Sunday Times 2

Red light for Buddhist monks in driving seat

View(s):The Court of Appeal in a landmark judgment has ruled that the issuance of driving licences to Buddhist priests not only violates the Vinaya Rules but also the Constitution.

The ruling came after a two-judge bench of the Court of Appeal heard a petition filed by three Buddhist monks whose applications to obtain driving licences were turned down by the Motor Traffic Commissioner after he consulted the Buddhist Affairs Commissioner.

“The issuance of a driving licence to Buddhist Monks would offend the Buddhist way of life and the Buddhist culture in our country. The Constitution of Sri Lanka itself, by its Chapter II and Article 9 protects the Buddhasasana, and the Judiciary being one arm of the State, is bound to give effect to the above Constitutional Provision,” Justice Anil Gooneratne said in his ruling — with Justice Deepali Wijesundera agreeing.

The petitioners in this case Ven. Dr. Paragoda Wimalawansa Thera, Ven. Bodagama Seelavimala Thera and Ven. Diyagama Somarathna Thera cited the Motor Traffic Commissioner, Deputy Commissioners and the Buddhist Affairs Commissioner among others as respondents.

Attorney-at-Law Saliya Peiris with Anjana Ratnasiiri appeared for the three monks while Deputy Solicitors General Janak de Silva and Milinda Gunatilleke along with President’s Counsel Uditha Egalahewa with Ranga Dayananda appeared for the respondents.

We produce here the excerpts of the judgment. For the full text of the judgment, visit www.sundaytimes.lk.

These are three Writ applications and the Petitioners in these applications are Buddhist Priests. The subject matter of these Writ Applications pertains to issue of driving licences in their names and capacity of Bhikkus. Petitioner Bhikkus in the three applications seek a Writ of Certiorari (in 1978/04) to quash letter of 27.7.2004 (P11) a decision not to accept and process the application for a driving licence, consequently not to issue a licence, and a Writ of Mandamus to issue a driving licence according to law compelling the Respondents to issue the licence. Only a Writ of Mandamus is sought in Application Nos. 1459/06 & 1458/06 to compel the Respondents to process the application and issue a licence according to law. Hearing of these applications were consolidated and taken up together and all the respective learned counsel both from the unofficial and official bar addressed and assisted this court to enable court to arrive at a decision.

A Buddhist monk gets into a car (file pic): The petitioners claimed if they are allowed to drive, they will be able to carry out their duties more efficiently

I would for purpose of clarity very briefly and as far as I could, relate the facts to enable any reader of this judgment to understand the background facts. In Case No. 1978/04, to begin with letter P5, it is stated therein by the Commissioner of Motor Traffic that there is no legal impediment according to the Statute i.e Motor Traffic Act for a Buddhist Priest to obtain a driving licence. However letter P5 addressed to Secretary of the Buddha Sasana Ministry, his views are sought by the Commissioner as to whether it is objectionable to issue a licence since the Petitioner is a Bhikku. A petitioner desirous of obtaining a driving licence had addressed several letters to persons in authority explaining the position that there is no impediment for a Bhikku to obtain a driving licence. Commissioner of Motor Traffic was informed by letter of 13.7.2004 by the Commissioner of Buddhist Affairs that the question of issuing a licence to a Bhikku was conveyed to the Samastha Lanka Sasanarakshaka Mandalaya and at its meeting held on 6.7.2004 the above Mandalaya had informed the Commissioner of Buddhist Affairs that it would not be appropriate to issue driving licences to Bhikkus. Thereafter the Commissioner of Motor Traffic by letter P11 dated 27.7.2004, informed the Petitioner accordingly of the above decision. The Petitioner on receipt of P11, filed the application bearing No. 1978/2004 for Writ of Certiorari/ Mandamus.

