On the heels of the wild beauties of Delft

They are the living “landmarks” of rugged Delft, inextricably linked with this island located in the Palk Straits across from the Jaffna peninsula.

With an arrogant toss of their heads, manes and tails flying, they gallop along the coastline, daring anyone to come up-close. They are the wild horses which are such an integral part of Delft that one adorns the island’s symbol, along with a cow and a fish.

The Sunday Times team which spent a day on Delft, covered in white-powdery dust from head to toe, did try to capture close-up photographs of these wild horses, an extremely difficult feat.

If enamoured we were with the wild horses of Delft, intrigued were we by the ‘wild horse-catcher’, we saw riding bareback across the grassy plains.

Horse and rider seemed one, as 22-year-old M. Iridiyaraj with his face to the sun, his hair whipped back by the strong winds rushing across this island, galloped towards us, sans saddle with only his legs curling around the torso of his beloved ‘Suren’.

An image that seems to have been transported straight from the Wild West movies of yore, but the rider is sans a gun, only brandishing a lasso, as he demonstrates to us how they go about their business of catching these elusive creatures.

Iridiyaraj seems to be horse-catcher and horse-whisperer blending into one, as he murmurs endearments to ‘Suren’ and explains that it should not be taken for too long along the tarred road which acts as the main street of Delft as it is harmful to its hooves.

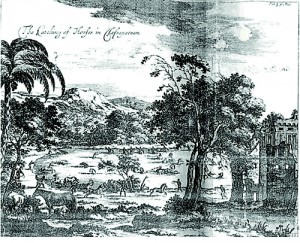

Drawing of the capture of horses in Jaffna observed by Baldeus (in 1672). This appears to be a scene in Delft. (Reproduced from the IUCN report)

Reticent about how many wild horse-catchers there are as they feel that it is a practice that is frowned upon, the unfortunate inability on our part to communicate in the language of currency, which is Tamil, adds to our problems. It is at the persuasion of Fr. J. David of the American Ceylon Mission’s Delft Church that Iridiyaraj agrees to talk to us.

Yes, there are several families which have captured a few wild horses and domesticated them, he smiles, adding that their methods of capture include two or three of them stealthily sidling up to a herd on their domesticated horses, surrounding a few of the wild ones and lassoing a wild one rodeo-style. When they take to their heels on sensing danger and thunder across the plains, “elavala allanawa”, he says in broken Sinhala.

Another ruse is to entice a wild one by using a domesticated one, smiles Iridiyaraj who like the other youth on the island come from impoverished homes, with jobs very hard to come by. He attempts to add a few rupees to the family kitty by doing a little masonry work whenever it is available or going out to sea for fishing like numerous others.

‘Suren’ he secured about four years ago and it is obvious that the bond between youth and horse is very strong. The domesticated horses are used for riding or carrying goods around the island where transport is difficult with the common ‘mode’ being bicycles or bullock-carts.

It is the culture of Delft to go on horse-back, adds Iridiyaraj, a view that is confirmed by an exhaustive study carried out by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) just last year which estimates that the wild horse population is around 1,000.

Pointing out that the feral Delft ponies are a ‘unique’ species, this IUCN study titled ‘Sustainable Development of Delft Island: An

Fr. J. David

ecological, socio-economic and archaeological assessment’ states that among the 11 mammal species recorded on the island are the Equus caballus (Delft pony or wild horse) in the grassland habitats.

The presence of these wild horses bears evidence of a thriving industry during the colonial period, states the study, adding that Delft had been used as a breeding centre, from which horses were distributed to several South Asian countries. Some of the ruins left by the Dutch confirm that there were stables for a large number of horses, as well as areas where they were treated.

The study picks on the descriptions by two Philips — Philip Baldeus (a Dutch minister) in 1672 and much later in our times by American Ambassador Philip K. Crowe in 1954 about these beautiful creatures.

“These ponies were introduced to the island originally by the Portuguese, who at the same time trained local inhabitants on how to use a lasso. In 1672, Philip Baldeus visited Delft island, and observed that ‘these horses that were brought into the Delft, which multiplying in time, produced a certain kind of horses that are very small but hardy and fit to travel on stony and rocky ground…..they live in the wilderness and are taken by catching them in snares or ropes’,” it states.

“The stallions appeared to be better types than the mares, and no new blood has been introduced since the British period by Lt. Nolan in 1824,” it quotes American Ambassador Crowe as stating.

The IUCN study carried out by S. de A. Goonatilake, S. Ekanayake, T.P. Kumara, D. Liyanapathirana, D.K. Weerakoon and A Wadugodapitiya further states that “historically, the Portuguese, Dutch and British used the island (Delft) as a breeding ground for horses and cattle, and ploughed the land to create grazing areas for these species”.

Warning that the pony population is threatened due to overgrasing of pasture lands by the large population of cattle, it states that during the height of the dry season, a high incidence of cattle and pony mortality has been reported due to the lack of adequate food and water.

The issue of water not only affects the wild horses but also the men, women and children of Delft, a fact that the Sunday Times hears over and over again from the people as well as Navy personnel.

Delft’s Divisional Secretary Alavipillai Siri believes that in the 2011 dry season about 5% of the wild horse and cattle populations succumbed for lack of water.

The Navy built several troughs in the areas where the wild horses roam to keep them from dying of thirst, he said.

The IUCN study also sends out a word of caution about the branding of calves. Some people capture and mark the calves of the ponies using improper branding methods, which can result in infections. “This is a major cause of death among calves.”

Flipping back the pages of time and going on the records of Baldeus, the study points out that reliable evidence about Delft can be found in the Portuguese notes, ‘llba das Vacas’ which means ‘cow island’, with the Portuguese reportedly ploughing the land and preparing an artificial pastureland for horses and cattle.

According to Ambassador Crowe Irish Lieutenant Nolan, who served in the 4th Ceylon Regiment during the early part of the nineteenth century, had in 1811 been given the task of growing flax (Linum usitatissimum) with the aim of supplying the government with canvas. The next year (1812), he had been assigned the additional task of breeding the horses introduced to the island by Portuguese and Dutch settlers.

He had introduced several new breed stocks to the island. As the British Empire expanded, the demand for horses by the cavalry increased and records indicate that horses were shipped to the small island, Iranaitivu, from Delft for pasturage, as sufficient fodder could not be found on the island to support the ever increasing horse population, Crowe has said.

Pointing out that except for a few families which have captive horses while the others roam free, the IUCN urges that the viewing of these wild horses could be developed into an attractive product for tourists.