Both personal and political

When working at a newspaper, persistently immersing yourself and constantly engaging in a world of words is inevitable. “The sum total of human knowledge is a speck of dust compared to the universe of our ignorance,” says Malinda Seneviratne slowly, explaining that the learning which takes place on a daily basis wards off any saturation or word-weariness that may be an occupational hazard of this engagement.

Malinda: “Journalism or poetry, I have things to say one way or the other”

Fresh from his win at the Gratiaen this year, we meet Malinda Seneviratne, Editor-in-Chief of The Nation. Previously nominated for the Gratiaen Prize four times and also winner of the 2011 H.A.I. Goonetileke Prize for translation, Malinda was drawn to poetry long before he wandered into what has become his profession now, and remains candid about the ebb and flow of both spheres. “Journalism puts you right up face-to-face with things that maybe not everyone has to deal with sometimes. It’s a very close engagement with people and events and processes […] when I write poetry it’s that environment of being that I create. I can’t draw the lines and the arrows, this way and that way. It’s the universe I inhabit. So there is obviously some outflow or some impact or influence.” “It’s the same human being that is doing both,” he shrugs explaining that poetry and journalism share the same vein of pragmatism and the only difference was the seemingly task-oriented nature of one over the other, “That is one form and this is one form. I have things to say, one way or the other.”

A love for literature began at home and was simultaneously carefully and carelessly inculcated by his parents – “They didn’t try to make us fall in love with words, but they left enough words around for us to trip on, pick up and play with.” In his acceptance speech at the Gratiaen Award ceremony, he mentioned that his father gave him words, while his mother gave him heart. “In terms of the creative ability I think I got more from my father,” explains Malinda, “but my mother was a good hearted and very generous human being, I think I learned more about the human condition by experiencing my mother’s life at close quarters and the way she dealt with people.”

Educated in Sri Lanka and at Harvard University (“That was an accident. I was at university at a bad time and the universities closed and I just applied, got a scholarship and went”), he returned to Sri Lanka, did a few jobs, got into a bit of trouble and then went back to the States to study at the University of Southern California, and later for a PhD at Cornell University which he abandoned after completing all the coursework. “We grew up in a time where we never had career plans. Studying seemed like a logical thing to do. Sociology was something I liked. So I did that […] I wanted to a do a PhD because I thought that graduate school would give me more focus and I thought a PhD would be a useful title for political purposes.”

Malinda speaks about his poetry with an almost self-deprecating candour. “Nothing spectacular or unique in what I write about. It’s what almost everyone writes about in the end,” he asserts. “They are approached, I like to think, from a philosophical point of view which is mostly influenced by my understanding of Buddhism and is a frame that gets naturally imposed in my explorations.” For Malinda, poetry is prompted by various needs. Sometimes a poem is needed to decorate a page or accompany a photo-essay being published in the paper. Sometimes, poetry works as tangible strands of thought using paper and ink: “Poetry is in a sense an exploration, sometimes if you want to clarify something or reflect and make sense of something, writing helps”.

Malinda speaks about his poetry with an almost self-deprecating candour. “Nothing spectacular or unique in what I write about. It’s what almost everyone writes about in the end,” he asserts. “They are approached, I like to think, from a philosophical point of view which is mostly influenced by my understanding of Buddhism and is a frame that gets naturally imposed in my explorations.” For Malinda, poetry is prompted by various needs. Sometimes a poem is needed to decorate a page or accompany a photo-essay being published in the paper. Sometimes, poetry works as tangible strands of thought using paper and ink: “Poetry is in a sense an exploration, sometimes if you want to clarify something or reflect and make sense of something, writing helps”.

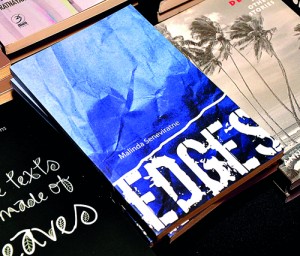

The Judges for the 2013 Gratiaen Award commented on Malinda’s use of the personal and political in ‘Edges’, the collection of poetry which earned this year’s prize. “We are always both,” he says, elaborating that politics permeate all of our actions. “I don’t put a collection together and say ‘ok, this is going to be 50/50’. Poetry doesn’t get written according to a recipe in terms of subject matter or a mix of the political and the personal. I think that distinction is also false,” opines Malinda adding that at times political moments both inspire and provoke a poetic response.When writing journalistic pieces, topicality, relevance, audience and subject matter are all factors which are deliberately weighed in but “poetry”, asserts Malinda, “is a very personal, vain thing in the end. And if others can relate to what you write in some way, then you have a community. But if you were to write to an audience, that is like pamphleteering. I’m not going to do that.”

Social Media has been an important tool both for expression and engagement for him -“I don’t know where my words will end up.” While describing the act of sharing one’s poetry with an audience as the equivalent to opening the door to your bedroom, the community that is created and the feedback received from varied parts of the world has been useful.

While poetry is never planned, it is translations which are taking predominance in his life these days. Malinda, who was the recipient of the 2011 H.A.I Goonetileke prize offered by the Gratiaen Trust for his translation of Simon Navagaththegama’s “Sansara Aranyeye Dadayakkaraya”, speaks avidly about the profusion and quality of Sinhala and Tamil literature in the country and the lack of good English translations of the same. He reaches out for a well-worn copy of Mahagama Sekara’s “Prabuddha” tucked in his laptop bag, which he is now in the middle of translating. Language is both a boon and a bane when filling the fissures between one’s knowledge and lack of it, as well as trying to do justice to the original work. Translations of Sarathchandra’s “Malagiya Attho” and “Malawunge Avurududa” are also on the cards for their sensitive exploration of love.