Sunday Times 2

Remembering Colvin and his prophetic words on the executive presidency

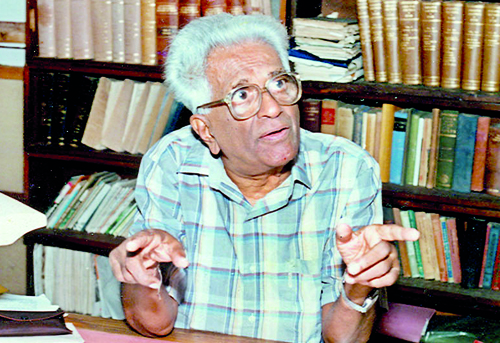

This week we remember Dr. Colvin R. de Silva, on the 25th anniversary of his death on February 27, 1989. The country lost a brilliant lawyer, a fine orator and an exemplary parliamentarian. Hardly a week passes without a newspaper article lamenting the absence of leaders of his ilk.

It was the Left that spearheaded the campaign against the introduction of the executive presidency in 1978 and today we remember Colvin when the country is feeling the full force of the executive presidency, strengthened to the utmost by the Eighteenth  Amendment.

Amendment.

If there had been one statement that epitomised the Sri Lankan Left’s unswerving opposition to the executive presidency and its preference for the parliamentary form of government, that was one made by Dr. de Silva in the Constituent Assembly in1971: “There is undoubtedly one virtue in this system of Parliament … and that is that the chief executive of the day is answerable directly to the representatives of the people continuously by reason of the fact that the Prime Minister can remain Prime Minister only so long as he can command the confidence of that assembly. …We do not want either Presidents or Prime Ministers who can ride roughshod over the people and, therefore, first of all, over the people’s representatives. There is no virtue in having a strong man against the people.” He was responding to a proposal by J.R. Jayewardene that the country should have an executive presidency. He explained: “We want an evolving society, and therefore we want a constitutional system that permits the evolution, that facilitates the evolution, that propels the evolution, and that itself evolves with the evolution. Nothing less would do.”

When Jayewardene introduced the executive presidency in 1978, Dr. de Silva, who warned in 1955 of the dangers of making Sinhala the only official language (‘one language, two nations; two languages, one nation’) was again at his prophetic best: “We confess to a new worry amidst it all. ‘I am the leader of 14 million people.’ Ominous words which stir still frightening memories. Was it not Hitler who said: ‘I am the leader of the German people, of all Germans wherever they are!’? And all the world knows where he led them and into what hell he plunged the world. The slogan of the UNP today is ‘One party, One policy, one Leader – and Leader is always with a capital ‘L.’ Are we heading for one party, one policy, one Leader, for the nation too? It is a grim Presidential beginning…. The hour may have been auspicious for the President. But was it auspicious for the nation?” (Sri Lanka’s New Capitalism and the Erosion of Democracy, p. 34)

By the Third Amendment, President Jayewardene strengthened the presidency further by permitting a President in his first term of office to seek another term at any time after completing four years. The President can thus choose the date of election most advantageous to him. The Constitution now permits the President to call both Parliamentary and Presidential elections early.

Some restrictions were imposed on the executive presidency by the Seventeenth Amendment. Appointments to certain high posts including the higher judiciary and the independent commissions were through a Constitutional Council.

The Eighteenth Amendment was introduced by President Mahinda Rajapaksa, ironically the leader of a party (SLFP) which had been opposed to the executive presidency throughout. The Amendment removed the two-term limit and replaced the Constitutional Council with a Parliamentary Council. The President is only required to seek the ‘observations’ of the Parliamentary Council. The Eighteenth Amendment also took away some powers of the Elections Commission.

The role of the Left

The performance of the Left in relation to the Eighteenth Amendment was disappointing, to say the least. The three Left parties campaigned against the Amendment. The LSSP decided, not once but twice, that its two MPs should not participate in the vote. Finally however, all five Left MPs voted for the Amendment. The excuse given was that the Amendment would have received a two-thirds majority even without the Left members! The conduct of the Left members whose parties and departed leaders had been in the forefront of the opposition to the executive presidency was a classic instance of ‘kiri kalayata goma tikkak demma wage’ (‘putting a blob of cow-dung into a pot of milk’) as the Sinhala saying goes. The CP has since then admitted that voting for the Amendment was a mistake.

