Melioidosis the great mimic

View(s):

Dr. Enoka Corea

Dr. Enoka Corea, Senior Lecturer in Microbiology, discusses an infectious disease that is sometimes hard to identify. Kumudini Hettiarachchi reports It is a great mimic, sometimes making it difficult to catch it in the act, but now Sri Lanka is identifying and treating it effectively.

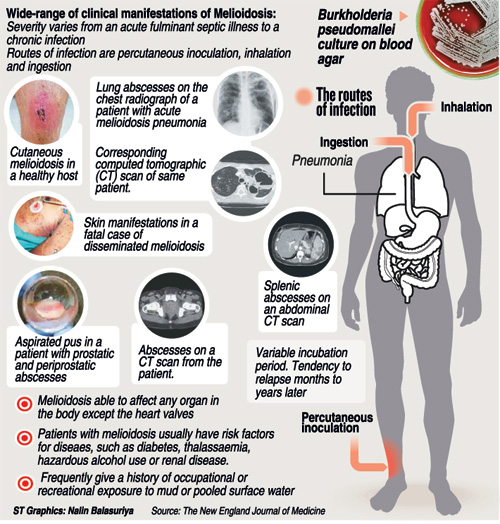

The culprit is none other than Melioidosis, an infectious disease caused by the tongue-twister bacterium – Burkholderia pseudomallei, MediScene understands, which can mimic not only tuberculosis but also pneumonia.

While conceding that there are a lot of questions still unanswered and stressing that it is not considered a public health emergency, Dr. Enoka Corea, Senior Lecturer in Microbiology at the Colombo Medical Faculty, is poring over literature as well as the microscope, while making presentations to doctors on identifying the disease early and preventing death.

There have been 10 reported and confirmed cases of Melioidosis in 2013, with one fatality, and so far four confirmed cases in 2014 and another three suspected cases. It takes different shapes under the microscope and that is why sometimes it is difficult to identify, leading to the death of patients, she cautions.

Before getting down to the nitty-gritty of lifting the bacterium out of the soil where it is found in abundance and and pointing out its features and also the symptoms caused by it, Dr. Corea explains that Melioidosis is found in the tropical belt, close to the Equator where Sri Lanka is located.

A “notorious” trait of Melioidosis, according to her, is its “variable” incubation period or the time between infection and appearance of symptoms. While no one is exactly sure how the bacterium enters the body, once it does enter it can remain there with no sign of illness from 10 days to many, many years. Dr. Corea cites the case of an American war veteran of World War II who manifested symptoms of Melioidosis after 62 years!

The exposure to B. pseudomallei can come from anywhere – for it is a soil saprophyte (a bacterium that grows on dead or decaying organic matter), especially fond of muddy soil found in paddy-fields, she points out, adding that as such anyone may get infected. “It is not a primary pathogen (something which causes disease), but an accidental one, acquired by exposure to soil and water. The mode of transmission is not very clear but it is most likely to enter the human body through the skin and mucous membranes. Inhalation plays a role when soil or water is aerosolised, for example during heavy rains and floods. Ingestion may play a role in small outbreaks due to a common water source,” she says, adding that any cut or wound on the skin could act as an entry point.

Who is at risk?

Who is at risk?

Those at highest risk, according to Dr. Corea, are people who have occupational exposure to soil and water such as paddy farmers, other cultivators, military personnel, construction workers, livestock farmers and even those who indulge in gardening.

There could be an upsurge in numbers affected by Melioidosis after a natural disaster such as a flood or cyclone, MediScene learns, as Dr. Corea regrets the fact that no major study was done after the devastation of the 2004 tsunami in Sri Lanka, although both Aceh and Phuket in Indonesia had produced such cases. After a storm in Galle, three patients had also been reported.

A strong alarm she sounds is that it can have variable clinical manifestations, presenting as “almost any kind of syndrome, affecting any system”. It also has a tendency to relapse, even after being treated successfully the first time.

For identification of the disease, the “gold standard” is a culture. However, it is easy to culture but difficult to identify, says Dr. Corea, adding that as the disease can be rapidly fatal, there is an urgent need to increase awareness among clinicians and microbiologists. “There should be ready access to blood cultures and wider availability of microbiology services.”

“Serendipitous is what I thought at the time and serendipity played a role in that discovery of many of the cases we diagnosed over the years,” she says, adding that it seems as if the disease that has historically-infected humans may have remained unrecognized.

What are the symptoms of Melioidosis?

The symptoms could vary from mild to major, says Dr. Corea, pointing out that there could be involvement of almost any site of the body.

The range of symptoms is immense – from chronic localised infection with abscess formation to acute fulminant septicaemia. There could be skin, psoas (an important muscle in the lumbar region), splenic, liver, lung or even brain abscesses, septic arthritis, pneumonia, cavitating (cavity-causing) pneumonia, pleural effusions and lymphadenitis (inflammation or enlargement of a lymph node). There could also be septicaemia (blood poisoning) or brain-stem encephalitis (inflammation).

It is also an “opportunistic” infection and even though many may get exposed to the bacterium, those with diabetes, chronic renal failure, renal transplants, thalassaemia, alcoholism and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) are more vulnerable, MediScene learns.

Significant milestones

The historian in Dr. Corea cannot resist the passage of B. pseudomallei down the corridors of time, uncovered through literature surveys. Here are the significant milestones:

- Melioidosis had first been described as a “glanders-like” disease more than a hundred years ago in 1913, by Capt. Alfred Whitmore who was based in Rangoon, Burma. Although glanders, an infectious disease caused by B. mallei, can affect humans, it primarily affects horses, donkeys and mules.

- In 1921, A.J. Stanton and W. Fletcher had discovered Melioidosis in Malaya, with the name being proposed by the former. (‘Mel’ is derived from Greek, with ‘meli’ meaning ‘distemper of asses’; ‘oid’ — ‘similar to’; and ‘osis’ — ‘condition’.)

- Sri Lanka had also been one of the first countries to report a case of Melioidosis, with a case of infection in a European published in the Ceylon Journal of Science in 1927. Based on this case, the early editions of textbooks of tropical disease had listed Ceylon as endemic for Melioidosis.

- In Howe’s review of 1971, this single case of Melioidosis had earned Sri Lanka a place on his map.

- Twenty years later, without a further case being recorded, David Dance seems to show Sri Lanka as endemic for Melioidois, though it is possible that two cross-hatches were enough to shade the whole country.

- There was one tantalizing report of a Belgian tourist who may have been infected in Sri Lanka but no further reports of indigenous transmission and Sri Lanka was quietly dropped from textbooks and relegated as a country with sporadic case reports.

- By the time Cheng published his review, Sri Lanka had recorded its first case in a Sinhalese, but it was published in the local journal, and may not have been accessible to him.

- The recent history of Melioidosis began in 2006 with Peradeniya Professor of Microbiology, Prof. Vasanthi Thevanesam, being asked to look at an unusual isolate from a blood culture. She recognised it as Burkholderia pseudomallei and was searching online for information on the management of the patient when she stumbled on Tim Inglis. An exchange of e-mails and the patient was well on the road to recovery. Unfortunately, this was not the case for the next patient who was dead before the blood culture isolate was identified.

- It did not take long for Tim to arrive with his “lab-in-a-suitcase” to set about confirming the identity of the two isolates and “infecting us all with the bug”, says Dr. Corea.

- Shortly after he left, there were two more cases, one from a postmortem blood sample sent to Dr. Corea by the Colombo Medical Faculty’s forensic dept. Thereafter, the numbers increased, with 2013 recording 10.