The rise and fall of Gaspar de Figueira de Cerpa, the ruthless Portuguese Captain

Throughout the siege of Colombo that lasted more than a year, a colourful character emerges in the form of a brave, ruthless soldier of mixed parentage. Rebeiro sets aside several pages of his narration for this soldier who is depicted as a hero, saviour and a dedicated Christian. Born to a Portuguese father and a Sinhalese mother, Gaspar Figueira de Cerpa was brought up in the Portuguese tradition and lived in the suburbs of Colombo. Knox describing the Portuguese soldiers remaining in the island after his escape from Rajasimha’s territory explains why this Captain Major was so named. “..Gaspar Figueira would hang up the People by the heels, and split them down the middle. He had his Axe wrapped in a white Cloth, which he carried with him in to the field to execute those he suspected to be false to him, or that ran away. Smaller Malefactors he was merciful to, cutting off only their right hands. Several whom he hath so

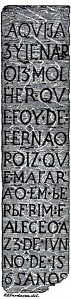

An old Portuguese tombstone dug up near the site of the Battenburg battery in the fort of Colombo when the breakwater works were begun. It bears the inscription “Here lies Helena Roiz who was wife of Fernando Roiz, whom they murdered at Berberim (Beruwala). Died on the 23rd of June in the year 1565”. Pic courtesy Twentieth Century Impressions of Ceylon which reproduced it from the Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society ( Ceylon) xviii.2,375.

served, are yet living, whom I have seen”.

His ruthlessness surpassed that of the fellow, a baptized natural Sinhalese, Simon Carera who exercised great cruelty to Sinhala people with punishments like making women beat their own infants in mortars they used to beat their corn. Figueira de Cerpa is the very same soldier who made an expedition to Kataragama with the idea of plundering the wealth of the Temple. Rebeiro describes how the Sinhala villagers who came up to help them find the path to the shrine became ‘possessed’ and how de Cerpa beheaded them mercilessly. According to Rebeiro this soldier was inside the Colombo fort when it fell to the Dutch and Sinhala forces.

What is interesting about this individual is not only his military prowess and fearlessness but a legend built around him that was immortalised by a ballad, popular among the ordinary folk at the time. R. L. Brohier, in his article entitled, “Vignettes from the past – III- Legend of de Figueira immured Alive”, that appeared in the Journal of the Dutch Burgher Union of Ceylon, records the legend as told by Louis Nell, Queen’s Advocate and one time editor of the old English paper, “The Examiner” . Louis Nell was Dr Andreas Nell’s father.

“..It was between 1869 and 1871 that labourers with pick, alavangu and mamotie undid the solid work of many weary years, which the Dutch had devoted after the capture of Colombo (12th May 1656) and which no enemy guns ever attempted to break down. The moats were filled with the rubble from the fortifications. At the end of York Street, and near that part of fortification known as Rotterdam Bastion, there once stood an old casemated Powder Magazine which singularly was spared for a few years longer to recall a weird traditional tale of dark tragedy”.

It was known, as Rebeiro had repeatedly recorded that large numbers of Portuguese including senior captains and their Christian retainers deserted the fort to the enemy because of the travails already described. This story begins with the last days of the Portuguese era when a deserter escaped into the Dutch camp and offered to divulge the ‘weak’ spots of the ramparts and the bastions that were poorly defended so that the Dutch could easily break into the fort. In exchange for this favour he appealed for being adequately rewarded if his information proved correct. The Dutch Commander accepted the offer and attacked the said weak spots that eventually led to the capitulation of the fort.

According to this legend narrated by Nell, the deserter was Gaspar de Figueira de Cerpa, the ruthless half-caste soldier who Rebeiro so painstakingly pictured as a hero. The readers would recall that this name cropped up on several occasions in this article. Once the surrender was successfully concluded de Cerpa demanded the reward for his part in the Portuguese defeat. The Dutch Governor harangued de Cerpa on the enormity of the offence of having betrayed his own countrymen and as a warning to all traitors sentenced him to be locked up on the top of the powder magazine.

The sentence was carried out accordingly and de Cerpa was taken to the sentry box like vault on top of the powder magazine. A loaf of bread and a bottle of wine were placed inside and the entrance was built up and the unfortunate de Cerpa was immured alive.

