Sunday Times 2

Little girl who lit up the darkest days

Have you ever wondered who was the greatest box-office star in Hollywood history? If you have, let me tell you this .?.?. It wasn’t Clark Gable. It wasn’t Marilyn Monroe. It wasn’t Elizabeth Taylor. And it wasn’t even Harry Potter and his amazing phantasmagorical exploits.

They all made millions in their time, but in terms of bums on seats, and hard cash in the tills, they were completely upstaged by a bright-eyed, curly-haired six-year-old tot with dimples and ringlets who saved a major Hollywood studio from financial ruin and became, in the process, the most instantly recognisable and idolised figure in the world.

The fame and charisma of Shirley Temple, who died on Monday at her home in Woodside, California, aged 85, so beguiled her own

The greatest box-office star in Hollywood history: Shirley Temple, pictured in 1936. During 1934-38, the actress appeared in more than 20 feature films and was consistantly the top US movie star. Shirley Temple Black was US Ambassador to Ghana and to Czechoslovakia (AFP)

generation, and succeeding ones, that when the news of this widowed great-grandmother’s passing flashed around the globe, even today’s children were able to sing along to her warbling of those unforgettable words: ‘On the good ship Lollipop/ It’s a sweet trip to a candy shop/ Where bon-bons play/ On the sunny beach of Peppermint Bay.’

She was a ray of sunshine during the Great Depression, a child star who provided joy and laughter for an audience desperate to escape the troubles of their everyday existence. For millions of impoverished Britons and Americans in that sepia inter-war era, she was the source of a simplistic escapism from the grind of life.

Not that she didn’t have her detractors, or those who considered her precocious charms not quite as innocent as they appeared.

At the peak of her career, Temple was the object of a devastatingly vicious attack by novelist Graham Greene, who implied in print that the sometimes suggestive manner in which she was directed, and dressed – in almost indecently short skirts, revealing an over-abundance of frilly knickers – was deliberately designed to appeal to paedophiles, and the dirty raincoat trade.

As we shall see later, this allegation was to cost Greene dear, but it was not entirely without some semblance of truth. But then, thanks to her obsessive mother, Shirley’s showbiz debut had been less than wholesome.

The saga began in the Californian resort of Santa Monica on April 23, 1928, when Shirley Jane Temple was born, the third child of George Temple, later a Californian branch bank manager, and his wife Gertrude, a thwarted dancer. Aged three, Shirley was enrolled at the Ethel Meglin Dance Studios in Hollywood, where she was spotted by two talent scouts from Educational Films, which churned out one-reel ‘Poverty Row’ shorts. Struck by the child’s winsome personality, Educational signed her for 26 short films at $50 a week – worth the equivalent of £468 in today’s money.

Eight of these were part of a sleazy series entitled Baby Burlesks, which the adult Shirley would describe as ‘a cynical exploitation of our childish innocence’ that ‘occasionally were racist or sexist’.

The regime at Educational Studios was infantile slave labour. Rehearsals meant two weeks without pay. Each film was then shot at lightning speed in two days. For playing the lead, Shirley received $10 a day.

For any child who misbehaved, there was the sinister black ‘punishment box’, containing a huge block of ice, in which the obstreperous infant would be forcibly confined to ‘cool off’. Shirley was put in this box several times.When Educational Films filed for bankruptcy, George Temple bought up his daughter’s contract for a mere $25. Aged five, Shirley’s big break arrived when the songwriter Jay Gorney, co-writer of Brother, Can You Spare A Dime?, invited her to audition at Fox Studios on December 7, 1933, for a new film, Stand Up And Cheer.

‘Sparkle, Shirley, sparkle!’ ordered her mother, and the producers were so captivated as she performed the audition song, Baby Take A

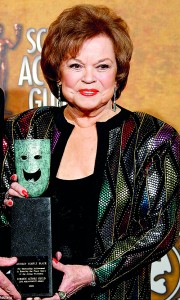

Proud: The star picked up the Screen Actors Guild Life Achievement Award just nine years ago

Bow, that she was signed up for a year at $150 a week, with an option for a further seven years, plus $25 a week for her mother. The family bandwagon was rolling.

After playing Spencer Tracy’s daughter in Now I’ll Tell, Fox loaned her out to Paramount for the lead in Little Miss Marker at $1,000 a week – six times what she was being paid by Fox.

Her co-star in that film, Adolphe Menjou, confessed: ‘This child frightens me. She knows all the tricks.’ The director got Shirley to cry on cue by telling the terrified girl her mother had been ‘kidnapped by an ugly man, all green with blood-red eyes’ – and then kept his cameras turning.

By the end of the film, Paramount knew that a star had been born, and offered Fox $50,000 – a colossal amount – to buy Temple’s contract outright. Fox, knowing it was on to a good thing, refused. Little Miss Marker became a smash-hit, packing cinemas all over America.

