Sunday Times 2

25 years after the fatwa: Rushdie’s fight for free speech

Considering the timing, it’s a pity Salman Rushdie isn’t giving interviews. It’s been 25 years since the fatwa that turned his life inside out was issued by the Ayatollah, it’s been 10 years since he founded PEN World of Voices Festival in response to 9/11 and it’s been two years since ‘Joseph Anton’, a memoir about his life as a fugitive writer, found its way to bookstores. 2014 itself will not be without milestones. After a decade-long stint at the head of World of Voices, Rushdie stepped down, declaring on the festival’s opening night in New York City recently that “there was something a little North Korean” about being chairman for life.

Journalists watching may have itched for 10 minutes with the celebrated winner of the Booker of Bookers but those taking notes from a distance were still rewarded with a few incendiary quotes. Rushdie, this time circumspect in respect to his own life and work, chose instead to focus on issues of media censorship and the ever multiplying challenges to freedom of expression – and he made it more than clear that he considers India’s new Prime Minister elect among the latter.

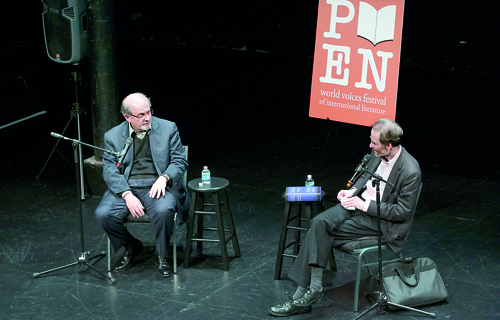

At the PEN Festival: Salman Rushdie and Tim Garton Ash. Pic by Beowulf Sheehan

In April, Rushdie was among a number of artistes and academics to sign a letter expressing ‘acute worry’ over the Hindu nationalist party’s expected victory in India’s general elections. In a short address at the festival’s opening, the Indian born author described Narendra Modi as a “highly divisive figure” and a “hardliner’s hardliner”.

“Democracy is more than mere majoritarianism,” he said. “All citizens must feel free all the time, whether or not they end up on the winning side of the election.”

Introducing him at another talk on the final day of World of Voices, Timothy Garton Ash pinpointed why Rushdie’s word is lent credence on such matters. He described the author as someone who is “both a symbol of the defence of free speech, and has been for a quarter of a century, but is also intensely, personally engaged in the struggle for freedom of expression.”

Remembering the moment when he was told that a fatwa had been issued, Rushdie paused to imagine what a difference six months would have made – the book was published in the September of 1988, then on February the 14 Ayatollah Khomeini presented Rushdie with his murderous “Valentine’s day gift,” only to meet his own end in the June of 1989. A few months delay in sending ‘The Satanic Verses’ to print, a book more than one critic has dismissed solely on the basis of literary merit, may have led to it slipping by unnoticed and under the radar as one of the lesser entries in Rushdie’s canon.

But that is not what happened.

Twenty years after the book burnings and the boycotts, after the death threats and the assassination attempts, a few journalists in Britain marked the anniversary of the fatwa by setting out to interview Muslims in the country who had participated in protests linked to it. They found that many had recanted, some because they believed now that free speech was worth defending even if Rushdie was not, but others for more tactical reasons. ” ‘It hadn’t worked, it had backfired,’ they said. It had made the Muslim community more disliked and it had made me more famous and more wealthy.”

In 1993, four years after the fatwa was issued, Rushdie made his first public appearance. He appears comfortable now in his role as a literary celebrity, but of course the years he spent in debilitating fear for his life and the lives of those around him, forcefully separated from family and friends, constantly shuttling between safe houses, are not as easily shrugged off.

When asked by Garton Ash if he felt they had won a victory, Rushdie’s response was both yes and no. A narrow focus, he said, would look at the attempt to ban the book, the attempt to intimidate its publisher, the attempt to coerce its booksellers and translators and the attempt to murder its author – most of which came to nought. (The horrifying exceptions being the murder of the Japanese translator, the Norwegian publisher who survived being shot thrice in the back and the Italian translator who was stabbed, left for dead and lived to tell the tale.) On the other hand, by Rushdie’s last count, ‘The Satanic Verses’ was available in 48 languages and is still in print in all of them. “If you look at the actual small narrative of the events surrounding The Satanic Verses, we didn’t do so badly…The publishers, give or take, held the line. We defended what there was to defend…And you know, the author is still here too.”

Still, winning the battle has made the war so much more challenging to fight. On a larger scale, he believes it has made anything critical of Islam that much more difficult to publish. “These encroachments of free speech have become constant,” Rushdie said. “It’s this idea that is gaining more and more traction that people have the right not to be offended. People don’t have the right not to be offended, because all sorts of things, offend all sorts of people. And if we all had the right not to be offended by anything that offended us, nobody could say anything. I don’t like the novels of Dan Brown, but I think he should live. I’m not sure about publish, but live.”

Halfway through the conversation, he made a leap, using a hit show currently running on Broadway as an example of an enlightened response: ‘The Book of Mormon,’ is utterly irreverent but has not given the kind of offence you’d expect. Elders of the Mormon Church were invited to an early screening (“and they go around saying, ‘very funny show’”) and the Church later bought advertising space on the playbill which read, ‘You’ve seen the play, now read the Book.’ “That’s what you call being grown up,” said Rushdie.

He’s not been able to say the same of those involved in forcing the iconic artist MF Hussain to spend the last years of his life outside India or who had A. K. Ramanujan’s seminal work ‘Three Hundred Ramaya?as’ scrubbed from the History syllabus of the Delhi University or who most recently accused the writer Wendy Doniger “ludicrously and ungrammatically” of ‘being a woman hungry of sex.’ “Episodes such as these are multiplying by the month it seems, by the day almost, and the authorities have failed lamentably to protect free speech rights,” Rushdie said. All his own years of persecution have made this to him an almost sacred thing.

Rewind back to opening night: Rushdie kept his speech short, but found time to read from a poem by Rabindranath Tagore that I remember memorising as a child. To hear it read again, so far from home, was unexpectedly moving. The poet speaks of a place ‘Where the mind is without fear’, ‘where the clear stream of reason has not lost its way/ Into the dreary desert sand of dead habit,’ and concludes, ‘where the mind is led forward by thee/ Into ever-widening thought and action/ Into that heaven of freedom, my Father, let my country awake’. Rushdie’s final line, after which he folds up his speech and leaves the podium, lingers, held there by the force of his conviction: “India is in danger of betraying the legacy of its founding fathers and its great artists like Rabindranath Tagore.”