Sunday Times 2

Don’t dare pee in a pool again!

An urban myth, spread by parents around the world to stop their children peeing in the pool, claims urine turns swimming water purple.

Although this isn’t the case, a firm from Texas has created a device that builds on this premise to detect traces of human waste in liquids.

The container adds zinc ions to water that then glow if urine or faeces is present in the sample.

The technology was developed by researchers at Texas A&M University, led by Vladislav Yakovlev.

Traces and extremely small indicators of waste matter, claimed Yakovlev, have been traditionally difficult to detect but can signal greater levels of contamination, which can lead to illness and even death.

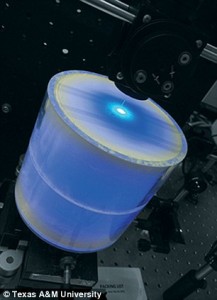

The device, pictured, adds zinc ions to water that glow if waste matter is detected. It does this using lasers to react with a byproduct called urobilin. Pic courtesy Texas A&M Universtiy

Yakovlev and his colleagues’ device works by detecting a chemical known as urobilin.

Urobilin is a byproduct released in the urine and faeces of many mammals, including humans and livestock such as cows, horses and pigs.

Urobilin molecules are small and diffuse quickly so they easily occupy large volumes, such as lakes and reservoirs, for example.

When mixed with zinc ions, urobilin forms a phosphorescent compound which glows green under an ultraviolet light.

In some samples, however, with low concentrations of urobilin, the phosphorescent emission, can be weak, making it difficult to analyse the sample.

To tackle this, Yakovlev and his team developed technology that ‘excites’ extremely small amounts of urobilin in large samples of water to make the glow stronger using what’s called an integrated cavity.

The integrated cavity is a hollow, cylindrical container.

A water sample is placed inside the cylinder where it interacts with zinc ions, and a laser light is beamed into the object and onto the sample through a small hole.

The light reacts with the urobilin compound in the sample, causing it to emit a glow.

Using the cavity, Yakovlev and his team have detected the presence of urobilin down to a nanomole per litre.

A mole is a common unit of measurement in chemistry, and a nanomole is one billionth of that measurement.

What’s more, the technology provides actual concentration levels of the contaminant, and it does so almost instantly.

Yakovlev and his team are now working to commercialise the technology for urobilin detection.

The technology could also be used for detection of other types of toxic compounds in both liquids and gases, lending itself to anti-terrorism applications, among other uses.

© Daily Mail, London