‘Storming’ Bogambara

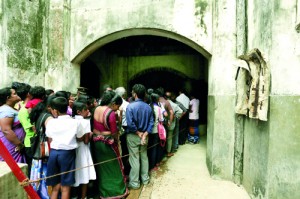

A morbid curiosity or is it fascination impels us with the hundreds of men, women, some carrying tiny babies, and children including those in school uniform, to the “star” attraction.

The stampede, bypassing everything else, is towards the red-painted gallows.

A clamour is obvious when the Sunday Times team climbs up to the gallows on Tuesday afternoon amidst a massive pushing-and-shoving crowd.

“Ellung-gaha apahu genne.”

The outcry over and over again that capital punishment be implemented is being thrown across the gallows to none other than Rehabilitation and Prison Reforms Minister Chandrasiri Gajadeera.

Not only for murder, should criminals be sent to the ellung-gaha but also for sthree saha lama dushanaya (crimes against women and children), they plead, taking time on their way in or out of Bogambara to laboriously write in the CR books provided for their views.

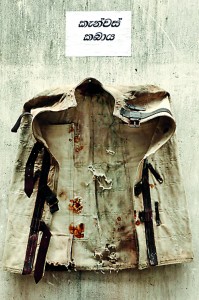

The jacket of the condemned

As people surge through the Bogambara prison (it has been opened to the public from March 15 to 25), reading the pathetic messages left by its inmates on death-row and clicking photos “behind bars” or wandering into the 400-odd cells where more than 2,000 had been detained, human rights activists are of the strong opinion that capital punishment is not the answer to the crime wave sweeping across the country.

Prevention and rehabilitation are the need of the hour, they stress, as prison officials said that over 500 have been hanged at Bogambara with an inquisitive public questioning them closely.

The historic Bogambara Prison is to be handed over to President Mahinda Rajapaksa with speculation that it is to be turned into a museum or a boutique hotel.

With its massive hooks and the plank that is levered down to create the jerk which would see the culmination of a “judicial” hanging, Bogambara prison officials state that these are the only gallows in the country where three can be executed simultaneously.

It is at this very same gallows that H.G. Dharmadasa, as the young and smart Superintendent (SP) of the Bogambara Prison, says he had the “misfortune” of “officiating” at the last few executions of this country, back in the 1970s.

Now 70, it is reminiscence time for him when the Sunday Times contacted him. Before we are “led” through the tales of the gallows, he talks about the “well-known” remand prisoners he had under him during his tenure as SP from 1974-79.

The gallows where three could be hanged together

Dimu Jayaratne, the current Prime Minister, was one, walking on crutches as he had a broken leg being attended to at the Prison Hospital and also Mavai Senathirajah (now of the Tamil National Alliance) who had been transferred to Bogambara after a Black Flag protest at the Magazine Prison in Colombo. There was also a Tamil poet called Kasi Ananthan in the Black Flag protest group sent to Bogambara to defuse a riot situation at the Magazine Prison.

Of the seven executions that he was officially part of, three he remembers vividly.

They were the last three in 1975 – two sentenced to death in the Thismada murder case and the final being the infamous Maru Sira. Thereafter, Sri Lanka suspended the death penalty.

H.G. Dharmadasa officiated at the last hanging

While he remembers D. Richard and T.M. Jayawardena being hanged a day after each other, Mr. Dharmadasa says tough Richard a man of few words, went to his death without a tremble or outward sign of remorse for killing a young woman teacher.

The scenario was different with Jayawardena who howled and wailed all the way to the gallows that he was innocent on the grounds that he only held the teacher’s legs tightly together so she wouldn’t struggle while Richard cut her neck.

It is, however, not only Maru Sira’s execution but also the drama in its wake that is seared into Mr. Dharmadasa’s memory.

Mr. Dharmadasa who is practising as a lawyer in his retirement after being the first Commissioner-General of Prisons in the mid-1990s (with the topmost post in this sector changing from Commissioner) is currently on a committee headed by a retired Court of Appeal Judge to make recommendations on the commutation of the death penalty to life imprisonment for those facing capital punishment.

