A rich read on a majestic animal

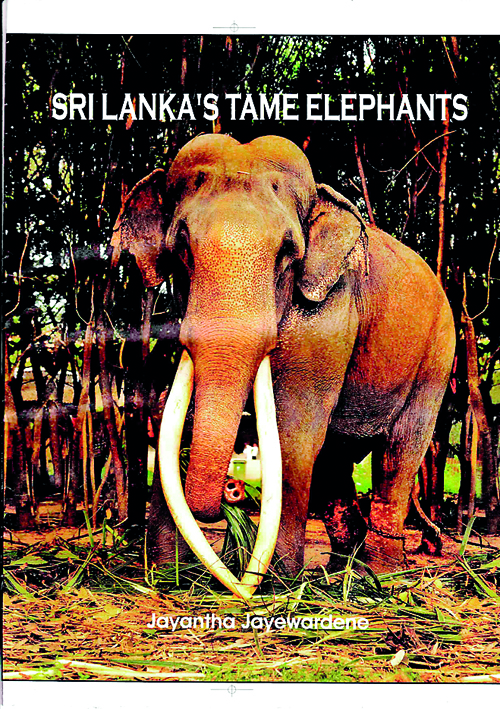

View(s):When we talk about elephants, more often than not we refer to wild elephants. We read about wild elephants and we discuss their future but seldom do we talk about tame elephants. We do talk about Raja carrying the Sri Dalada and we count the number of elephants walking in the Dalada Perahera or the Bellanwila and Gangaramaya peraheras.Now Jayantha Jayewardene, an authority on elephants has taken up the subject. ‘Sri Lanka’s tame elephants’ is the title of his latest publication.

The book kicks off with the history and legends associated with the Ceylon elephant which Jayewardene had done much research on. Stating that the elephant has been associated with the inhabitants of Sri Lanka from the Pre- Christian era dating back to even more than 5,000 years, he identifies the first archaeological record on the relationship of man and elephant to the 1st Century BC Navalar Kulam inscription in PamamPattu in the Eastern Province. The carvings of the elephant in different forms in the ancient ruins endorse the close association between man and elephant.

The elephant played a prominent role during the time of the Sinhalese kings. There is reference to the ‘mangalahatti’ – the state elephant on which the king rode – in Sinhala literature of the 3rd Century BC.

He refers to the kings capturing and taming elephants and states that the methods of capture were refined and modified as time went on. Elephants were used on all important ceremonial occasions especially where pomp and pageantry were required.

Referring to the gifting of elephants by Sinhala kings to their counterparts in friendly countries, Jayewardene says that the best elephants, presumably all tuskers, were selected for gifting. He also mentions that elephants were traded with other countries where they had been used for war and ceremonial occasions. From the earliest times there had been a significant demand for the export of Lankan elephants from other countries. Tennent (1861) says that the export of elephants from Ceylon to India had been going on without interruption from the time of the first Punic War. India wanted them for use as war elephants, Myanmar as a tribute from ancient kings and Egypt probably for both war and ceremonial occasions. There is evidence of elephants being exported to Kalinga by special boats from about 200 BB from the port of Mantai which was a major port in ancient Sri Lanka.

The author reveals that Sri Lanka had earned a reputation for skilled elephant management. The Sinhala kings had special elephant trainers. They were “kuruwe” people from Kegalle. Even mahouts had been trained by them. They had used a brass model of an elephant with a number of movable parts to train the mahouts.

As for the uses of elephants, he points out that they were used in the kings’ armies, elephant fights and for the execution of criminals. They were also used for religious purposes like ‘peraheras’, and agricultural purposes such as clearing and ploughing, as beasts of burden engaged in heavy work, as an item of trade, as gifts, in some sports and for recreational purposes.

Jayewardene also discusses the role elephants played in war. Elephants were one of the four major armies – ‘chaturanganisena’ which comprised elephants (‘ath’), horses (‘as’), chariots (‘riya’) and infantry (‘paabala’). Up to the Kandyan period, the elephants had been used for purposes similar to a heavy armoured vehicle in the modern context. He reckons that metal, leather or cloth protected the bodies of the elephants. He refers to the Dambulla Vihare painting of the tussle between Dutugemunu and Elara in the 2nd Century BC portraying the royal elephants of the two kings.

He makes the point that although there were tens of thousands of elephants all over the country during the time of the Sinhala kings, the animal was afforded complete protection by royal decree. “Accordingly the elephant could not be captured, killed or maimed without the king’s authority. All offenders were punished by death,” he states. He compares the situation today thus: “Unlike today the cultivators of that time could not plead that the animals were harmed in the protection of their crops. Any depredation or damage to crops by wild elephants had to be prevented by stout fencing together with organised and effective watching by the farmers. It is interesting to note that there were many more elephants then than now, but still Sri Lanka was considered the granary of the East.”

Jayewardene moves on to discuss the capture, taming and training in detail followed by management, work, food, health and many more topics related to tame elephants. He details the clauses of the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Ordinance.

Talking about ownership of tame elephants, he has found that during the time of the British the first owners were the chieftains of the Wanni district. They were either given or allowed to keep some wild elephants. The chieftains had to give a specific number of elephants each year as tribute to the British government. Many elephants were captured by the kraal (‘athgaala’) method when a herd of elephants are driven into a large enclosure (‘gaala’) and then captured. As for the capture of elephants, Jayewardene outlines several methods: Using a female decoy, noosing – head noose, tree noose & ground nooses – druged food (opium introduced to pumpkins & melon and placed on their trail), pitfalls and kraal.

In a survey he had done in 1997, he found the largest number of elephants (11 with four tuskers) belonged to the Dalada Maligawa followed by Gangaramaya, Hunupitiya (five). He lists out owners on a province by province basis. Among them are several temples and devales.

Jayantha Jayewardene’s is a comprehensive study detailing every aspect related to tame elephants.

In the last of the 12 chapters, he discusses the future of tame elephants in Sri Lanka and laments that although it has been an association between man and elephant from time immemorial, no effort had been made to conserve the tame elephants. No laws have been promulgated to ensure protection for them. No proper breeding programmes have been initiated. The capture of wild elephants has been banned. All this leads to the depletion of tame elephants in the country.

He emphasises the need for a carefully thought out set of conditions if elephants are to be given away from the Pinnawela orphanage. Here he highlights the need to establish that the prospective owner has the finances and management expertise to bring up an elephant. He should also be able to afford to provide for the animal to earn its keep since it is now difficult to find work for an elephant.

He stresses that experience in elephant keeping is absolutely necessary. Otherwise it is likely that a dangerous and perhaps fatal situation could develop if inexperienced owners or mahouts handle elephants, he says. Quoting one example, he describes how a new rich gem merchant purchased a pregnant female elephant that was captured in the jungle and when the baby was born, the thrilled owner took the little one in the back of his jeep. One day when the vehicle jerked to a stop, the animal fell off, hit its head and died.

Jayewardene winds up by giving several strategies to be adopted in order to ensure that the tame elephant population in Sri Lanka does not diminish.

The well-illustrated ‘Sri Lanka’s Tame Elephants’ does not merely relate their story but is an educational and training manual as well. And his valuable and practical suggestions are worthy of consideration by the authorities and animal lovers.

| Book facts

‘Sri Lanka’s tame elephants’-by Jayantha Jayewardene. Reviewed by D.C. Ranatunga |