnt a lesson from this, the CEB is delaying the commissioning of the second unit until everything is ready. It was initially scheduled to be inaugurated in early January. It is still set to open this month but no date has been set.

Officials say they are closely monitoring the building of the new units. Having identified certain mechanical weaknesses or unsuitability of parts in the first unit, the CEB has demanded changes from the Chinese contractors.

For instance, when it was found that a design flaw was causing frequent breakages in a filter that separated debris from sea water, the CEB asked the company to use a different one in the next two units. “We have made many other alterations after gaining experience,” said an electrical engineer on site.

In his New Year’s Day speech, a Lakvijaya manager confessed that it hadn’t always been easy getting the same contractor and subcontractor to do things differently.

In his New Year’s Day speech, a Lakvijaya manager confessed that it hadn’t always been easy getting the same contractor and subcontractor to do things differently.

Another CEB employee told the Sunday Times that the power plant would have been of higher quality had it been European, German, Japanese or American.

“The materials they use and their safety measures are a little more reliable but, again, at a cost,” he explained. “The Chinese plant was the only one offered at the time. They were the saviours.”

Running Lakvijaya smoothly is complicated by the fact that it is such a large plant with many auxiliary components. The scale of the operation is vast and complex. We walked under hundreds of pipes of different lengths and widths, on grills installed above tunnels containing more pipes and machinery, through passages and up staircases to where the turbines and generators are, alongside conveyor belts and around towers.

We saw fans and motors, instruments and pumps. There are coal crushers, boiler steam pumps and the flue gas stack with its distinctive red stripes. An engineer opened a small window on a pipe to show intense orange flames inside. Caused by the burning of pulverised coal, the light could not be looked at with the naked eye. In the control room, four people on shift watch computer screens all the time as thousands of sensors record vital information. The types of damages that need to be fixed are also complex.

The plant was last shut down when just one of 16,000 narrow pipes carrying sea water for cooling purposes sprung a leak. The pipes are located inside metal towers with just two openings. Each pipe had to be searched with the use of electric lights. Fans were used to provide some air to engineers that climbed into the tower. The fault was finally located with ultrasound scanners imported by the Chinese contractors.

On another occasion, when the level of sea water used for cooling suddenly dropped, the management deployed divers to check the underground channel. The walls of the tunnel were encrusted with shellfish and this was hindering the flow. It took many days for them to dislodge and manually remove the critters so that they would not clog any more systems.

Recently, one of the conveyor belts that transport coal from barges to the yard sustained damage. “Everyone worked hard amidst the coal dust to have it fixed in just two days,” CEB’s Deputy General Manager Saram said in his speech. “Two (coal) ships were parked here. We have to pay Rs. 5 million per day per ship in late fees. And when one of our condensers broke down, people dedicated themselves day and night to repairing it.”

There are other issues, although Lakvijaya officials were less forthcoming with information. All instruction manuals for the power plant had been in Chinese. While some of these have now been translated, many of the documents pertaining to auxiliary parts are still in Chinese. This is a massive drawback.

Meanwhile, the warranty period for many of the parts in unit one is over. When parts are damaged — as they frequently are —the Chinese contractor is no longer bound to meet the replacement cost.

There are also concerns about distribution. Fishermen in Puttalam have blocked the construction of a high tension power line across the lagoon to supply electricity from the second phase. With the commissioning of the second unit, there will be 600 megawatts of power available for the national grid. If the existing transmission lines are given heavier burdens, tripping could result in countrywide blackouts, an engineer said.

But Mr. Saram brushed off these fears. He said that construction of a substation in Chilaw will soon be complete, and that the extra load can be accommodated. “There are solutions,” he added. “We can reduce the capacity of both plants and feed or we can de-load one unit and run the second unit to full capacity. We can definitely feed 450 megawatts of power.”

Mr. Saram says criticism of Lakvijaya is unfair. The CEB fought a long battle to have the power station built. In the two years and nine months since its commissioning, it has saved the country at least US$ 500 million in foreign exchange. The government would otherwise have spent that money on diesel to generate power.