Sunday Times 2

The right to be forgotten in the digital age

Globalisation and the universal nature of the Internet and social media have led to a significant loss of control over an individual’s personal data. They pose a difficulty in understanding the consequences and after-effects of disclosing one’s personal information online. They say the Internet never forgets, however bold new laws are, to keep what is private private.

This week the European Court of Justice put privacy ahead of the freedom of information in a landmark ruling, which allows people to ask for their personal information to be taken off from the index of public search engines in line with a EU Data Protection Directive that regulates the processing of personal data within the European Union.

The ruling of the ECJ essentially decided that Internet privacy, and the right to be able to personally manage your online presence, is a basic human right to be protected; a right now recognised as the right to be forgotten.

This ruling has far-reaching ethical implications, not only for Europe but for the rest of the world, including Sri Lanka, as it signifies the importance of balancing what is in public interest and a person’s right to a private life.

This inability to maintain control over one’s personal information was a problem even before the advent of the digital revolution, when improper circulation and misuse of information occurred through wiretapping, identity theft and the misuse of customer data by companies. However, the emergence of social media platforms with easy access to a person’s information has made the control and protection of data a crucial concept. Under the EU Data Protection Directive, the right to be forgotten is a means by which individuals can now regain control over what is rightfully theirs.

In an increasingly digital society, personal data have become a new form of currency. While the collection of user data has become a main source of funding for seemingly “free” services such as search engines, social networks, news sites and blogs, there is no clear technology or regulation in place which enhances a user’s privacy needs or requirements.

People must have the right to determine what information of theirs should be on the internet, and this includes principles of necessity, proportionality, data minimisation, transparency and the right to ask for a limited period of data retention, rectification or deletion.

Although such binding legal requirements such as the “right to be forgotten” is difficult to implement or enforce, many quasi legal measures such as self-regulation, data minimisation are sufficient to secure a person’s control over their data for the time being.

Prof. Jefferey Rosen writes in the Stanford Law Review that “in theory, the right to be forgotten addresses an urgent problem in the digital age; it is very hard to escape your past on the Internet now that every photo, status update, and tweet lives forever in the cloud.”

The other precedent that was set by the court ruling was the EU’s ability to enforce a Spanish court decision in a case involving an American company. The Spanish court ruled that US firms can no longer “hide behind” the fact that their physical servers are based in other parts of the world and that even non-European companies must comply with this rule.

In addition to this, the right to be forgotten can also be declared not only against the publisher of content such as Facebook or a newspaper but also against a third party such as Google or Yahoo. For example, in December 2013 the Spanish data protection authority fined Google for failing to comply with the country’s privacy practices. The authorities alleged that Google did not provide sufficient information to its users on what purposes the data collected about them served.

Advocates of free speech have said this ruling may pave the way for the rich and powerful to conceal incriminating information about their past as well as for criminals to delete references of their past crimes.

Similarly, it has been argued that this suppression of legitimate public information could be seen by many as an act of censorship that could lead to the erosion of democracy and the limiting of society’s existing right to the freedom of expression and the freedom to record history. It also raises the important question of whether or not people should be allowed to rewrite or erase history.

The issue of censorship is a pertinent question. In certain Asian countries the Internet is being placed under strict censorship and government control. This intolerance is mirrored across Southeast Asia as governments look at sites like Facebook as a way for media to go against them and censorship is used as an attempt to stem brewing dissent.

For example, in Thailand the government reached an agreement with YouTube to block selected items. The government and the army also maintain teams of watchers to monitor web boards and other sites for inappropriate content while social media was being monitored closely for violations of the new censorship rules. Stricter media controls are also being applied elsewhere in the region.For instance, in Singapore new licensing rules governing online news sites bar sites from posting content that “undermines racial or religious harmony”. According to these rules, any prohibited content should be removed within 24 hours of being notified by authorities. Similarly other countries such as China and Vietnam censor search results from Google and deny their citizens access to social media such as Facebook, Twitter and YouTube.

For Sri Lanka such drastic curtailing of the freedom of information is not an option as such a move will only affect a citizen’s freedom to access information. Besides, it will also have an adverse effect on the country’s economic potential, dampening e-commerce and discouraging investment, because international companies take into account a country’s policy on internet censorship before investing.

The Government has recognised that the Internet and social media should continue to dominate the flow of news and information around the world through the implementation of the Electronic Transaction Act. Through this Act the Government puts in place the proper legal framework to facilitate domestic and international electronic commerce. This was done in order to encourage the use of reliable forms of electronic commerce, to promote public confidence in the authenticity, integrity and reliability of data messages and electronic communications and to promote efficient delivery of government services by means of reliable forms of electronic communications. This has ensured that electronic communication is officially and legally accepted as a proper means of communication.

Computer literacy in Sri Lanka is increasing, especially with the government taking measures to increase it from 35 per cent up to 75 per cent within the next two years.

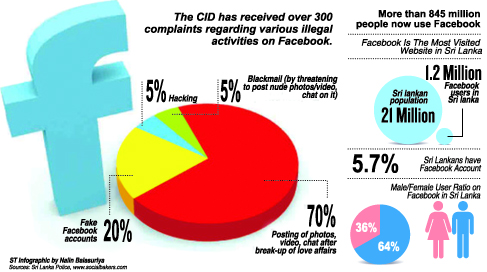

Similarly, there is a significant growth in Internet connectivity and social media usage in the country. Statistics show that currently there are more than 1.2 million Facebook users in the country, which is 60 per cent of the total Internet users and 5.64 per cnet compared to the country’s population. The largest age group using Facebook are the 18-24 year olds, with the majority of them being male.

The age distribution of Facebook users and the male to female user ratio are shown in the graph.

While social media sites are revolutionising the way people interact in communities, it should be noted that around 20 per cent of Facebook accounts in Sri Lanka are reported as false. This gives us an indication of the potential social media has for the misuse of information to be used for malicious or fraudulent purposes.

Any harmful images and derogatory comments about individuals tend to have irreversible and long-term consequences. Since the Internet is for life, this kind of defamation can stay with people for a long time and a person’s digital identity can follow them wherever they go. This breach of society’s privacy is creating a culture that can cause irreparable harm to people’s reputation and disturbs their peace of mind.

In a democracy every person has certain inalienable rights that must be respected. One of them is the right to free speech. However there should be established criteria for social media, on the one hand to uphold the constitutional rights of citizens to the freedom of expression and on the other to prevent miscreants and troublemakers from misusing social media for harmful purposes.

There is an argument made by some that Internet presence in social media websites is vital to adequately take part in the 21st century. Whatever the arguments are it is unquestionable that privacy is a universal right and measures to protect it are long overdue. The ECJ judgment in data protection is the first step towards establishing a coherent law to protect a citizen’s right to privacy when it comes to online information and affords us a glimpse of the direction in which the law may develop in the future.

I hope that in the light of this “right to be forgotten” becoming recognised and its practical effects being reverberated around the world, it will raise awareness and engage the public in discussions on internet privacy and security and how they can be furthered to serve the interests of the country.

(Charitha Herath graduated from the University of Peradeniya, Sichuan University in China and Ohio University in the United States. He is the Secretary to the Ministry of Mass Media and Information.)