From the hearths of our Manikes, Sumiths and Baminis

Bree Hutchins can’t wait to leave the comforts of Colombo and hit the dusty roads of rural Sri Lanka to catch up with her friends in Siyambalanduwa, Kayts, Punkudutivu, Hatton, Pahalalanda and other parts of the country.

Her friends are for the most part villagers -farmers, small entrepreneurs, housewives and war widows, who gladly welcomed her into their humble homes and kitchens and shared their homespun knowledge and meals with her with a warmth and generosity of spirit that she is still overwhelmed by.

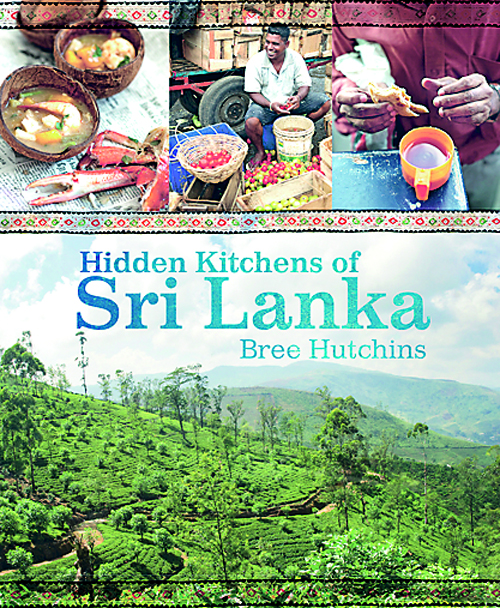

This time around, she is bringing her parents to meet them and she has another very special gift for each of them, one that will likely have them exclaiming in wonder. For now here for all to see is the food they cooked side by side with her in smoky, dimly lit kitchens, in clay pots over open fires beautifully captured in her cookbook ‘Hidden Kitchens of Sri Lanka’. Published by Murdoch Books, Australia, the coffee table book is a collection of recipes, drawn from the rural heartlands of the country, recipes that speak of the amazing diversity of Sri Lankan cuisine. These, Bree insists, are not her recipes but Manike’s and Mary’s, Sumith’s and Bamini’s and she has long anticipated the looks on their faces when she shows up with the book where they figure so large.

The book has been literally swept off the shelves in Australia, she says with unconcealed joy, though it was launched a scarce few months ago. It’s Bree’s first book and how it came about is entirely serendipitous, she feels, for her first assignment in Sri Lanka was to document the many charity projects of the Dilmah company and the MJF Charitable Foundation as a surprise gift by the family for Dilmah founder Merrill J. Fernando’s 80th birthday. With their projects encompassing the prisons in Moneragala, self-help schemes for war widows in the North and educational assistance for underprivileged kids in the capital, she found herself criss-crossing Sri Lanka, meeting the people who were the beneficiaries, seeing a side to the country that not many foreigners get to experience.

Bree discussing her book. Pic by Indika Handuwala

Qualified as a lawyer and working in a law firm that provided free legal advice, Bree had earlier virtually overnight made a snap decision to quit a profession that was almost a family tradition (her father is also a lawyer), to embrace photography and food, two latent passions. Photography was a medium she discovered to tell people stories but cooking was always there, she says- she was cooking dinner for her family at age eight! Once she had made that crucial decision she plunged in, following travel writing courses and working with established food photographers to learn the ropes. It’s all about being passionate about what you do, she smiles, “work shouldn’t feel like work.”

This way, she’s also slaking the wanderlust. In her young life Bree has an enviable litany of destinations: she’s climbed Kilimanjaro (they made the trip for her dad’s 60th birthday and the ascent “was really really hard”), travelled through the tobacco fields of Cuba on horseback, gone trekking in Rwanda to see the mountain gorillas and explored Morocco and the Greek islands, always she adds, breaking into her infectious laugh, finding her way into people’s kitchens.

Those were exotic locales by any standards but in this sunny island, she found not just the spicy cuisine so appetising, but was

Bamini prepares a Jaffna dish in her kitchen

captivated by the warmth of the people she met along the way. One blazingly hot morning on a sandy pathway in Velvettithurai, she made a chance remark to Dilmah’s Marketing Manager Spencer Manuelpillai who was accompanying that wouldn’t it be nice to put it all down- stories and recipes -in a book. His answer was a spontaneous ‘Why don’t you?’ Dilmah would sponsor her effort and back in Sydney, an editor and designer enlisted, Murdoch Books took it on.