In C.A Application Nos. 1459/06 & 1458/06 a Writ of Mandamus is sought to compel the 1st & 3rd Respondents to issue a licence. The Petitions filed by the respective Petitioners refer to several statutory provisions to demonstrate that the Petitioners are entitled to be issued with a driving licence having satisfied all required statutory provisions of the Motor Traffic Act. I find that very many factual positions of the Petitioner as averred in the petition are not disputed by the Respondents. However it would be relevant to note the position of the Respondents in these two applications, gathered from the objections filed of record as follows. It is inter alia pleaded that:

(a) It is not a common occurrence for a Buddhist Priest to apply for a driving licnence;

(b) As such, the officer at the counter did not accept the Petitioner’s application but sent it to the Deputy Commissioner of Motor Traffic;

(c) On a very few previous occasions where applications had been made by Buddhist Priests for driving licences the Commissioner of Buddhist Affairs was consulted on the question of the issue of a driving licence;

(d) After making relevant inquires and consultation he had informed on a number of previous occasions that it was not proper to issue driving licences to Buddhist Priests;

(e) Consequent upon such consultation with the Commissioner of Buddhist Affairs, the then Commissioner of Motor Traffic had duly issued circular bearing No. S/D.L/MIs dated 4.4.1988, (R3) which laid down the policy of not issuing driving licences to Buddhist Priests.

(f) Ven Diyagama Wimalasara of the Ganewatte Purana Viharaya of Hokandara and by his letter dated 17.2.1995 had requested that a driving licence be issued to him;

(g) The said request of the Ven. Diyagama Wimalasara of the Ganewatte Purana Viharaya of Hokandara had been referred to the Commissioner of Buddhist Affairs by the letter dated 9.3.1995 and he had by his letter dated 19.6.1995 intimated to the then Commissioner of Motor Traffic that driving licences should not be issued to Buddhist Priests since it would be contrary to the concepts and traditions of the Buddhist priesthood.

(h) The Mahanayakes of the Malwattu, Asgiri, Amarapura and Ramanna Nikayas by letter dated 1.11.2006 wrote to the Commissioner of Buddhist Affairs and sought his intervention to protect the Buddha Sasanaya from wrongful acts such as priests seeking driving licences;

(i) By letter dated 16.11.2006 several eminent Buddhist Monks also wrote to the Commissioner of Buddhist Affairs setting out the reasons why it is against Buddhist principles to issue driving licenses to Buddhist Priests.

(j) Views of the Commissioner of Buddhist Affairs was also taken into consideration.

The Respondents have referred to Constitutional provisions which are embodied in the Constitution to protect the Buddha Sasana. Hearing of these applications went on for several days, and at the end of it parties were permitted to file Written Submission. I have also to mention that at a certain early stage of the hearing of application No. 1978/2004, a preliminary objection was raised by the Respondents on the failure of the Petitioner to make the necessary party namely the Commissioner of Buddhist Affairs, a party before court. Having heard the parties the Court of Appeal by its order dated 20.7.2007 rejected the preliminary objection and decided to proceed with the application on its merits. The Commissioner of Motor Traffic moved the Supreme Court against the above order of 20.7.2007, and sought Special Leave to Appeal, and the Supreme Court granted leave on 6 questions of law. The Supreme Court

|

|

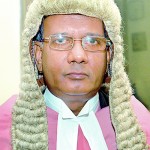

| Justice Anil Gooneratne (left) and Justice Deepali Wijesundera

say the life of a monk in its pure form is incompatible with lay life |

|

however after hearing, dismissed the appeal and affirmed the order of the Court of Appeal dated 20.7.2007.

The learned counsel for the Petitioner Mr. Saliya Peiris demonstrated to court that official Respondents cannot abdicate their powers vested in them in terms of the statutory provisions. The suitability of the individual on the issue of a driving licence is not a matter to be debated, when there is due compliance with the provisions of the statute.

Learned Counsel for the Petitioner also urged that no specific ‘Vinaya’ rules which guide Buddhist Monks are violated and that the ‘Vinaya’ does not prohibit the issue of a licence. He also submitted that the decision taken by the Commissioner-General of Motor Traffic in consultation with the Commissioner of Buddhist Affairs regarding the issue of a driving licence is arbitrary and illegal. There is no legal or a moral bar for a Monk to obtain a driving licence. The refusal to issue the licence does not refer to Article 9 of the Constitution.

