News

Malaysian air disaster: Sri Lanka needs a crash course

Sri Lanka charges fees from aircraft entering its airspace to provide services that include search and rescue facilities. Should a disaster occur, however, the country has neither sea nor air capabilities to meet its international obligations fully.

An Australian Air Force officer looks out from an AP-3C Orion aircraft while searching for the missing Malaysia Airlines Flight MH370 over the southern Indian Ocean on March 26 (Reuters)

The suspected crash of Malaysian Airlines MH370 was a rude awakening to authorities who realised that Sri Lanka was much worse off than Malaysia when it came to disaster management at sea. Complacency, they saw, was no longer an option. The country’s search and rescue facilities are so rudimentary that the Government will have to invest heavily on aeronautical hardware and training.

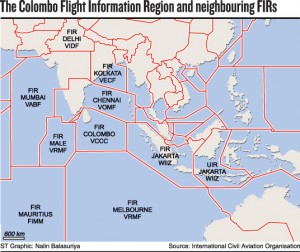

The Colombo Flight Information Region is sixty times the size of Sri Lanka’s landmass. But the country has just three off-shore patrol vessels and one Antenov An-32 high endurance aeroplane to cover a mere fraction of this sprawling expanse. None of these was acquired or is set aside for search and rescue purposes. They will be deployed on demand.

Some basic steps are being taken to improve the situation, within the means available. The overall responsibility rests with the Civil Aviation Authority (CAA). Since the MH370 tragedy seven weeks ago, the Director General of Civil Aviation hurriedly summoned three meetings to discuss inadequacies in emergency services. MH370, sources confessed, had reminded Sri Lanka of its responsibilities.

There is acceptance that the Aeronautical Rescue Coordination Centre at the Colombo Airport in Ratmalana is “somewhat defunct” and needs revival. The national search and rescue plan is being updated. “We will take into account the inventory, conduct a gap analysis and find out what we can do,” said H.M.C. Nimalsiri, Director General of Civil Aviation.

Even before the disappearance of MH370, Sri Lanka had signed agreements with surrounding countries –India, the Maldives, Indonesia and Australia –to pool resources in the event of a disaster. In March, Sri Lanka allowed over-flight clearance for special aircraft from Malaysia, Australia, New Zealand and the United States to look for MH370 in the Colombo FIR. Such cooperation is possible and will be necessary even in future.

Even before the disappearance of MH370, Sri Lanka had signed agreements with surrounding countries –India, the Maldives, Indonesia and Australia –to pool resources in the event of a disaster. In March, Sri Lanka allowed over-flight clearance for special aircraft from Malaysia, Australia, New Zealand and the United States to look for MH370 in the Colombo FIR. Such cooperation is possible and will be necessary even in future.

The Maldives is worse equipped for air and maritime disasters. To the South and South-West of Sri Lanka, therefore, are vast areas of oceanic airspace that are poorly covered – either because the two countries are insufficiently geared or because the distances are too vast for search and rescue vessels from neighbouring States to reach quickly.

Locally, there is no denial that Sri Lanka’s facilities desperately need upgrading. But where is the money? Mr. Nimalsiri estimated that one search-and-rescue aircraft could cost around US$ 60 million or more. “It must have endurance to search in the air, carry fuel, go and come back after flying to the specified area,” he explained.

Air Force Spokesman Gihan Seneviratne said the Antenov aircraft could fly 300 nautical miles (345 miles) one way, remain around 1.5 hours over a search area and alert ships to signs of wreckage or survivors. He stressed that search and rescue was not the Air Force’s primary role. Decisions with regard to upgrading facilities must be made by the CAA.

“We can only supplement what the Director General of Civil Aviation has under his purview,” he said. “The role of the Air Force is to secure the airspace for national security.”In his office, Mr. Nimalsiri projected a map of the FIR onto a computer screen and pointed to some of its sections. “We have no aircraft capable of going to this point and coming back,” he said. “Buying equipment of that value is considered unnecessary expenditure for a country like ours at the moment. Air Force doesn’t require aircraft having that range.”

Under International Maritime Organisation (IMO) regulations, Sri Lanka is also bound to assist ships or aircraft in its Maritime Rescue Zone (MRZ) which corresponds with the Colombo FIR. For the Navy, too, the MH370 disaster has necessitated a new way of thinking. At present, there is an established network of communications involving naval and other vessels such as fishing boats and commercial ships. In case of distress, messages are quickly passed around.

