Sunday Times 2

How India’s iconic Gandhi cap has changed sides

India’s Congress party, fighting an uphill struggle to return to power in the current elections, has the Gandhi family on its side, and Rahul Gandhi leading its campaign — but the iconic Gandhi cap has changed sides.

This simple white cap, a bit like an upturned boat, has made a political comeback in India’s election campaign.

Once regarded as dated and distinctly uncool, it’s now back in style – and indelibly associated with the upstart force in Indian politics, the anti-corruption Aam Aadmi (it means common man in Hindi) Party.

Aam Admi Party leader Arind Kejriwal

It was Mahatma Gandhi, the great campaigner for self-reliance and social justice, who made the Gandhi cap famous. And the Nehru-Gandhi family (no relation to Mahatma Gandhi) initially co-opted it.

But the party now dishing out tens of thousands of these cheaply made caps emblazoned with party slogans at rallies across India has as its election symbol the traditional household broom, because it wants to sweep away what it sees as a corrupt political system and Congress and the other parties allegedly complicit in that system.

Competing claims

There are competing claims as to the origins of the Gandhi cap.

Historians believe they lie in Gandhi’s initial excursions into non-violent protest in South Africa before the First World War. Gandhi and other jailed Indian protesters were obliged to follow the dress code of black prisoners, which included the cap that Gandhi was to make his own.

When Gandhi returned to India, he adopted the custom of wearing clothes made with homespun “khadi” cotton. Along with the cap, this became the uniform of the self-reliance movement. In the early 1920s, the Gandhi cap was sold at political meetings across India, much to the fury of the Imperial authorities.

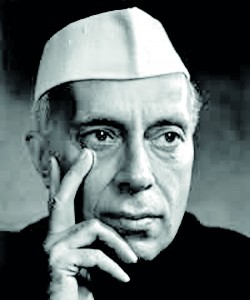

sporting the Gandhi cap, the signature headgear of Jawaharlal Nehru

“The British,” says historian Lata Singh, “began to clamp down on Gandhi cap-wearers by dismissing them from government jobs, fining them and at times physically beating them.”

Mahatma Gandhi’s style of dress became firmly associated with the nationalist movement, and — by association — with the Congress party.

The suave Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first prime minister, habitually wore a smart version of the Gandhi cap. So did several of his successors. But over decades, it faded out of fashion.

Its political revival came with the rise to prominence in 2011 of the anti-corruption activist, Anna Hazare.

He adopted one of Gandhi’s hallmark methods of campaigning, the public hunger strike, and his choice of headwear further strengthened the association with the man India knows as “Bapu”, the father of the nation.

Political fashion

When the Aam Aadmi Party was founded in November 2012, its leader was another energetic anti-corruption campaigner, Arvind Kejriwal. He too made a point of wearing the Gandhi cap. A political fashion had been set.

At the end of last year, this new party stunned the political establishment by winning 28of the 70 seats in the state assembly covering the Delhi area. Arvind Kejriwal himself briefly became the state chief minister.

The dramatic success of the AAP, harnessing the support of the hitherto anti-political Delhi middle class and of the urban poor, meant an even more emphatic return to style of the cap its leaders wore.

It had become the “new fashionable item of radical chic”, according to the austerely left-wing Economic and Political Weekly, sported by Bollywood film stars and co-opted by fashion boutiques.

From humble headwear to haute couture, from political emblem to style accessory, the Gandhi cap had undergone quite a transformation.

In this election campaign, Mr. Kejriwal and his AAP, lagging far behind the main parties in resources and grassroots reach, have used two symbols to rally support – the broom and the cap. At campaign rallies and when supporters are out canvassing, the cap has become the party’s calling card.

Whether the “aam aadmi” version of the Gandhi cap will be a fleeting fashion or achieve political staying power is for India’s voters to decide.

(Courtesy BBC)