The learned Deputy Solicitor General Janaka de Silva who appeared for the Commissioner of Motor Traffic in application 1978/04 stressed four points and emphasised the fact that in view of the provisions contained in Article 9 (chapter II) of the Constitution the Republic of Sri Lanka, gives Buddhism the foremost place and a duty is placed in the state to protect and foster the Buddha Sasana. As such the overriding power vested in the Constitution would negate any statutory provisions enacted by the legislature. Accordingly issuance of a driving licence to a Bhikku would directly offend the above Article of the Constitution. In support of the above he relied on the case of Rev. Sumana Thera to be admitted and enrolled as an Attorney-at-Law, reported in 2005 (3) SLR at 373. The case itself though in favour of the Buddhist Monk to be admitted and enrolled as an Attorney-at-Law, the contention of counsel who appeared for the Colombo YMBA and All Ceylon Buddhist Congress in that case is that no Bikkhu could practice as a lawyer without violating religious precepts, i.e Bikkhu’s way of life is incompatible with that of a lawyer. (I have to stress on the fact that the case of Rev. Sumana Thera contained in the above case laws was in fact cited by counsel appearing on both sides. However this case discusses many aspects of a Bhikku’s way of life and the dissenting judgment of Wanasundara J. guide and support the case of the Respondent to a great extent as far as in the cases in hand).

Thereafter, the learned Deputy Solicitor General contended that the Mahanayakes of the Malwatta, Asgiri, Amarapura and Ramanna Nikaya had expressed their disapproval to the issue of a driving licence to a Buddhist Monk and sought the intervention of the Commissioner of Buddhist Affairs.

This court also had the benefit of hearing Mr. Milinda Gunatilleke D.S.G. who appeared for the Commissioner of Motor Traffic in CA 1458/2006. He supported the view of his colleague Mr. Silva.

The other address of counsel before this court was by Mr. Egalahewa President’s Counsel for the 2nd to 5th Added Respondents.

The learned President’s Counsel made reference to page 373 of the abovementioned Sumana Thera’s case where it is stated that when the Vinaya was framed profession of lawyers was totally unknown … Vinaya Pitaka contains statements regarding discipline and conduct of a Bhikku. They are made by Priests who are the final arbiters on such matters relating to the order to which Priests belong and to whose discipline a Priest is subject to and these opinions can hardly be questioned by court and must be accepted by court. He also referred to pg. 375of the above case and emphasized that the Vinaya has become and now has the force of customary law of the land and therefore enforceable by courts. Rules laid down by the Buddha for the discipline and personal conduct of his disciples is enforceable through civil courts, by laymen as customary law.

The three Writ applications filed by Buddhist Monks would be of some importance to our country which is predominantly a Buddhist nation of which majority of the Sri Lankan population consists of Buddhists. By these three applications the 3 Bhikkus have thought it fit to agitate their right to obtain a driving licence through courts since all 3 Monks were denied an issue of a driving licence more particularly by the Commissioner of Motor Traffic who is the authority to issue such licence in terms of the Motor Traffic Act. In deciding such an issue dealt by way of a prerogative Writs of Certiorari and Mandamus, this court is bound to adopt and follow the applicable legal principles that govern the issue of such prerogative writs and also has to give its mind to the discretionary nature of the remedy. A Petitioner seeking a prerogative writ “is not entitled to relief as a matter of course, as a matter of right or as a matter of routine. (1 CLW 306.) Even if the Petitioners are entitled to relief, still the courts have a discretion to deny relief on grounds which stand against the grant of relief. Grave Public/Administrative inconvenience, may also bar the granting of the remedy although that term too is incapable of precise definition. It may differ from case to case and as such courts would have to be mindful of the consequences of the issue of the Writ. It has been held that the consequences of the issue of the writs could properly be taken into account in refusing Mandamus (1932) 34 NLR 33, 37.

In the letter produced and marked P5 the Commissioner of Motor Traffic very clearly explains the position. It is stated therein that there is no legal impediment according to the Motor Traffic Act for a Buddhist Priest to be issued a driving licence. If the statutory requirements are satisfied a driving licence should not be denied. In the applications before court it cannot be said that the Petitioners do not qualify to obtain a driving licence since all three Monks have fulfilled the required statutory requirements. However court cannot stop at that and grant the relief as prayed for since the 3 Petitioners are not layman and more particularly being Buddhist Monks who should and need to earn the respect of civil society and the Petitioners, being disciples of Lord Buddha, are bound to lead a pious life. I have to be extra mindful of the consequence that would result in the present and the future and more so the impact that would be felt within civil society and the true Buddhist population of this country in case court decides to grant the remedy sought by the respective Buddhist Monks.