Brohier quotes, J. P. Lewis writing in the Ceylon Antiquary and Literary Register, (Vol. I, Part-III, 1916), as saying, “…I myself distinctly remember the sentry box like structure associated with this tradition …when I first knew Colombo in 1877”. It is recorded that the spot stood between the site on which the old Surveyor General’s office came to be erected and the Echelon Barracks and was not demolished but later covered up at the time the surface of the whole area was raised. Lewis supplied eleven verses of a popular ballad based on the story with the hope that someone else who had the other verses would record them. According to Brohier this was a forlorn hope for the melodious vernacular which was much in vogue among the poor and the struggling lower middle class populations – the tinker, the tailor, the cobbler and the coffin maker – has since ceased to be spoken and with passing away of this community its very traditions are forgotten.

Two important and somewhat reliable sources provide information regarding de Cerpa being taken prisoner by the Dutch at the time of Portuguese capitulation of the Colombo fort. Rebeiro certifies that de Cerpa was in the fort during the last days of the siege. He also mentions that large number of Portuguese and Christian soldiers including Captains deserted the fort. Rebeiro however does not name de Cerpa as one officer included in the 73 haggard men that came out of the fort on the 14th of May 1656. However, according to Rebeiro some of the Portuguese Captains who surrendered to Hollanders in Colombo and were subsequently taken to Nagapatam returned to the Portuguese held Mannar and Jaffna with the intention of hanging on to their last few possessions of the island. Unfortunately for them it was just a pipe dream as the Portuguese surrendered Jaffna to the Hollanders on the 24th of June 1658. Rebeiro specifically says that de Cerpa was one of the fidalgos and chief people that marched out of the Jaffna fort.

If de Cerpa was actually one of the deserters as the legend says, perhaps Rebeiro was too embarrassed to record it after glorifying his military prowess. On the other hand there is another possibility – that the central character in the legend and the ballad is not de Cerpa but another Portuguese retainer of high position who later deserted the fort. Rebeiro distinctly mentions that de Cerpa was taken prisoner by the Dutch and was deported to Goa where he died. He also records that Rajasimha II who shared the victory over the Portuguese with the Dutch appealed to the Dutch commander to give him de Cerpa. Knowing the impeccable military record of deCerpa , Rajasimha’s idea was to make him his army commander. It is said that both the Dutch and de Cerpa dismissed this appeal.

Brohier says, “… it is curious that tradition has elected to brand him a traitor and assign a more tragic ending. Written history does not tell how he died but the tradition which has come down the corridors of time in a popular folk ballad seems to have originated from his own people left in Ceylon, the Porto-Sinhalese and was rendered in the corrupt Portuguese patois they bequeathed to Ceylon”.

Could this character be someone else that was half caste or natural Sinhalese baptized and working for the Portuguese? Knox speaking of the Portuguese in Ceylon at the time mentions another person who was a born Sinhalese but baptized who also was the central figure in a popular ballad. This person was Lewis Tissera. Apparently Tissera swore that he would make the king (Rajasimha II) eat, according to Knox, the worst fare of the island. But the king took him prisoner and bound him with chains and made him eat the same fare. He further says, “… That there was a ballad of this Man and this passage, Sung much among the common People there to this day”. But it is obvious that this ballad is regarding how Tissera was forced to eat kurakkan thalapa and not in any way connected to an immurement.

Another possibility is that the origin of the legend was a hoax designed by the Dutch themselves. It has been recorded by several historians that the actual condition of the Portuguese-held fort was not known to the Dutch or the Kandyans. The stories of horror and hunger described by deserters were too grave to be believed by any outsider. It is recorded by Rebeiro that the capitulation was conducted ’honourably’ and the Dutch could not believe their eyes when seventy three bedraggled men walked out in surrender. Knowing the military prowess of de Cerpa and to hoodwink Rajasimha who kept on demanding de Cerpa to be handed over to him, the Dutch would have clandestinely shipped the defeated Captain Major to Goa as recorded by Knox and Rebeiro. The story of punishing a traitor and the subsequent sentence in the form of an immurement would have been spread by the Dutch themselves.

The central character in the legend described by Nell and in the ballad recorded by Lewis is definitely a Portuguese Captain whose identity remains buried in the annals of history of the island nation. The immurement immortalized in this long lost ballad brings back the memories of the fate of the builder of the Kala Wewa, the great King Dhatusena. Dhatusena was immured on the banks of his beloved Kala Wewa by his son while Gaspar de Figueira de Cerpa, the ruthless Portuguese Captain had to die in a sentry box plastered over by the Dutch as a punishment for being an enemy informer who was of no use to them anymore.

(The writer is attached to the Faculty of Medicine and Allied Sciences,

Rajarata University of Sri Lanka, Saliyapura)