Asoka the Buddhist convert, pilgrim and patron

For Sri Lankans, King Asoka’s name will always be associated with the formal introduction of Buddhism to the island nation. But for historian Professor Nayanjot Lahiri, a keen student of the life of the third emperor of the Mauryan dynasty that ruled India between 332 B.C to 185 B.C., there are many fascinating aspects to the life of Asoka whose influence not only embraced the whole of India but also spread beyond its shore.

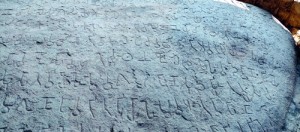

Brahmagiri: One of the many Asoka stone inscriptions found in India

“First and foremost for me, Asoka was a communicator par excellence,” says Professor Lahiri who was in Colombo recently to deliver several lectures including one on the theme “Asoka: Interweaving Archaeology with the Emperor’s Story”. And communicate Asoka did, by way of stone inscriptions that he put up across India to convey messages to his people, through which historians have been able to learn much about Asoka who ruled from 269 B.C. to 232 B.C.

These edicts, however comprehensive, reveal little about the personal aspects of the life of Asoka. “He (Asoka) was very reticent about his family life. He did not mention his mother, his grandfather (Chandragupta – the founder of the Mauryan Empire) or his father Bindusara in his edicts. He speaks in his inscriptions as a king not as a family man,” says Professor Lahiri who is attached to the Department of History at the University of Delhi and has spent many years piecing together the life of this Indian ruler.

The turning point in Asoka’s life comes with the carnage caused by the battle in Kalinga following which Asoka looks to the teaching of the Buddha to find salvation.“What is fascinating about the inscriptions of Asoka is that after the Battle of Kalinga, he uses the edicts to show repentance for the killings of hundreds of thousands of people during the war and states that from thereon “every victory will only be a spiritual victory.”

Prof. Lahiri says it was the most unusual case of the victor himself talking of the carnage caused by war and taking blame for it. “He is taking the blame for the misery caused by war and does not try to make any less the horrors of war. “He puts up multiple edicts across the land to apologize publicly for the battle of Kalinga. It’s akin to a modern day leader owning up to the horrors caused by war and not trying to shield the people from the real facts,” she says. Along with the repentance, Asoka also turns to Buddhism to overcome the trauma caused by the war. In the first one and half years of embracing Buddhism, Asoka admits he is not an active Buddhist but later zealously follows the Buddha’s teaching and begins to propagate it across his land and beyond India.

Insight into Emperor Asoka’s life: Prof. Nayanjot Lahiri delivering a lecture in Colombo. Pic by Nilan Maligaspe

“He was a Buddhist convert, a Buddhist pilgrim, a Buddhist patron. He set up stupas in all parts of India. Buddhism became very central to his being.”

It is at this time that Buddhism found its way to Sri Lanka through two special emissaries Asoka sent here.

“His relationship with Devanampiyatissa was of special importance which is why Asoka sent his children here. In his inscriptions Tāmraparṇī (Tambapanni) is mentioned as one of the lands where he sends emissaries. The fact that he did not mention the journey of his children from India to Sri Lanka is natural but it’s not that it did not happen. That was Asoka’s temperament, he was individualistic, explains Prof. Lahiri. Much of this relationship between Asoka and Devanampiyatissa and the introduction of Buddhism including the coming of Mahinda and Sangamitta Professor Lahiri says is recorded in the Sri Lankan chronicles.

Along with his growing faith in Buddhism, Asoka also sets rules for Buddhists to follow to ensure unity among followers, prohibiting division within the clergy, prohibiting the killing of animals on certain days and even making environmental legislation so that people would learn to live in harmony with nature.

“He used to put up the same message in multiple places. He wanted to be heard by the people, his voice giving the same message to people living in different places. He did not deal with his people sitting in his capital of Pataliputra like his predecessor. It is his voice you hear through his inscriptions.”

But all of Asoka‘s life was not rosy, says Professor Lahiri. The aspects of his life before the battle of Kalinga are obscure and there are no inscriptions to say what kind of life he led prior to that. “We know very little of his early years. He was not the eldest son of his father King Bindusara and he may have killed many of his brothers to become king.”

Prof. Lahiri says she has not only learned a lot through her study of the life of Asoka, but it has “elevated me as a human being.” “When you read good literature of Shakespeare or about the life of the (Mahatma) Gandhi and the Buddha, you feel elevated as a person. It is the same thing when you do research on the life of Asoka,” she says.

Prof. Nayanjot Lahiri is the author of several books including Pre- Ahom Assam (1991), The Archaeology of Indian Trade Routes (1992), The Decline and Fall of the Indus Civilization (edited;2000), Finding Forgotten Cities (2005) and Marshalling the Past (2012).

She was awarded the Infosys Prize for Humanities – Archaeology in 2013 for, as the citation stated, ‘her outstanding contribution towards the integration of archaeological knowledge with the historical understanding of India from the earliest times’.