The death penalty is passed on those found guilty of murder or having in their possession over two grams of heroin.

Through the corridors of time: The ward where Saradiel was locked up during British rule. Pix by M.A. Pushpa Kumara

Mr. Dharmadasa is adamant that contrary to popular belief that it was the Thismada murderers, the last to be hanged was Maru Sira. It was in 1975 that D.J. Siripala alias Maru Sira from Anuradhapura who had been tried in absentia and sentenced to death for the murder of a man had been captured and sent to Bogambara to have his tryst with the hangman.

Maru Sira was a mild, soft-spoken, fair, thin man, recalls Mr. Dharmadasa. With the date of the execution being decided by the President’s Office (formerly that of the Governor-General), a special guard had been placed the previous night by Maru Sira’s cell.

When Mr. Dharmadasa, as was his custom with anyone awaiting execution, visited him around midnight, Maru Sira who had been awaiting a reprieve was visibly upset. The big people don’t know when they would have to die, but at least the humble know, he had told Mr. Dharmadasa. At the conclusion of his visit, the young SP had made a “gate entry” that the prisoner “is in good condition and the security is in  order”.

order”.

A day of execution was usually a nervous one for Mr. Dharmadasa and with only a quick cup of tea but no breakfast, as he just didn’t have the stomach for it, he had been at his office by 7 in the morning.

The execution was set for 8 a.m. with the two hangmen or alugosuwo being sent from Welikada the previous day having reported in the night and kept within Bogambara to prevent any abduction, to foil the next day’s activity. They had also carried out a test-run, having taken the height and weight of the condemned prisoner, filling up a bag of sand to that weight and dropping the noose line to ensure that the rope or bar would not break.

“These were well-thought of and time-tested systems,” says Mr. Dharmadasa

But things went awry the moment two jailors rushed into Mr. Dharmadasa’s office claiming that Maru Swira was not waking up to be prepared for the gallows. With Maru Sira having a history of violence, Mr. Dharmadasa had ordered them to handcuff and also place ankle restraints on the prisoner. All efforts to rouse Maru Sira, though, had been of no avail. When summoned, the Prison Medical Officer who was living at Chulapaya, the doctors’ quarters in Kandy had examined him thoroughly and come to the conclusion that “he was feigning illness”.

As the time nudged up to 8 o’clock, Mr. Dharmadasa was in a quandary. To change the decision, he would have to contact the President’s Office and get a postponement. “It was a tough call,” he says.

It was then that Mr. Dharmadasa decided to go ahead with the execution. The protocols had been followed with the two jailors who admitted the prisoner to Bogambara after the death sentence had been passed on him and had meticulously marked height, weight, distinguishing marks such as tattoos or scars identifying that it was the very same man. The final signal to pull the lever had come from Mr. Dharmadasa.

By his side were ASP Philips, Chief Jailor Tennekoon, two Jailors, the two hangmen, two or three prison officials, the doctor and a Buddhist monk who had come to chant pirith, he says going back to the ’70s.

The usual procedure was that the prisoner was brought to the cell closest to the gallows on the morning of the hanging from his high-security cell. He would then be dressed in a jumpsuit of coarse off-white material, with a broad body-belt tied around his waist. His hands would also strapped to it. Onto his head, covering his face and neck, was lowered a bag-like head gear made of the same coarse material, after which he would be brought to the scaffold, says Mr. Dharmadasa, adding that all other prisoners were locked up in their cells during an execution to prevent trouble.

As Maru Sira’s body seemed limp, the guards brought him on a stretcher and held him up for the noose to be put around his neck. The moment the executioner pulled the lever, the scaffold opened and the man dropped down. The doctor then carried out a post-mortem examination and recorded the “death caused by the rupture of the spinal cord due to judicial hanging”.

As Maru Sira’s wife had declined to accept the body, he had been buried at Mahaiyawa government cost.

