Skills development: From prejudice to prestige

It is not difficult for you and me to find a contractor (Engineer) to construct a house. But it is near impossible to get an electrician, a plumber, a carpenter or a handyman for a small repair in your house. If you and I are asked to decide the professin (vocation) for our child we would be very prompt and say ‘civil engineer’. We would not even imagine our child to be an electrician, a plumber, a carpenter or a handyman. This is the prejudice against skills development training or popularly known as technical education and vocational training (TEVT) and the prestige built up for higher education (academic training) in our country. Of course dying with prestige is more important than survival for us Sri Lankans.

Sri Lanka is already a lower middle-income economy with a Per Capita Income (PCI) of US$3,300. It is aspiring to achieve a PCI of over $4,000 in year 2015 with a minimum average annual growth rate of 8 per cent. The country is transitioning from a factor driven to an efficiency driven state. These anticipated upward positive changes in the economy call for the presence of a competent skilful labour force. This is explicit as a priority in Mahinda Chinthana – Vision for the Future, in Medium Term Public Investment Outlook (2012-2016) and in successive annual budgets. But, an opinion poll conducted by the Business Times-Research Consultancy Bureau (BT-RCB) revealed that Sri Lanka has a shortage of skilled workers.

Sri Lanka ranks relatively low in the productivity/competitiveness in her labour force. In order to transform Sri Lanka into a knowledge-based economy by 2020, as envisaged in the Mahinda Chinthana, drastic changes in the skills development have to take place. Changing the structure of the national economy combined with rapidly changing technology, increasing income of people, and modernization of lifestyles and global links will open up new employment opportunities with specific technical knowledge and skills. Further, overseas employment is a high potential target market for skilled workers. Thus the skills development would take a prime place in the development agenda.

The skills development sector has made a significant headway over time through policy interventions and programme implementation. A considerable amount of funds has been invested in the sector through Treasury allocations supplemented by donor funding. The improvements are visible in both inputs (infrastructure and capacity) and in outputs (curricular, quality, NVQ and  competency standards). Despite its steady expansion over the years skills development is yet to become the dominant, societal and industry-preferred mode. The sector suffers from several deficiencies. Mismatch, employability, quality, relevance, social recognition and industry acceptability are prominent among them. Addressing the issue of mismatch, while meeting the industry expectations, satisfying the social aspirations, translating the policy priorities and fulfilling the economy needs is a challenging task.

competency standards). Despite its steady expansion over the years skills development is yet to become the dominant, societal and industry-preferred mode. The sector suffers from several deficiencies. Mismatch, employability, quality, relevance, social recognition and industry acceptability are prominent among them. Addressing the issue of mismatch, while meeting the industry expectations, satisfying the social aspirations, translating the policy priorities and fulfilling the economy needs is a challenging task.

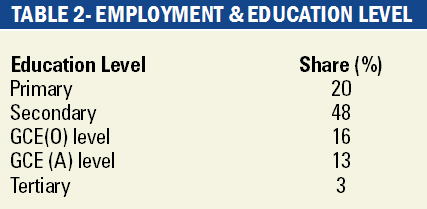

Mismatch is found between a) target population and the capacity; b) demand and supply; c) expected quality and quality delivered; and d) sectors catered and neglected. Total capacity of existing training institutions is two thirds of the target population as shown in Table 1. There is a shortfall of 141,500 in the capacity available for skills development over the target population in the country.

Increasing capacity coupled with improvement in quality and relevance is the immediate current requirement in the skills development.

The mismatch prevailed in the skills development sector has affected the effectiveness and the impact of skills development on the economy:

(i) Formal training in skills development is deprived annually to a considerable number of youth. This has pushed them to seek and secure employment in the informal sector. The opportunities available in the informal sector are low income earning, underemployed and economically technologically backward.

(ii) Three quarters of the demand for skilled labour abroad is not being met. This limits exploiting the full potential and benefits of overseas employment opportunities. Nearly half of the overseas employees are domestic workers.

(iii) Employers have reservations on the quality and relevance of skills development training. A study by NAITA (2005) revealed that only 37 per cent of respondent companies were prepared to consider trainees from public institutions for recruitment.

In such a background, attention should be concentrated upon strengthening the delivery capacity, improving quality, access and relevance, increased industry participation and being demand driven of the skills development training. These options are complimentary to each other. Accordingly, a strategy reflecting a combination of these options should be adopted. It is targeted to create a knowledge-based economy with emphasis on developing identified priority sectors, improving the productivity in the agriculture and manufacturing sectors, promoting skilled worker migration and facilitating a sizable growth in the SME sector. Meeting manpower requirements for this is not an easy task.