On behalf of the Petitioners it was submitted that the Buddhist Monk in application No. 1978/04 finds the use of public transport inconvenient and time consuming. Therefore after undergoing training at a driving school the Petitioner Monk submitted an application for a driving licence. In the other two applications 1459/06 & 1458/06 it is stated that the Petitioners were also desirous of obtaining a driving licence since they felt that they would be able to attend to their responsibilities in a more efficient manner if they are able to drive a vehicle.

The above views of the Petitioners may not be objectionable since very many people in this country may express such views considering each persons’ convenience and responsibility. But can such views be applicable and be acceptable to Buddhist Priests?

The life of a Monk, as laid down by the Buddha, is thus at complete variance with that of lay life. The spirit and flavor of the Dhamma is one of renunciation of giving up worldly affairs, and strenuous exertion for the development of virtue and mental developments. And it is in the secluded and monastic life as a monk that the Dhamma can be practiced to the full… per Wanasundera J. vide Rev. Sumana Thera’s case 2005 (3) SLR at 390.

My views become more and more fortified having perused the entire judgment of Rev. Sumana Thera’s case. Wanasundera J.’s dissenting judgment gives details of a life of a Buddhist Monk and as to the reason it need to be incompatible with lay life.

I will also take this opportunity to discuss the middle way (Madyama Prathipadawa), a concept emphasised by Lord Buddha and the Buddhist Clergy should be mindful of this at every stage of their life. It is unquestionable that Buddhism also offers a rich reservoir of conceptual materials on all aspects of the human conditions.

I would emphasise that no Buddhist in this country, if he has acquainted himself with the teachings of Lord Buddha, would not deny the fact that a Buddhist Monk is expected to observe a certain code of conduct to overcome his desires for the objects of the world and to end his suffering. To continue the three fold practice of ‘Sila’ (morality) Prajna (wisdom) and Samadhi (tranquility) on the Eightfold path and overcome all types of craving, he has to exercise great restraint of his thoughts, desires and behavior. It is so according to the tenets of early Buddhism, and Monks who declared allegiance to Lord Buddha, the Dhamma and the Sangha.

Buddhism was the religion of our country from the time of King Devanampiyatissa till foreign occupation. Portuguese when they conquered the Maritime Provinces of Ceylon, converted many citizens to Catholicism. Dutch introduced the Protestant Religion. When the British took over Ceylon there was religious tolerance and many people reverted to the religion of our ancestors. Through the medium of religious customs many tenets of Buddhism have been accepted by the courts.

In terms of Article 9 of the Constitution, the State is bestowed upon with a duty and a responsibility to safeguard and nature the Buddha Sasana. As such the Buddhasasana which is given a wider meaning including the entire establishment, it is the duty of the State to protect and foster Buddhism. It was so from the times of our Sinhala Kings.

Article 9 reads thus:

The Republic of Sri Lanka shall give to Buddhism the foremost place and accordingly it shall be the duty of the State to protect and foster the Buddha Sasana, while assuring to all religions the rights granted by Article 10 and 14(1) (e).

Even in the ‘Rev. Sumana Thera’s case Supreme Court never hesitated to rely on Mahanayake’s views. i.e discipline and conduct of Bhikkus bound to be followed and adopted by courts. R11 & R12 emphasise unequivocally and express the view that issuance of a driving licence to a Bhikku is contrary to Vinaya Rules.

The life of a Buddhist Monk in its pure form, is incompatible with lay life. A person who enters the order should be mindful of the change of status and recall this difference as often as possible. Rev. Sumana Thera’s case pg. 367.

If not prepared from such a change of life, it is better to give up robes and lead the life of a lay person and make whatever demands needed for a lay life. It is

also no excuse to take up the position that times have changed. Times may have changed for the better or worse but Teachings of Lord Buddha cannot be changed for one’s personal gain or cravings.

It is our view that the relief sought by way of Writs of Certiorari and Mandamus should not be granted to three Buddhist Monks, in these applications. The issuance of a driving licence to Buddhist Monks would offend the Buddhist way of life and the Buddhist culture in our country. The Constitution of Sri Lanka itself, by its Chapter II and Article 9 protects the Buddhasasana, and the Judiciary being one arm of the State, is bound to give effect to the above Constitutional Provision. Whilst this court profusely thanks all counsel who assisted court, we proceed to refuse all three applications and dismiss these applications without costs.

Applications refused and dismissed.