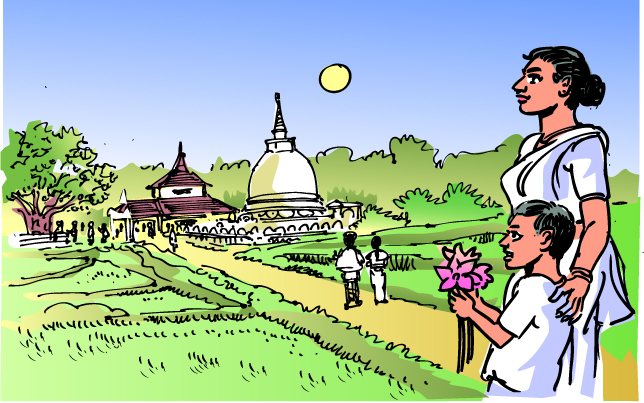

Vesak in the village

Going back six to seven decades, I recollect how Vesak was celebrated in the village temple. I remember how I used to accompany mother to the temple along the paddy fields to the ‘Sabahve pansala’. (I never bothered to find out how the temple had got that name).

Poya day then was another working day for everybody. So the crowd in the temple on a Full Moon day was limited to a handful, mostly the old folk –mainly women .

Vesak was different. Being a public holiday, that was one day when a large number of villagers spent the day at the temple. The sound of the temple bell at the crack of dawn signalled it was time to get to the temple. Clad in white with the’sil redda’ on top of the shirt or the jacket the villagers would go to the temple and gather around the Bodhi tree to observe ‘ata sil’ –– the Eight Precepts from the ‘loku hamuduruwo’. The parents invariably brought their children along to get them used to the Buddhist way of life.

After observing ‘sil’ they prepared the ‘Buddha-pooja’ to be offered to the Buddha in the ‘budu-ge’ where the main statue of the seated Buddha is located. It was a ‘podi hamuduruwo-, a junior monk who conducted the pooja getting the devotees to repeat the stanzas after him. This ritual is continued to this day in all temples.

Unlike today when the ‘sil’ programme is conducted on a planned basis, in the bygone days there wasn’t a schedule as such. Once the Buddha pooja was offered they gathered at the ‘bana maduwa’, spread mats and got ready to listen to ‘bana’ .The first sermon would be on the significance of Vesak when the monk would sum up the birth and life of Prince Siddhartha and move on to his leaving the palace, his search for salvation, the Enlightenment, wandering, preaching to the people after attaining Buddhahood, and the passing-away. There was plenty of feeling and emotion thrown in particularly about the difficult times he led during the ‘duskara kriya’period when he was reduced to skin and bone.

In between the sermons an elderly ‘upasaka mahattya’ would read a Jataka tale from the ‘Pansiya Panas Jataka Potha’ containing 550 tales of the previous lives of the Buddha. Others would gather round him and listen.

Though there is so much accent on meditation today, not so much attention was paid to meditation then. The monk would touch on the subject briefly and get the devotees to close their eyes and concentrate on spreading ‘metta’ to others.

When it was time for the ‘daval dana’– the main alms – to be offered to the monks, arrangements were made early to offer the Buddha pooja and then serve the monks who have to finish consuming solid food for the day before noon. A few families would bring the rice and the curries with a few fruits and sweetmeats for dessert. The devotees would bring their own food. They would sit under a tree and eat.

The youngsters who had not observed ‘sil’ would spend the afternoon getting ready for the big event of the day – the evening ‘perahera’. The boys would watch them and help them in numerous ways. Leading the way would be the cyclists with decorated poles tied to the bicycles. Boys carrying flags marched in single file behind the cyclists who went at a slow pace meandering on the road. A couple of drummers and a few dancers added colour to the procession as did the ‘boru kakul karayas’ – the stilt walkers who were a big attraction with most of the onlookers by the roadside wondering how they kept their balance. The man on the ‘ katu imbul gaha’ – a branch of a tree with lot of leaves and a few thorns – was carried in a bullock cart to demonstrate the fate of those going to hell! Little ones were mesmerised by the man who climbed up and down the tree trying to avoid being hurt by the thorns.

The procession would return to the temple in time for preparations for the final sermon. A couple of gram sellers would have gathered near the temple gate. Flowers were never sold. Every household brought flowers sufficient for the day’s offerings.

The ‘mal vatti vendesiya’ started well ahead of the sermon when flowers arranged in ‘vattis’ were auctioned. There would be brisk bidding by the devotees with the smaller ‘vattis’ going for low amounts until the climax when a big flower arrangement was auctioned. By this time the village ‘mudalais’ would have come in and started bidding. The ‘auctioneer’ would keep shouting the bid every now and then stopping and yelling ‘aavarai….. devarai…’as if the auction is over. He stopped for a while when he heard someone raising the price by another five cents. The auction finally comes down to two and sometimes becomes a prestige issue with one ‘mudalali’ not wanting to be outdone by the other. The ultimate result is what matters and the whole exercise was to collect funds for temple work since there were no big benefactors in the village those days. It was also not the practice for the head monk to go round asking for money. The monks were quite contented if they got their alms and had enough to maintain the temple.

A monk from another temple would deliver the last sermon. One of the senior ‘upasakas’ would sit close to him on the ‘pedura’ and keep repeating ‘ehei’ at the end of every sentence the monk uttered.

It would be quite late when the sermon ended. Some of those who observed ‘sil’ would spend the night in the ‘bana maduwa’. Others returned home by the light of the full moon.