Now that Shirley had quadrupled her family’s income, the Temples moved to a bigger house. A full-time secretary was hired to deal with more than 4,000 fan letters a week. Business at George Temple’s bank boomed. Women queued to meet the father of Hollywood’s newest sensation. One lady even offered Temple a ‘stud fee’ to father ‘another Shirley’.

When her next film, Baby Take A Bow, premiered to massive business, President Franklin D. Roosevelt announced: ‘As long as our country has Shirley Temple, we will be all right.’ In Britain, the two young Princesses, Elizabeth and Margaret Rose, were both avid Temple fans.

Temple made eight films in 1934, including Bright Eyes, which marked her passage from stardom to superstardom. At the year’s end she was number eight in the list of the world’s top ten money-making stars. By the following year she was top of the list, and for four consecutive years she remained the world’s number one box-office star. Fox, which had owed $42?million, came out of the red entirely thanks to the whirlwind popularity of a six-year-old child.

Temple’s salary at Fox was increased more than six-fold, with her mother now receiving $250 a week. All the world’s highest-earning child actually saw of her salary was $13 a month in pocket money. Her parents were spending the rest on high living and staff.

(When, as an adult, Shirley looked for her $3,200,000 fortune – the equivalent of more than £60?million in today’s currency – she was ‘shocked’ to find only $44,000 remaining. The rest had vanished.)

Graham Greene, who had earlier referred to Temple as ‘a 50-year-old dwarf’ because of her precocity, said of her film, Wee Willie Winkie, made when she was nine: ‘Her admirers – middle-aged men and clergymen – respond to her dubious coquetry, to the sight of her well-shaped and desirable little body, packed with enormous vitality, only because the safety curtain of story and dialogue drops between their intelligence and their desire.’

Shirley Temple pictured in 1944. She could not translate her stellar success as a child star into a film career as an adult and retired from the movie industry

Twentieth Century Fox promptly sued, and Greene and his publisher had to pay £3,500 in damages to the studio and to Temple, referred to by Greene as ‘that little bitch’.

Her career faltered in 1939, when she lost the lead in The Wizard Of Oz to Judy Garland, after Fox refused to loan her to MGM. Fox rushed her into their own Technicolor fantasy, The Blue Bird, which flopped so badly it was taken off within days of opening.

Fox, realising that the party was over, let her parents buy up the remainder of her contract. Shirley’s move to MGM resulted in two further flops. A seven-year contract with David O.Selznick produced films in which Temple came across as just a typical Hollywood teenager. Attempts to extend her career into young womanhood were a disaster.

Her marriage in 1945, at 17, to film star John Agar, then a sergeant in the U.S. Army Air Force, produced one daughter, Linda, in 1948, but ended in a messy divorce, which highlighted Agar’s chronic drinking and serial infidelity. To compound the misery, Shirley made her last film in 1949. She was 21 – and washed up in Hollywood.

But she quickly bounced back. In 1950, she fell in love with California businessman Charles Alden Black, nine years her senior, who had never seen one of her films. Their son, Charles Jr., was born in 1952, and daughter, Lori, in 1954.

In 1958, Temple made a successful comeback on TV in the series, Shirley Temple’s Storybook, followed by a further series, Shirley Temple Theatre, in 1961.

She developed a strong interest in politics andin 1967 stood unsuccessfully for Congress on a ticket supporting the Vietnam War. In 1969, President Richard Nixon appointed her as U.S. representative to the 24th General Assembly of the United Nations.

Then, in 1972, she discovered a lump on her left breast which proved malignant, and underwent a mastectomy. With characteristic courage, she went public with her illness, becoming one of the first female celebrities to admit to breast cancer, which brought her 50,000 letters of support.

In 1974, she was made U.S. Ambassador to Ghana, and later to Czechoslovakia, and in 1976 became America’s first female Chief of Protocol at the White House.

A decade later, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences presented her with a full-sized Oscar to replace the miniature one she had been given 50 years earlier. She dedicated it to her late mother, whom some felt had exploited her.

She was devastated when, on August 4, 2005, her husband died from myelodysplastic syndrome, a bone marrow disease, at 86, after almost 55 years of marriage. Touchingly, she insisted on keeping Charles’s voice on their answering machine. ‘I don’t ever want to erase it,’ she said simply.

In 2006, Shirley Temple Black received the Screen Actors Guild’s Lifetime Achievement Award for having ‘lived the most remarkable life, as the brilliant performer the world came to know when she was just a child to the dedicated public servant who has served her country at home and abroad for 30 years’. Her own assessment of her life was more modest. ‘I class myself with Rin Tin Tin,’ she said, referring to the male German Shepherd dog that became a screen sensation. ‘At the end of the Depression, people were perhaps looking for something to cheer themselves up. They fell in love with a dog and a little girl. It won’t happen again.’

It never has. And in these less innocent days, it seems certain that never again will the world know a child star with the magic of Shirley Temple.

© Daily Mail, London