‘Making history’ around Colombo

One of my favourite things about art is watching people instinctively responding and reacting to it. “It reminds me of scoliosis” remarks a gentleman, scrutinizing Sunil Sigdel’s installation with a medical eye. The installation made of used workers’ gloves, examines the consequences of a civil war in Nepal and the medical condition fits in nicely to depict the political and economic warping of a country’s backbone.

At another location, a husband and wife pore over the cartography and dissect power-politics in Pala Pothupitiya’s work while their two small sons bemusedly examine Mahbubur Rahman’s formidable mannequins whose leather visage is constructed out of used army boots. Thor McIntyre-Burnie’s sound installation inspired by the Weliveriya water riots brings in a social media component to art and I watch as people curiously interact with the installation listening to archived tweets about the riots.

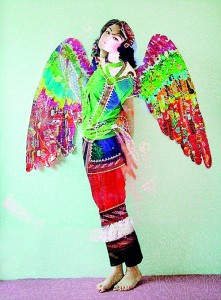

Iranian artist Hojat Amani: Angelic touch to human worldliness

During my art wanderings this week, I’m reminded of a quote in Tolstoy’s essay on art. It sounds awfully pompous to quote Tolstoy but bear with me – “It [art] is not, as the aesthetical physiologists say, a game in which man lets off his excess of stored-up energy; it is not the expression of man’s emotions by external signs; it is not the production of pleasing objects; and, above all, it is not pleasure; but it is a means of union among men, joining them together in the same feelings”.The theme ‘Making History’, which knots the Colombo Art Biennale together, is one that lends itself to multiple interpretations. A particularly interesting take on the theme was memorialising and the act of remembering: We are quick to memorialise victories for instance, but reluctant to memorialise the losses. Questions about the construction of cultural memory, splintering absolute truths, the danger of sanitising history and providing alternate narratives to the dominant discourse were ways in which the theme was explored throughout the week.

Here’s a rather desiccated version of work by artists from 15 countries, conversations and curated walks put together by a curatorial team from India, Sri Lanka and UK. The Colombo Art Biennale concludes today and is dotted along multiple venues around Colombo.

With its title borrowed from Salman Rushdie’s essays, ‘Homelands’ is an exhibition woven around themes of personal memory, public history, identity, loss and nostalgia and has been exhibited around India, Pakistan and now, Colombo. Susan Hiller’s Last Silent Movie poignantly showcases the double bind of globalising language — where the positive effect of communities understanding each other is sharply juxtaposed with the loss of local languages. The movie features language such as Potawatomi, Border Cuna, Wampanaog, Kulkhassi and Yao Kim and other extinct or endangered languages being spoken by the last individuals who remember them and was one of the works around which the concept of the exhibition revolved around. “Language and the extermination of it, is also one of the primary tools of colonisation, as we hear/ read in this film,” says Latika Gupta, curator of the exhibition, “where English allows us to access these hidden and indeed lost histories, it also acts as a colonising force, signalling the gradual extinction of not only languages but entire cultures that express themselves through the spoken word.”

Iranian artist Hojat Amani’s foray into art was through calligraphy as Iranian and Arabic calligraphy was a large part of his cultural upbringing. Amani’s work at the Biennale showcases people photographed against a backdrop of angel wings, bringing together the worldliness of human existence and an ethereal transcendence. Quoting Rumi (“we lived in the heavens and were friends of angels…there will we once more return for that is our rightful place”), Amani believes that people have been separated from their essential

Pradeep Thalawatte’s Roadscape

goodness by things like war and racism and attempts to capture this essence at least, fleetingly. What is notable is that instead of the stereotyped pure white wings, Amani’s wings are bold, bright and rich in calligraphic detail. “Often people were serious, other times they had fun with it. Both of these stances were important for me,” says Amani, speaking about his experiences photographing his subjects. “In my country, there are many who don’t like to be photographed, especially women because of religious beliefs. But for this project, people were often eager to experience standing in front of the wings. Nevertheless, there were people that thought that they were too big to fly, and some even felt that they were too sinful to stand in front of the wings.” He explained that in some places police prevented the project because they didn’t understand the concept and thought the work was anti-religious.

As you make your way through the JDA, one of the larger venues of the Biennale, you’ll find a patchwork of sarees draped between two floors. From first sarees to homecoming sarees and with donations from Nanda Malini, Edna Sugathapala, Arundhati Shri Renganathan, Chandra Thenuwara, this 60 feet patchwork is a work-in-progress by the Fireflies Artist Network and consists of sarees donated by women across the country. Anusha Jayasinghe and Lakisha Fernando, artists from the collective, explain that plans are in the pipeline to travel across South Asia and keep adding more to their patchwork of stories.

Layla Gonaduwa explores issues such as the unquestioning acceptance of historical texts and the blind elevation to scripture as a ways and means of furthering political agenda. The Mahavamsa, she explains, has traces of Theravada prejudices as a result of the historical context it was conceived in and she uses the idea of silverfish to distort, disrupt and question this history. The theme of distortion and questioning hegemonic discourses are predominant also in Pietro Ruffo’s work. ‘Not my backyard’ features a vast US flag consisting of texts from economic and political treaties by the US and South American countries. As you edge towards the installation you see the scarab beetles carved out the paper–symbolic of the parasitic nature of the US and its manipulation of these treaties to influence the civil lives of South American countries. Speaking to the Sunday Times, the Italian artist – who asserts that every work of art is a question, not an answer – explains that his work is not to talk about a specific country, but the human habit in general. The symbol of the scarab beetle, the act of devouring and the insect’s parasitic nature could very easily be transposed to other political situations with terrifying ease.

