A timeless journey

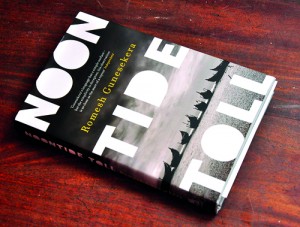

“When we first heard the war was over, we believed a line could be drawn between the mistakes of the past and the promise of the future. One was the place you had been, the other was the place you were going to. We believed there was no need for the two to be connected. But as a driver, I should have known better. To go from one to the other, you need a road. And a road is nothing if it doesn’t connect,” muses Vasantha, in Romesh Gunesekera’s Noon Tide Toll. Fresh from the Jaipur Literature Festival and briefly in Colombo to launch his new book, Romesh Gunesekera takes us through his latest work.

Noon Tide Toll is divided into two main sections – north and south – with short stories that can be read in isolation or as a novel in their entirety. The common strand running through these stories is its narrator. We see an innocuous figure usually relegated to the

Romesh Gunesekera in Colombo. Pic by Mangala Weerasekera

background, firmly placed in the foreground. Vasantha retired early, bought himself a van and now transports a plethora of colourful characters around the island.

There’s a curious abstruseness which surrounds Vasantha. The van driver grew up in a shack near a cemetery in Colombo, has little or no education but reads TIME magazine, Readers Digest and watches Channel 4, Al-Jazeera and BBC world. “In his [Vasantha’s] case, he is self-educated to some extent but he achieves a level which I hope is just plausible enough. He doesn’t necessarily read lots of books but he is aware of the world around him,” says Romesh, explaining that he wanted to challenge the stereotype. “I tried as hard as I could without overdoing it, to suggest that your background is important and particularly in a place like Sri Lanka, people tend to assume that your background determines everything about you. And that’s not true in real life. People manage to find a greater sense of themselves than what they were given when they were born and I was just aware (and this again goes back to some of my earlier books as well) that you can come from impoverished backgrounds but that doesn’t mean that all doors are closed to you.”

He explains that using Vasantha as a linking device through the stories, started off purely as an experiment. Soon, the author found he liked the van driver’s company and began to develop it further and the result was a “two-sided book”.

The ‘van man’ has some remarkably introspective reflections (“You need to check your rear-view mirror, but you can’t be looking back all the time–not unless you are in permanent reverse”) and moments of wry humour (“Dilshan had credentials bursting out of his biceps”) as he takes us from Point Pedro to Dondra through verbal vignettes of the places he visits and the people he ferries. The assorted characters which traipse in and out of the stories range from the tactless, talkative Mrs. Cooray who is almost a caricature (“The war is not heritage, Paul. The priority is tourism”); a hospitable Army Major with immaculate hands (“Politics is not my expertise. I do not try to predict the future. I am a solider. I do what I am commanded to do”), faint echoes of a modern Leonard and Virginia Woolf and the sphinx-like Saraswati.

Memory, history and the politics of selectively remembering and forgetting are leitmotifs scattered through the novel. The stories are rooted in a post 2009 space and time and Romesh deals with issues such as making peace with the past and the reluctance to acknowledge it. He says: “What happens in the past just doesn’t go away. People in England for example are still writing about the First World War. These things are part of one’s history and you can’t erase it without actually amputating some part of your own story”. While in semantics the ‘post-war’ label is one that cannot be shed easily (everything from now on is post-war after all) and it specifies a  moment in time, Romesh mused that it is likely that “the concerns of what happened before the war period will get diluted or dissipate or people will forget about it and move on”.

moment in time, Romesh mused that it is likely that “the concerns of what happened before the war period will get diluted or dissipate or people will forget about it and move on”.

Is the distance away from Sri Lanka, while still writing about Sri Lanka, a boon or a bane? “For me distance is important. It has become important,” replies Romesh who is based in the UK, “though in fact with all my books, some part of it has been written here in Sri Lanka. At some point the words are being read here because I wanted to feel that it still makes sense, if you know what I mean”.

The book also deals with problematic black and white dichotomies. The double bind of the soldiers is depicted -‘If things go right, you are seen as smart; if they go wrong, then you are called reckless’ – as well as the humanization of the ‘other’ through various back-stories. Faceless statistics and figures are given faces, families and narratives. The dilemma of the diaspora and their restless feeling of dislocation as well as older scars such as the tsunami are also dealt with. The van Vasantha drives becomes a sanctum for its passengers (“A place of safety. An island of peace” in the driver’s own words) and the road and journey is used as an extended metaphor for the past and the future. Throughout the book we are also reminded that “Big mistakes make big history”.

“The books are meant to be timeless and are not time bound and I believe that very much,” smiles Romesh. “At the same time there are moments in time when you have different resonances. This book has a certain resonance now because of the moment we are in and in five years’ time it will have a completely different resonance because other things would have happened and the world we live in and the world that readers live in would have changed so much.”

Noon Tide Toll is available at the Barefoot Bookshop and other bookstores priced at Rs. 1000