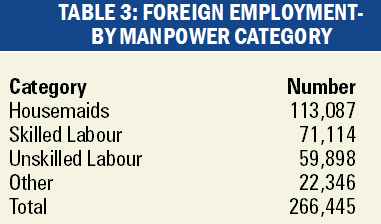

The employed labour force in the country has surpassed eight million today. Agriculture accounts for 32 per cent, industry and services sectors account for 25 per cent and 43 per cent, respectively. According to the Global Competitiveness Report-2011/2012, Sri Lanka ranked at 52nd position in terms of labour market efficiency and 85th position in technological readiness. This reflects the presence of an inefficient labour market (117th). The share of the total employed with different levels of education is indicated in Table 2.

Considerable proportion (nearly 70 per cent) of the labour force is with less education and training.

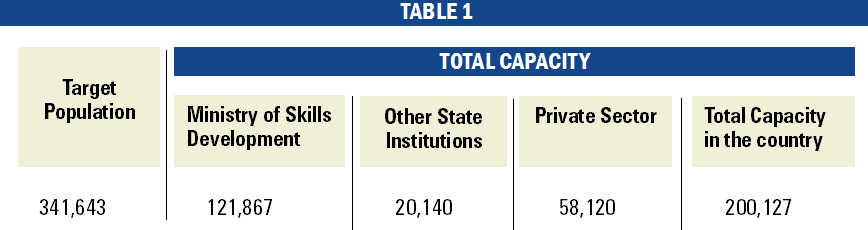

Migrant labour, in terms of employment, foreign remittances and other social economic benefits, constitutes a significant portion of the Sri Lankan labour force. As shown in table 3, majority of the migrant workers are unskilled and they are employed in lower paid jobs abroad. This has considerably reduced the potential benefits of overseas employment. Individual migrant workers are unable to earn a sizable decent income while the country is declined of potential for increased remittances. Out of a total of 266,445 migrant workers in 2010, only 27 per cent were skilled labour denoting a low education and training level of the majority.

Skills development has failed to attract adequate social recognition as an equal alternative to higher education. Skills development is poorly perceived and often seen as the reserve option – it is for those unable to achieve the grades to enter into higher education. It is meant for the so-called dropouts. There is a widely-held view that people who are academically weak undertake technical and vocational education. This has made technical education and vocational training (TEVT) little or even not attractive to youths and their parents limiting young people going into vocational training. TEVT, in its current form, is facing a serious recognition issue among aspirant youths, parents and employers.

Mahinda Chinthana – Vision for the Future has identified several sectors that would contribute to enhance output and employment.

(i) Tourism and Hospitality,

(ii) ICT

(iii) Construction

(iv) Light Engineering and Manufacturing

The employment growth prospects of these sectors are expected to continue in the future. The Department of National Planning has estimated the total skills development training requirements in the economy considering the projected development targets. This stands at 182,333 for 2016 and 178,896 for 2020. Out of the total projected training needs for the next 10 years 60 per cent would arise in above four sectors; tourism and hospitality, ICT, construction and light engineering and manufacturing.

“With respect to employment and skills development, the policy of the government is to provide continuous training and retraining to workers in different disciplines. A workforce equipped with contemporary technical skills and knowledge will be created through advanced vocational training. A proper mechanism to encourage collaboration between training institutes and industry will be established to optimize the utilization of available human resources.” Mahinda Chinthana – Vision for the Future

It is obvious that there is an urgent need to strengthen the national skills development training system with expanded access to quality training in a positive response to the labour market needs in a changing economy. The providers of training particularly in the state sector should pay adequate attention to such changes and development in the labour market. It is necessary to make adjustments with respect to skills standards, curriculum development, practical training, and introduction of flexible, modular courses, staff development, student evaluation methods, and industry linkages. There should be serious concerns to enhance quality and relevance of and recognition for skills development training. Skills development should not be a stop-gap arrangement or an option available to dropouts only. It should be an equal option and opportunity available to the youth along with university education. Given the potential for development and the priorities placed in Government policy documents, there is a strong need to improve the quality and relevance of skills development training and realign the supply of skills to the demands of the labour market and the economy. It is late but better being late than never, to rethink and reorganize the skills development training to suit labour market needs in a growing economy. Skills development, a sector with unlimited potential and prospects should be transformed to ‘Prestige’ from ‘Prejudice’.

(The writer can be reached on

chandra.maliyadde@gmail.com)