And so within these glossy pages the reader has recipes familiar and favourite but also a glimpse into the lives of people whose stories resonate with genuine strength like Manike, the farmer’s wife and local medicine-woman in Siyambalanduwa who teaches Bree her own recipe for ‘thunapaha’and dishes like polos ambula, fried potato and brinjal moju as Bree shares their mud hut, bathing at the well, sleeping on the plank of wood that is the youngest daughter’s bed. “My dad can make the thunapaha now,” Bree says, insisting that there is great merit in making your own curry powders. She has included in the book both Manike’s thunapaha and Bamini’s Jaffna curry powder, so that both the southern and northern flavours are preserved.

The North, where Dilmah has many projects, in fact turned out to be her favourite part of the country. “It’s so beautiful, it’s also the resilience and positivity of the people like Bamini and Fr. Damien whose attitude was inspiring,” she says. Of Bamini, she writes with unreserved admiration- “She has survived bomb blasts, shellings, starvation, refugee camps, a tsunami and lost her husband one month before the war ended- most people would have just given up. But this was not an option for Bamini and that is what I love about her. With three young children to support, providing for them and giving them a good education is what matters most to her.”

Bree’s fellow adventurer on her travels was Neyome Sathyaseelan, Programme Officer of the MJF Charitable Foundation who spoke both Tamil and Sinhalese fluently and could translate with ease. Together they ventured into unknown territories, braved endless hours on the road improvising toilet stops when facilities were non-existent, and sticking it out when frustrating moments wrecked their carefully planned schedule.

It took two months of rigorous work and more. For expert though their hosts were, they were all cooking recipes passed on to them by parents and grandparents, and were ‘instinctive cooks’ who went more by the feel of things than precise weights and measures. Bree photographed every step and went back and tried and tested each one. If it didn’t look right or taste right, Neyome would be called upon to double check with the source. “It was their recipe- not my version. In one or two I would say, I like to add this,” but otherwise it’s their recipes, Bree says emphatically. The recipes came her way, she feels, because of her genuine desire to share and understand their way of life- Sinhalese, Tamil, Muslim, Buddhist, Hindu or Christian. “We didn’t rush in and rush out, we’d spend time, cooking and talking and that’s when they’d tell stories….the memories would come out. There were stories attached to dishes and family traditions.”

If Bree the cook was a perfectionist, Bree the photographer was no less. “It’s the mood I want to capture, trying to be that fly on the wall,” she grins. That as Neyome reveals, often involved Bree on dizzyingly precarious perches, making her way into workers’ quarters overlooking Sea Street and clambering out onto a nameboard just to get the right angle for a shot of the advancing chariot from the Hindu temple or balancing on a rickety crate of mangoes in Manning Market to photograph old William selling his tea to the vendors at dawn. Neyome interjects that she learned to carry a scarf with her so that when Bree tore her trousers getting them snagged in unlikely places, she would be able to provide instant cover.

‘Hidden Kitchens of Sri Lanka’ presents many recipes that Sri Lankans would consider almost rudimentary but the beauty of this book is that they come in just the way we would make them in our own homes or even in settings as surreal as Bree found in Vakarai. The MJF Foundation projects gave her access to places less visited. Learning to make pol roti within the prison walls in Moneragala was one of those experiences she captures in the book. So too the experience at the mess kitchen of the 233 Brigade: “It’s not every day that I wake up in an army camp in a foreign country. I’m in Vakarai, a small town about 60 kilometres north of Batticaloa- formerly a Tamil Tiger (LTTE) stronghold – with the 233 Brigade. Breathtakingly beautiful and serene, it’s hard to imagine that it was here, only a few years ago, that one of the bloodiest battles between the Sri Lankan Army and the Tamil Tigers took place. Strangely the Army runs a cashew nut nursery and I have come to Vakarai Camp to visit the nursery and learn how to cook cashew curry.”

The curry turns out delicious, creamy and spicy and Bree says she feels honoured it was prepared for her.

She heads for Morocco this April to spend a month trekking in the spectacular terrain of the Atlas mountains with a Berber family, of course, photographing and cooking as well. Sometime she plans to also visit Boku-Heart, the free education drop-in centre she’s launched in Freetown, Sierra Leone for ex-child soldiers and people who’ve missed out on a formal education. This project -done with four of her former lawyer colleagues- is thriving, serving a couple of hundred children and they have just had their first fund raiser back in her hometown of Sydney.

For now though, there’s a month to be enjoyed with her parents here in the country she’s found so warm and welcoming. “I’ve been adopted by so many families,” Bree says. And just maybe, find more kitchens to be visited and dishes to be discovered.

| Bree Hutchins will autograph copies of her book ‘Hidden Kitchens of Sri Lanka’ at the Dilmah t’lounge at Chatham Street, Fort on Sunday, February 23 from 3-5 p.m. The book priced at Rs.6,300 will be available at Rs. 5,000 on this occasion. |