Reform or abolition?

An argument against the abolition of the executive presidency is that the presidency leads to stability. Proponents of the presidency say that in view of the political and economic challenges faced by a developing country such as Sri Lanka, a strong government freed from the whims and fancies of the legislators and which can take tough, unpopular decisions that are in the long-term interest of the country is needed.

Dealing with the ‘stability’ argument which Jayewardene put forward, and which is echoed today by apologists for the executive presidency in the present-day SLFP, Dr. de Silva stated in the Constituent Assembly: “I am very anxious to make this clear; this is an effort. This word ‘stability’ covers a multitude of wrong propositions. Stability! What kind of stability are we talking of? A stability that comes from the withdrawal of the central power from the influence of the masses? In other words, the people shall be kept outside, with only one function: as Marx said so long ago, ‘They choose once in five years who shall oppress them for the next five years’! That is not my concept of democracy, parliamentary or otherwise.”

It is also argued that the Sri Lankan state would not have defeated the separatist threat but for the executive presidency. In a parliamentary form of government too, the government has complete control over the armed forces. Executive power is exercised in the name of the President who must act on the advice of the Prime Minister. The executive presidency brings in no ‘magic’. What a Prime Minister cannot do to the extent that an executive president can is to manipulate the political process — ‘political jilmart’.

Dr. Colvin R. de Silva’s description of the system of government under the 1978 Constitution as a constitutional presidential dictatorship dressed in the raiment of a parliamentary democracy has proved to be true. With no term limit and the Seventeenth Amendment out of the way, the executive presidency in Sri Lanka has certainly become one of the strongest and vilest, if not the strongest and vilest, presidential systems in the ‘democratic’ world.

What the future bodes

What of the future of the executive presidency? The UNP which defended the executive presidency until it felt the full force of its own proud product has at last made up its mind on its abolition. Tamil and Muslim parties no more have illusions that it gives their communities any protection. Ironically, it is only the present SLFP leadership and hardliners supporting it that are today unequivocally for its retention.

While President Jayewardene was able to impose his will on the UNP in the post-Senanayake period, President Rajapaksa has not been able to do the same with the SLFP, being a party that suffered immensely under the executive presidency of both Presidents Jayewardene and Premadasa. Speaking at the 76th anniversary of the LSSP, Chamal Rajapaksa, the President’s elder brother and Speaker of Parliament, commended the LSSP for its stand on the executive presidency and added that a single person should not be given all powers and that the executive presidency should be abolished, adding the caveat ‘in the future, after making use of it’ obviously not wanting to offend his sibling.

While President Rajapaksa is in no mood to abolish the executive presidency, doing so under pressure cannot be ruled out altogether. Already, there is talk of a ‘single-issue’ common candidate, the single issue that could unite the entire opposition and catalyse dissent within the SLFP to turn into revolt being the abolition of the executive presidency. If there is a serious challenge to his position, Rajapaksa may well take the wind off the sails of the opposition by abolishing the executive presidency. However if he maintains his current stand, there is every likelihood that abolition would become a rallying point for the opposition and dissidents within the SLFP.

The Left parties recently called for abolition without holding another Presidential election and this has been welcomed, including by members of the SLFP. However, there are some in the Left who argue that if President Rajapaksa does not abolish the executive presidency and the call for abolition is taken up by a broad electoral coalition that puts forward a common candidate, the country would move to the right! One may only ask: Is there any more room on the right?

It is best that we let Dr. de Silva reply to these ‘leftists’. He explained in 1971 that what the Right wanted was not parliamentary democracy but autocracy, to the extent that the people can be made to tolerate it. “It is not an accident that the views of the United National Party have undergone this evolution. It reflects the evolution of the increasing peril to the capitalist class in the social system of Ceylon. Therefore they want a constitution … where they are sure of one thing: get away from the common man, and thus the repository of wisdom known as the capitalist class can rule in stability!” Now that the present leadership of the SLFP (as opposed to its wider membership) has come around to the views, and politics, of J.R. Jayewardene, what Dr. de Silva said applies to it as well.

(The writer is a President’s Counsel)