Trapped for tourists

There has been much hype in the media about an albino turtle that was supposedly stolen from a commercial hatchery that caters mainly to tourists. In the interest of conserving our natural resources, in this case turtles, it is necessary to focus our attention on these commercial hatcheries and the impact of their activities on the turtles itself.

Following a court order the Dehiwela Zoo recently received four live albino turtles and the dead albino turtle found in a turtle hatchery. The babies had just hatched and the other two are six kg and three kg. All these turtles including the dead one, are not true albinos though they were white and looked like albinos. These turtles have melamine in their bodies and have black eyes which show that they are not true albinos.

A very recent newspaper report says that the police had discovered a turtle slaughter house in Negombo. The price per kilo of flesh sold surreptitiously to selected customers is Rs.1,500. This illicit den has been in operation for about eight months and has seen the slaughter of over 100 turtles.

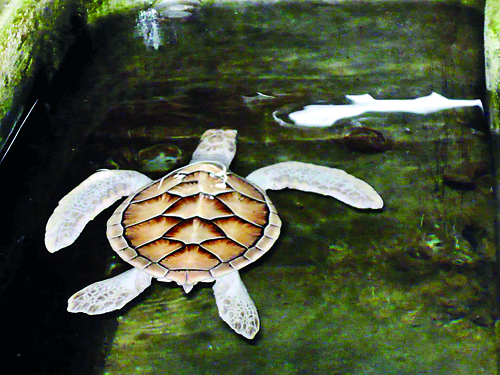

Commercial venture: Many hatcheries along the coast keep turtles in cement tanks

In earlier times turtle flesh was sold in the most gruesome manner in coastal markets. Since turtle flesh putrefies fast, the turtle is not killed but the vendor cuts off portions of flesh, in quantities needed by the customers. It was therefore not unusual to see, in these market places, turtles on their back with gaping holes in their bodies, still alive and weakly moving their flippers about. I have seen this happen in the Chilaw market many years ago. Now the sale of turtle flesh is not carried out in the open.

I was in Chilaw again last week and even then I heard of a place, not known to many, where turtle flesh was sold surreptitiously. The turtles were brought in by fishermen who initially had accidentally caught them whilst netting fish. Now it seems that, since turtle flesh has a demand, turtles are deliberately caught.

With such illegal sales of turtle flesh up and down the coast, there is a threat to the turtle populations visiting our shores. Sri Lanka sees five of the seven species in the world breeding here. They are the Green turtle (Chelonia mydas) (S: Kola kesbewa or Weli kesbewa), Hawksbill turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata) (S: Leli kesbewa or Pothu kesbewa), Olive Ridley (Lepidochelys olivacea) (S: Mada kesbewa or Batu kesbewa), Loggerhead (Caretta caretta) (S: Olugedi kesbewa) and Leatherback (Dermochelys coriacea) (S: Dara kesbewa). The sea turtles are called Kadal Amai in Tamil.

It is known that the flesh of the Leatherback turtle can cause seafood poisoning. Its main diet of jelly fish can cause this build up of the poison called chelonitoxism in its body. However only a small number of this species come ashore here.

In earlier times when there was no turtle conservation consciousness, turtle flesh served on small pieces of turtle shell, was a delicacy at fashionable weddings in the south of Sri Lanka. Turtle shells were used to make ornate head combs for both ladies and gentlemen in earlier times, trinket boxes, spectacle frames etc.

Turtles visit our beaches right round the year but the numbers increase significantly in December and January. The small number of Leatherbacks come ashore in August and September.

In their natural state female turtles come back ashore to the beaches where they were hatched to lay their eggs. It is important to understand how these turtles come back to the beach of their birth. The female turtle crawls up the beach and turns round to face the sea. Having done so it proceeds to dig a hole with its back flippers. Most times the female digs a number of holes and covers them up in an attempt to deceive predators, both human and animal, who try to raid her eggs.

Around 100-120 eggs are laid. The Green turtle lays around 150 eggs. The soft-shelled eggs are the size of and look like ping pong balls. The hole in which the eggs are laid is covered with sand and stamped down. The female straddles the nest hole and raising herself to her full height drops down thus firmly stamping the hole.

After about 60 days the eggs hatch out at night and the baby turtles dig themselves out and, guided by the stars on the horizon and probably the sound of the sea, move as fast as they can towards the water. On their way they are at the mercy of human predators, dogs, jackals, monitor lizards, gulls and crows. The hatchlings that make it to the sea are then preyed on by the fish in the shallow parts of the sea. Of the baby turtles that hatch out only a small percentage survive.

The hatchlings, in their movement from the beach to the sea, get an imprint in their brain, which helps the females, many years later, to find their way back to the beach where they were born. This ‘GPS’ guide is very important since they must come back to a suitable beach to lay their eggs.

The Turtle Conservation Project (TCP) which was started in 1993 is an asset to turtle conservation in Sri Lanka. The aims of the TCP are to devise and facilitate the implementation of sustainable marine turtle conservation strategies through education, research and community participation. There are also turtle hatcheries along the coast road purportedly set up to conserve turtles. These are however commercial ventures where some turtles are kept in cement tanks. Unfortunately the effort that the department made at conserving the turtles that come onto the beaches at Bundala has collapsed. The results of this venture are veiled in secrecy. Another example of the disinterest, apathy and indolence of the department.

Under the Fauna and Flora Protection Ordinance, it is an offence to kill, wound, harm or keep a turtle in possession, sell or expose for sale any part of a turtle, or to destroy or take turtle eggs. The turtle hatcheries are illegal unless approved by the Department of Wildlife Conservation. In the interests of true turtle conservation the department should not allow turtle hatcheries to operate. The department’s mandate is to conserve the turtles and not encourage their exploitation by commercial interests under the guise of turtle conservation. The Director General of Wildlife can authorise turtle hatcheries to be operated, under the existing legislation, for the purpose of conservation and research. However these hatcheries, if run scientifically, cannot make a profit, since the hatchlings have to be allowed to get into the seas soon after hatching and not be kept back for exhibition and demonstration purposes.