NCC carves a future for them

Sri Lanka is famous for many traditional crafts and among the most striking one of them is the traditional mask craft (Ves muhunu). Many crafts have been practised by certain families and the skills have been handed down from generation to generation. Mask-making too was a tradition among some families but there are also those who have learnt the trade and been faithful to it for many years.

The National Crafts Council (NCC) recently opened a Traditional Wood Carvers’ Village in Horana, in the Kalutara district to encourage and support these long-established craftsmen. The village was declared open by Minister of Traditional Industries and Small Enterprises, Douglas Devananda.

Layer by layer: Painting each mask is a complex and time consuming task. Pix by Indika Handuwela

The village was formed with the amalgamation of craftsmen from four villages- Olaboduwa, Batuwita, Bandarawatte and Mawgama. Some 60 families make their home in each of these villages and some 41 families have already received machinery and funds from the NCC with the others expected to receive support soon. The village was set up under the “Cultural Village Development Project” of 2012 with a budget of Rs.3,000,000. The National Design Centre is also a part of the effort.

Masks are made out of a wood called Kaduru (Nux Vomica) which is quite poisonous according to the National Herbarium website of the National Botanical Gardens, Sri Lanka. The latex can cause an eye inflammation lasting for two weeks. The reason this wood is used is because of its durability as it doesn’t get attacked by wood mites. Also the wood is light and easy to cut. The wood is bought by the craftsmen from Gampaha, Ganemulla and Elpitiya. Since this timber is mostly obtained from the tree trunk, the parts of the mask like the ears which requires thin planks are made out of the Albizia (Ceylon Rosewood) which is a light wood.

To carry out their work, a group of four or five mask-makers bring down a truckload of wood which is then divided among them. The next step is to cut the trunks into specific sizes and then the basic shape of the mask is drawn on the wood. The master carver then transforms the wood into the mask and polishes it to smooth the surface. It is then left to dry for about a day and then painted.

The painting is a very complex and time consuming procedure. Each colour after painting is left to dry to prevent mixing. They use

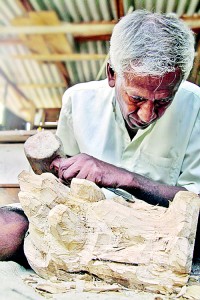

Taking shape: A craftsman works on transforming a piece of wood

bright colours such as red, yellow, green and blue and use black to draw the finer details. In the ancient days tree barks, flowers, leaves and other natural subtances were used to obtain the colours but now they use matte paints.

Karunawathi Rathuge and her husband J.A. Siriwardene have been in the trade for almost 40 years now. In 1969, there had been a big order of making around 40,000 small masks as souvenirs and that’s how many of the families of the ‘Village’ came into the trade. With a wide smile she says that ever since she married Siriwardene, she has been making masks. She specialises in wearable masks bought mostly by Thovil dancers.

“The masks that sell the best are the ‘Garayaka’ face because people hang them in their homes to ward off bad omens. Either way the market season is from August to April,” she says. Her husband is a Presidential award winner for mask making.

The biggest challenge they face is not having a special place to sell their work. Their four-inch masks, popular as souvenirs, are priced at Rs.100 and a six inch one is sold at Rs. 500. The mask that is made to be worn is a 12 inch mask priced at Rs.1, 500 and the biggest work, a 40 inch wood carving splendour is priced at Rs. 30,000.

Karunawathi is despondent that the younger generation doesn’t seem interested in these traditional crafts. The children of these craftsmen are all working in offices, factories and in other occupations so the future of the trade seems to be unclear. She has lost two sons in the JVP insurrection and has only her daughter now.

A.A. Sunil who works with his family specialises in Daha Ata Sanniya and Mayura faces, while A.A. Dharmasena specialises in making puppet faces (Rookada) for tourist areas down south especially Ambalangoda, Aluthgama and Kalutara. He has been making masks for some time with his entire family taking part in the endeavour.

District Development Assistant, B.G. Dushani Rangika has been a part of the project since its inception some two years ago. “Most of these people do this trade on a small scale. So there isn’t much capital with them. They make some masks and give them to traders. They also take orders for shops. We gave them different machines according to their needs and requests. We also gave two plants of Kaduru per household,” she said.

The tradition seems to be on the decline, but it remains to be seen how the NCC’s efforts will help these families sustain their craft amidst hardships and financial challenges.