But the Navy does not have vessels at the ready for search-and-rescue purposes, Naval Operations Director Niranja Attygalle said. Its three off-shore patrol craft are deployed in Colombo, Galle and Trincomalee. They tackle everything from human smuggling to poaching and narcotics smuggling. And they have two weeks of sustainability; each can go out to sea for a week and return in another week.

Where aircraft are concerned, the Navy’s vessels do not have sonar equipment to detect wrecks on the seabed. “Unlike ships, aircraft will sink thousands of meters and it is impossible for us to salvage or locate,” Commodore Attygalle asserted. “At present, our ships are fitted with fish finders or depth finders, not sonars powerful enough to see a wreck at such depths.”

There is another drawback. The Navy’s three off-shore patrol vessels have capacity to accommodate helicopters on board –including decks and hangars. “But the ships came without the helicopters that could have strengthened search-and-rescue operations,” the Commodore said. “Air Force helicopters are not suitable for landing on marine ships.”

The existing OPVs are not new. One is a used vessel purchased from India in 2000. The other is on loan from India and the third was purchased from the United States at a concessionary price around 10 years ago. “We are expecting to get about two more off-shore patrol vessels from India but it will take another five or six years to manufacture them,” Commodore Attygalle said.

The Maldives, to the West of Sri Lanka, has no large off-patrol vessels. “If there is a large search-and-rescue effort, we have to invariably go for Indian assets,” explained Commodore Attygalle. “The Indian Coastguard always responds to our requests.” From the phone in his office, Commodore Attygalle can contact the authorities in any neighbouring MRZ for assistance. “We do work together,” he said. “If there is a fishing vessel in distress 1,000 miles away, there is now way we can rescue them by boat from here. We have no capacity yet.”

“This MH370 incident was a good eye-opener for many,” he agreed. “Summing up, Sri Lanka Navy can focus on or propose to higher authorities to have an embedded air wing, to acquire assets with better search-and-rescue equipment.”Experts pointed out that Sri Lanka would need to make a colossal investment on facilities that might not be used for many years. “But the day you want to use it, there is nothing,” said one. “That is the issue.”

Civil Aviation Dept. fears HR shortage

News that two of the Civil Aviation Department’s most senior officials have sought employment in Dubai has raised fears of a human resources shortage in the highly-specialised industry.

Director General of Civil Aviation (DGCA) H.M.C. Nimalsiri and Senior Director Parakrama Dissanayake on April 20 attended interviews for the post of Adviser to the DGCA of Dubai. Neither has been informed yet of the outcome but authoritative sources said one of them is likely to secure the job.This will leave the Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) with one less senior officer amidst a staffing crisis stretching back some years. CAA sources said that the Authority has already lost 9 civil aviation inspectors in less than three years.

International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO) records show that Sri Lanka’s level of compliance with global requirements was well above world average in all sectors, particularly safety oversight. The only low score recorded, at 55.12%, was in personnel and training.

Mr. Nimalsiri accepted that there were difficulties recruiting and retaining specialised staff. “The people we recruit don’t have industry experience,” he said. “Unless we take from the industry and give regulatory experience, we might not be able to train from scratch. If we start producing (such personnel), they get better opportunities abroad and leave.”

West Asia, with its expanding airlines and competitive salaries, was a major pull factor. “I lost six air ordnance engineers in the past three years,” Mr Nimalsiri said. “In a way, it is a good development because they are making money and sending foreign exchange back to the country. But at the same time, we cannot afford to train people just for them to leave. It is expensive.”

Mr. Nimalsiri said he had not applied for the post of advisor to DGCA Dubai in competition with his junior. Having decided that he might wish to leave the CAA after 27 years, he had given his curriculum vitae to an industry colleague. “It ended up with me being called for an interview in Dubai,” he said, adding that he would not have gone if he had known that Mr. Dissanayake had applied for the same post.

Authoritative sources confirmed that Mr. Nimalsiri had conveyed to Civil Aviation Minister Priyankara Jayaratne, his desire to resign. But Minister Jayaratne, who last week denied this outright, had refused to accept it.When the Sunday Times questioned Minister Jayaratne about Mr. Nimalsiri’s resignation, he denied that he had ever heard of it. Sources said the ministry was trying to suppress the information because it was known finding a replacement would be a difficult task.

Asked whether he would take the job if he got it, Mr. Nimalsiri said, “Yet to be determined.” He also said he would subject himself to the wishes of the Cabinet in this regard. “I will not let this organisation down,” he stressed. However, he is due to retire in four years.