Sunday Times 2

Pauline de Croos case: A verdict in dispute

On 7-February, 1966, 11-year-old Ramdas Gotabhaya Kirambakanda disappeared.

On the following day, his body was removed from a well within the precincts of St. Rita’s church on St. Rita’s Road, Mount Lavinia. Thus began a sensational crime investigation which rocked the island, four decades ago.

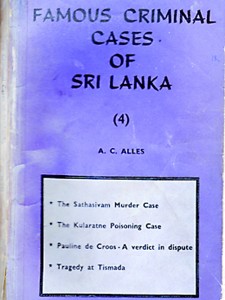

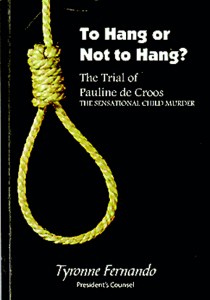

Former Justice A.C. Alles, in his Famous Criminal Cases of Sri Lanka series in Vol. 4 (Sep-1980), recounts the ramifications of this murder. Advocate Tyronne Fernando, assigned counsel for Pauline de Croos in the Supreme Court, in his book To Hang or Not to Hang — The Trial of Pauline de Croos (1973/revised ed. 2007) describes the case in 70-pages. Former Observer Crime reporter Kirthie Abeyesekara in his initial opus Among My Souvenirs (1990) touches lightly on his interactions with Pauline, her poetry and letters.

Pauline de Croos, now domiciled in Australia, was sentenced to death on March 7, 1968, at age 22, for the murder of Gota, by Chief Justice H.N.G. Fernando in the Supreme Court of Sri Lanka, after an English-speaking Jury’s verdict of 6-1 was brought against her.

The three-member Court of Criminal Appeal comprising Justices T.S. Fernando, HW. Thambiah and A.L.S. Sirimanne dismissed her

|

|

| AC Alles and Tyronne Fernando in their book deal extensively with the case | |

appeal on May 24, 1968, by a majority decision, the dissenting judge Sirimanne recommending a retrial. (1968: 71-NLR-169.) Senior Crown Counsel V.S.A. Pullenayagam with Crown Counsel Kenneth Seneviratne and L.D. Guruswamy appeared for the Crown.

The prosecution, led by the dynamic Senior Crown Counsel A.C. (Bunty) de Zoysa and Crown Counsel Kenneth Seneviratne, proved the case against her on circumstantial evidence. No one saw her push the boy into that well. However, all other attendant evidence and eye witnesses of her presence at crucial locations and her disastrous act of throwing away the boy’s school bag with his sandals in it pointed towards her complicity in this insensate crime.

If she had taken the bold stand of being examined and cross examined in the dock and came out clean on her part of this dastardly crime, she may have stood a solid chance of having been discharged. Such a stand was taken by the fifth accused in the SWRD Bandaranaike assassination trial — Police Inspector Newton Perera, who was discharged by a nerve-wrenching 5-2 verdict after the Jury was requested to re-consider its initial verdict of 4-3 in his favour.

The feeble and futile attempt taken by defence counsel Advocates Lucian Jayatileke and Y.G.S. Perera of mistaken identity proved a disaster in the midst of solid circumstantial evidence. Alles states that, “To challenge the evidence of one identifying witness is a gamble, to challenge two such witnesses is courting grave disaster, but to challenge the identification of ten witnesses, particularly when the person to be identified wears distinctive clothes and sports a particular hairstyle, is suicidal.”

The boy’s father Don Bodhipala Kirambakanda was discharged on March 01, 1968, through the efforts of his counsel George E Chitty, backed by five advocates: A.M. Coomaraswamy, Anil Obeysekera, Nihal Jayawickrema, V.E. Selvarajah and Kumar Amarasekera, as there was no prima facie evidence against him. However, at the end of the trial in the last line of her statement from the dock before she was sentenced to death Pauline said, “The person who is guilty you have acquitted…” A stunning revelation but far too late.

On October 17, 1968, leave to appeal to the Privy Council in London was refused by Lord Justice Diplock, wherein Sir Dingle Foot (who appeared for Ven. Talduwe Somarama in the Bandaranaike trial which began on February 22, 1961) with L.J. Blom Cooper, M.I. Hamavi Haniffa and Sherene Obeysekera, instructed by T.L. Wilson & Co. appeared for Pauline. E.F.N. Gratiaen with R.K. Handoo instructed by Hatchett Jones & Co. appeared for the Crown.

Despite both the judge and crown counsel recommending that Pauline be hanged, Governor General William Gopallawa took the extraordinary decision of commuting Pauline’s death sentence to one of rigorous imprisonment. It was an era when convicts were hanged in Ceylon.

On the contrary, one observes the verdict on September 4, 1982, of a Sinhala-speaking jury of 6-0 in favour of Rohini Dias and her chauffeur Nimal Fonseka being discharged in the murder of Chandrasekara Dias on August 30, 1979 after a phalanx of circumstantial evidence was brought against both accused.

Pauline was released from prison in 1980 having served 14-years since her arrest by the CID on 2 June 1966.

At a discussion with A.C. Alles in his home in the 1990s, he told this writer he regretted not having entertained Pauline after her release, when she had come to meet him at his home.

Perhaps she may have read his account of her case published in that year. Perhaps that missed conversation may probably have elicited much more of the truth than which surfaced at the trial. For whatever, reason Pauline visited, she could still say it now.

As Alles concludes his account of this case: “In Sri Lanka we have no provision similar to the Criminal Evidence Act of 1968, and it is still open to the public to challenge the verdict of our courts, provided it is done within the permitted limits of propriety and without transgressing the provisions of the law. It is for that reason that a review of the facts in the case of Pauline de Croos is permissible to consider whether there has been a miscarriage of justice in her case.”

firozesameer@gmail.com