A building must belong to a city not just the owner

Like his father, and his father’s father, and his father’s father’s father before him, Juan Pablo Serrano Orosco is an architect. Each generation has passed down to the next not only a knack for the work but a passionate dedication to it. “Architecture is a way of life, from the moment you start, till you go back to bed, it’s an architectural life.” Sitting by his son’s side is J. Fransisco Serrano and

In Bawa’s Colombo residence: Juan Pablo Serrano Orosco and J. Fransisco Serrano

surrounding them both is Geoffrey Bawa’s beautiful home in Colombo. They’ve just returned from the gardens at Lunuganga and are an hour away from delivering the Geoffrey Bawa memorial lecture for 2014 when they sit down with the Sunday Times for a quick interview.

Though he grew up around building sites and architectural plans, Juan says he really found his calling when he discovered the intersection of architecture and computing in university: “I really started to be an architect in my first year with my friends in university.” In their company, he made the transition from what he calls a normal life to an architectural life and learned to “look at cities in a different way, to look at buildings or even your own house with a new way of seeing.” Like his son, Mr.Serrano did not at first intend to be an architect – his interest was in chemistry – but a career guidance test pointed him in the direction of a profession which he can now admit was always in his blood. “I grew up on jobsites. I used to go and jump on the sand piles, be a friend of the masons. I had a life very close to construction.” he says.

This intimate, personal connection has afforded this family a ringside view of the development of architecture in modern Mexico – their chosen subject for the memorial lecture. “Mexican architecture has a quality that isn’t always seen,” says Mr. Serrano. “This quality is that we respect very much in our culture.” He believes this awareness dates as far back as the likes of the Aztecs, the Mayans and possibly the oldest of them all, the Olmecs who lived and died somewhere between 5100 – 400 BCE. (These ancient influences are not hard to trace in the work of Mr. Serrano. Some of his most magnificent buildings such as Mexico City’s Federal Courts or the Mexican embassy in Berlin borrow that sense of scale, inspiring awe with majestic proportions and soaring facades.) Then there are the architectural footprints of the colonialists and the innovations of a legion of contemporary architects that have contributed to what we consider ‘Mexican’ architecture today. “We start seeing that especially when people from other countries come and say ‘Serrano, this can only be done in Mexico.’”

When the two men began their lecture at SLFI last week, they did so by acknowledging the similarities they saw between Sri Lanka and

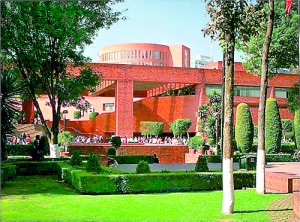

Designing with a strong sense of culture: Buildings by J. Fransisco Serrano and Juan Pablo Serrano Orosco (above and below)

Mexico – placed along the same latitude, they are both tropical countries with plenty of coast and a tendency toward heat and humidity. (“We are maybe a little bigger,” Juan said tongue in cheek.) Father and son have practised together and apart, and so they showed their work in three segments. Even though the uses these buildings were put to varied widely, it was clear their philosophy remained  consistent across their oeuvre. Juan tries to articulate it: “A thing that we preach is that there is a relationship between the interior and exterior, between your weather and the construction, there is a relationship between materials.” He believes architects must be sensitive to the “poetics of the space, the tectonics of the space.”

consistent across their oeuvre. Juan tries to articulate it: “A thing that we preach is that there is a relationship between the interior and exterior, between your weather and the construction, there is a relationship between materials.” He believes architects must be sensitive to the “poetics of the space, the tectonics of the space.”

This awareness must now be made compatible with sustainable design and this focus is moulding the most recent wave of Mexican architects. While for Juan it is a recent (if necessary) trend, for Mr. Serrano, this is what clever architects were doing all along. “My father was a pioneer of those things in Mexico,” he says, explaining that these precursor structures already favoured natural ventilation, used hollow walls for temperature management and placed the water up high on the roof,  simultaneously heating and reducing the burden on the pump.

simultaneously heating and reducing the burden on the pump.

If anything, the family’s philosophy has expanded since those days. They now design not just for a single customer but for the community around as well. In fact, they believe a building doesn’t belong just to its owners but to the entire city. “It’s important to take care of the sustainability, the quality of life of people not just inside the buildings but outside the buildings, in public spaces,” says Juan. “Before architecture was just isolated art, but now everything has merged.” Mr. Serrano adds: “The marks that architecture gives the city are unforgettable.”

Now as they prepare to return home, father and son voice their gratitude for opportunities such as these that have allowed them to see the world through the eyes of other architects, people as committed to the ’architectural life’ as they are. They have particularly loved their sojourn in the house that Bawa built. Mr. Serrano is especially pleased because he remembers meeting Bawa in the ’60s, and knew him even then as the “guy of the beautiful gardens.” Juan adds:“It is an honour to be here, to feel things Bawa felt. The whole experience is complete, being in the same place as him.”