Two days later, says Mr. Dharmadasa, he was nominated for a scholarship to do his postgraduate studies at the London School of Economics and went to the United Kingdom not knowing that a storm was brewing back home in Sri Lanka.

With Maru Sira’s wife hearing murmurs and whispers when she came on the day of the execution that he had been “marala elluve” (killed and hanged), the media had gone to town with the story. Heavily immersed in his studies, Mr. Dharmadasa had got wind of the Maru Sira drama unfolding back in Sri Lanka through the newspapers at the High Commission in London.

Reading that a Special Presidential Commission of Inquiry was being appointed to look into the matter, he had written to the then Commissioner of Prisons, J.P. Delgoda that he would come back to give evidence on condition that he be permitted to return to his studies.

Maru Sira’s body had been exhumed, with the postmortem revealing traces of a lot of tablets of a psychiatric medication that is usually prescribed to prisoners on death row to calm their nerves. He had been collecting this medication from his prisoner-friends and hiding it in a hole in the wall he covered with a paan paste. “He must have taken it after my visit to him at midnight,” says Mr. Dharmadasa who had not been summoned give evidence before the Presidential Commission.

Another finding through the postmortem was that the spinal cord had not ruptured as Maru Sira had not been standing but had been held up for the noose to be put round his neck and the noose was not tight.

With the Presidential Commission giving a vague report that “prison authorities were responsible” for administering the psychiatric drug, it had been sent to the Attorney General who in turn sent it to the Kandy Police to fix responsibility. The Kandy Police had found that no investigation could be carried out as responsibility had not been fixed on an individual and the matter ended there.

The only people who made money out of this drama were those who produced the popular films ‘Siripala and Ranmenika’ and ‘Maruwa Samaga Wase’,” adds Mr. Dharmadasa.

| It all began in 1876…

‘Maha Ulu Gedera’ was how Bogambara was affectionately called, the name being coined due to its roof being made entirely of Sinhala or local ulu (tiles). Well and truly dispelling the misconceptions that have been doing the rounds, Mr. Dharmadasa is quick to point out that Bogambara, the second largest prison in the country next to Welikada, was built by the British way back in 1876. Ehelepola Walauwwa was not turned into the Bogambara Prison, he reiterates, pointing out that, that is located opposite the President’s House on Raja Veediya and became the Kandy Remand Prison. Prison officials are of the view that Bogambara on 5.05 hectares had been built by the British after filling a part of the wewa and the body of Ehelepola Kumarihamy had been taken out of the water after her drowning at a spot on this land. The Bogambara building had cost an estimated Rs. 365,365.65. A well-known inmate of the past had been Saradiel who had been executed here. Now the prison land has been bifurcated by Aluthgama Dhammananda Himi Mawatha, they add. Debunking other tales of well-known political prisoners of yore Colvin R. de Silva, N.M. Perera, Phillip Gunewardene and Edmund Samarakkody being incarcerated by the British at Bogambara, Mr. Dharmadasa says they were kept in the Kandy New Detention Prison, the buildings of which are now occupied by the Kandy Sinha Regiment. He gives a glimpse into the prison system — first offenders would be sent to Welikada in Colombo; those who had more than two convictions and fewer than four would be sent to Bogambara; and those with over four convictions – re-reconvicted criminals – would find a home at Mahara. Bogambara was also the only other prison next to Welikada where hangings took place and the catchment areas from which criminals were sent were the north, the east, the north-central and the central regions, with Welikada covering the other areas. Marvelling at Bogambara’s construction, Mr. Dharmadasa says the three-storey building has no concrete, only brick, lime and wood. The wooden floors are all of teak, and no concrete is involved. The walls, of course, are huge, tapering up. It may have been in a corner of Kandy town when it was built but now it is in the heart of the city, he says, pointing out that on one side is the playground and on the other the market. A sombre note is added by prison officials who state that the branches of the bo-tree spreading in the direction of the gallows wither and die as if in sorrow. |