Sunday Times 2

India’s disrupted democracy

NEW DELHI – India’s 15th Lok Sabha (the lower house of Parliament) passed into history ignominiously this month, following the least productive five years of any Indian parliament in six decades of functioning democracy. With entire sessions lost to opposition disruptions, and with frequent adjournments depriving legislators of time for deliberation, the MPs elected in May 2009 passed fewer bills and spent fewer hours in debate than any of their predecessors.

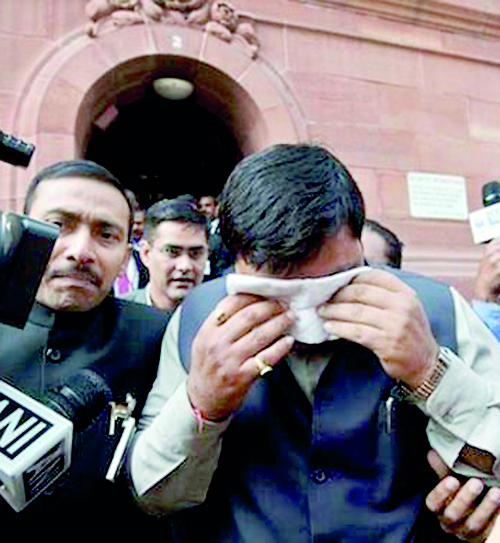

Betrayal of people’s trust: Pepper-sprayed Indian MPs coming out of Lok Sabha

As if that were not bad enough, the final session witnessed new lows in unruly behaviour, with microphones broken, scuffles in the Well of the House, and a legislator releasing pepper spray to prevent discussion of a bill he opposed. In the latter incident, the Speaker was rushed, choking, from her seat, and three asthmatic MPs were taken to the hospital, prompting the offender to explain that he was acting in self-defence against those who sought to prevent him from engaging in less exotic forms of disruption.

To those of us who sought election to Parliament to participate in thoughtful debate on how to move India forward, and to deliberate on the laws by which we would be governed, the experience has been deeply disillusioning.

To be sure, democracy has proved to be an extraordinary instrument for transforming an ancient country — one featuring astonishing ethnic, religious, linguistic, and cultural diversity, myriad social divisions, and deeply entrenched poverty — into a twenty-first-century success story. Only democracy could have engineered such remarkable change with the consent of the governed, and enabled all to feel that they have the same stake in the country’s progress, equal rights under its laws, and equal opportunities for advancement. And only democracy could defuse conflict by giving dissent a legitimate means of expression. Some observers express astonishment that India has flourished as a democracy; in fact, it could hardly have survived as anything else.

But the “temple of democracy,” as Indians have long hailed their parliament, has been soiled by its own priests, and is now in desperate need of reform. Parliament’s functioning has become, to most Indians, an embarrassment and, to many, an abomination. People turn on their televisions and watch in disbelief as their elected representatives shout slogans, wave placards, scream abuse, and provoke adjournments — indeed, do almost anything but what they were elected to do.

The result is that most Indians consider Parliament a colossal waste of time and money. After all, its dysfunction not only cheapens political discourse; it also delays essential legislative business. Bills languish, policies fail to acquire the legal framework needed for implementation, and governance slows.

The errant MPs are not just betraying their voters’ confidence; they are also betraying their duty to the country and discrediting democracy. But the complacency with which the political establishment accepts the disruption of Parliament suggests that even experienced politicians do not understand this.

Because a parliamentary system usually results in predictable outcomes, with the ruling majority typically getting its way, India’s opposition MPs (and any government MPs who disagree with the cabinet’s position on a specific issue) prefer disruption to debate. And this is greeted on both sides of the aisle with a shrug, as if intentionally drowning out one’s colleagues with shouted slogans were just another parliamentary maneuver, as valid as a filibuster or an adjournment motion.

In fact, an unwritten but sacrosanct convention ensures that the Speaker almost never uses the position’s authority to suspend or expel errant members, except when there is a consensus between the government and the opposition to do so — which of course rarely occurs. (The pepper-spraying MP was, however, suspended for the rest of the session. Even complacency has its limits.)

What the political establishment overlooks is the broader damage that such behaviour does to Parliament’s public standing, and therefore to democracy itself. The shambolic performance of elected parliaments in Europe, especially in interwar Germany and Italy, had a great deal to do with the rise of authoritarianism and fascism in the first half of the twentieth century. When democracy is discredited by its own practitioners, there is much greater public willingness to embrace a seemingly efficient alternative.

India’s neighbours have proved this often enough, welcoming the overthrow of elected governments in popular coups. India has never seemed likely to succumb to a similar tendency, but the irresponsible custodians of Indian democracy should not tempt fate.

If India’s founding fathers, like the passionate democrat Jawaharlal Nehru, had not been cremated, they would be turning over in their graves. With a general election to be held by the end of May, voters should insist that those who seek to represent them in Parliament go there to debate and deliberate, not to disrupt and destroy. As of now, that seems to be a forlorn hope.

Shashi Tharoor is India’s Minister of State for Human Resource Development. His most recent book is Pax Indica: India and the World of the 21st Century.

Copyright: Project Syndicate, 2014. Exclusive to the Sunday Times

www.project-syndicate.org