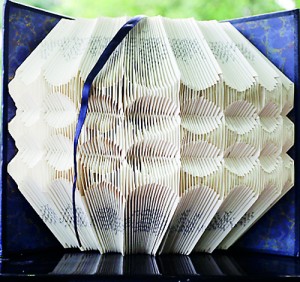

The power of paper: Indian artist Banoo Batliboi’s work. Pix by M.A. Pushpa Kumara

In a curated tour of the Lakshman Kadirgamar Institute, Indian artist Banoo Batliboi’s book sculptures raised a volley of queries from an intrigued audience. Fashioned from vintage books, Banoo renders the narrative function of the book obsolete and emphasizes its tactile quality. The metallic paper of the books, texture, its spine and cover come into focus instead of its contents. Smilingly explaining that behind every painstakingly crafted book, were many that didn’t make it, Banoo is a self-taught paper artist whose sculptures are meticulously folded instead of cut.

This year, the Biennale wrenched Colombo’s art audience out of its comfort zone, and prodded them to traipse down lesser travelled roads to discover new art-spaces and architecture in the city. When faced with a lack of one expansive space to showcase the art, the team had to get creative. The Central Point Building which houses the Museum of Economic Development, is located on Chatham Street, has tall Corinthian columns, large glass panelling and a marble interior which lends a curiously stately air to Rosemary Trockel’s lively work. The gallery inside the Post Graduate Institute of Archaeology (Bauddhaloka Mawatha) also provided an intimate backdrop for works such as Gihan Karunaratne’s artistic analysis’s on surveillance states, social media and modern mapping and Prajwal Choudhury’s installation consisting of matchstick boxes (Marilyn Manson, Shahrukh Khan, Mona Lisa and Van Gogh rub shoulders here). Tucked away in a corner of Barnes Place, the Sapumal Foundation is a haven for Sri Lankan art fans. A departure from the contemporary art exhibited at the Biennale, the pieces at the Sapumal Foundation are comfortingly steeped in nostalgia. Swanee Jayawardene, George Claessen, Lionel Wendt, George Keyt, Ivan Peries, W.J.G. Beling, Bevis Bawa, Brosius and Collette are some of the familiar names which accompany the works the rambling, old building plays host to.

The process of curating was also deconstructed in a session and humorously stripped of the grandiose notion that there is a ‘God of Art’ who magnanimously dispenses funds as and when required. Neil Butler pointed that the act of curating is in simple terms, taking a massive load of information and making it into something intelligible. It happens over a period of time, over a series of relationships, mediated by practicality and by walking a tightrope of commerce and creativity. Curator, Latika Gupta also pointed out that curating involved juggling the roles of being administrator, counsellor, banker and carpenter and being accountable and avoiding falling into the rut of unprofessional philanthropy.

The Biennale in its entirety brings about pertinent questions about the importance of arts in society, funding of the arts in Sri Lanka as well as the perceptions around it. When education is cemented solely in commerce and sciences, the arts (this is in reference to narrative, visual and performance art) is left in the periphery. This in turn, leads to a lack of resources invested in the arts, which then leads to the arts being a privilege for the privileged. Speaking to the Sunday Times, Founder and Director of CAB, Annoushka Hempel says that it’s a shame this perception persists: “It’s an interesting juxtaposition how something that is very grassroots should then be labelled as something for the privileged and the elite”. She points out that CAB is not a commercial venture and while there are a few ticketed events, the main exhibition and fringe events are free of charge,with the help of supportive sponsors and patrons, and open to everyone. Says Annoushka, “At least 50% of participating artists are from Sri Lanka and that is something we’d like to maintain as much as possible because the whole vision and mission of CAB is to create a platform for Sri Lankan artists from which they can be seen internationally and nationally.”

The discussions and live art provided fertile ground for discussion and it is lamentable that some of the events weren’t as well attended as they could have been. A festivalgoer wistfully pointed out that the Rs. 10, 000 ticket for the Colombo Bawa Tour for instance (which was part of a sponsorship event) was out of her budget. The moment you add a price tag, you immediately bracket your audience to those who can afford it but at the same time, this then goes back full circle to the questions of patronage, funding and perceptions. While funding is very much the biggest challenge, navigating the quirks of Colombo and cartwheeling through the creative chaos which comes with an event like this has its perks when the event eventually unfolds and the dialogues it creates resonate. “The Biennale is an artwork in itself,” she smiles, “it has a life of its own.”

It seems apt to leave you with an excerpt from a collaboration between Swedish artist Jesper Nordahl and other artists. Taken from a 2011 memorial built in Gothenburg, it fits in neatly into the vast jigsaw that is the Biennale:“We know that we must reshape the ground on which we live. We know that when we remember history we create another present, another social order. We know that when we remember, another world becomes possible.”