A wanderer through the landscapes of time

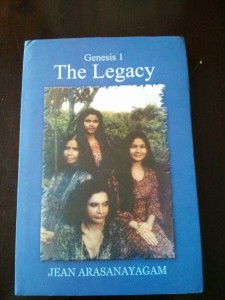

To anyone who knows her, it is clear Jean Arasanayagam is her own most penetrating, most persistent interrogator. In a dance that her readers are familiar with, Jean asks the questions and then finds the answers in her poetry and prose, in fact and fiction. This is nowhere more evident than in latest collection of verse. Intended to be part of a trilogy, ‘Genesis 1: The Legacy’ brings us over 20 poems from one of the island’s most beloved voices. In them the poet confronts the ghosts of her ancestors, seeing in the mirror the face of colonizer and colonized, she asks, ‘What do I call myself, what do I cling on to,/ why do I, centuries later search for the roots of this mixed identity the blood from the melting/ pot of the nations, poured into my veins flowing/ through my arteries, tinting my complexion?’

In an intimate introduction, Jean describes this collection as an extension of her “never ending search for identity…a self-questioning and self-investigation that is continuous…” Jean’s gaze is determinedly unflinching, her resistance to “exoticizing” or “valorising” her  ancestors set in cement. She begins as she means to go on when early in her introduction she notes with ironic amusement that “there is a cut-off point where a relationship that has yielded progeny does not reveal the name or race (mixed, native or otherwise) of the mother – that all important but unknown secret cipher which generated all those future bloodlines.”

ancestors set in cement. She begins as she means to go on when early in her introduction she notes with ironic amusement that “there is a cut-off point where a relationship that has yielded progeny does not reveal the name or race (mixed, native or otherwise) of the mother – that all important but unknown secret cipher which generated all those future bloodlines.”

In records and letters, wives and mothers were variously described as “a Burgher lady who died in childbirth” or “most probably a lady of European descent….” Jean tells the Sunday Times over an email from her home in Kandy. Still, in one of the most moving poems in the collection Jean finds room to honour her own mother whom she describes as “a mix, delightfully formed, of several cultures.” She remembers the work of her mother’s hands, her “be-ringed fingers” kneading the dough for breudhers, preparing transparently thin pannekojes and a hundred other exquisite treats. “With her alive, there were no days of penury/her generous heart gave us all she had…” Again and again, Jean is compelled to return to her mother’s deathbed in verse, drawn there by “a burning need” for forgiveness, by the remnants of an old dream.

As she strays between the boundaries of the real and the illusory, Jean acknowledges freely that her quest demands more than a strict adherence to historical record. “I found that I am history and have become my own witness, recorder, documenter and even self-creator of a distinctive identity—I can use not only factual knowledge but also create my own fictions and I rove, a wanderer and traveller through the landscapes of the centuries.”

At the beginning of ‘An Invasive Inheritance’, she asks “What’s this inheritance I am always talking of?” Her answers are necessarily part fiction, but they are engagingly and gamely fleshed out nevertheless, full of empathy for those long gone. ‘What do those people to whom I am allied/ however tenuously in my diluted bloodstream, /spend their guilders or rix dollars and stuivers on…’ Jean imagines state banquets, decanters of wine poured into glasses monogrammed with the insignia of the VOC but also the lives of common soldiers, ‘who would never return, never see their kith and kin again,’ or those who met their ends on ‘long tedious voyages, sick with scurvy/ or starvation, ill-paid, without predictable/ futures, flotsam and jetsam washed up on the/shores of colonialism.’

But one man survives to makes his presence felt in the collection. When she first began her “historical sleuthing,” Jean was able to find interesting details about the French part of her ancestry – Jean Francoise Grenier left behind a son Francois Grenier, who was named a ‘ward of the state’ after the death of his mother and the departure of his father on a military mission. As in the poem about her mother, Jean uses food as beautiful illustration of life; a metaphor for change, resilience and intermingling. ‘What did Francois eat here?’ she asks, imagining not brioche and croissants but food flavoured with the coveted local spices and salt bartered from the Kandyan king’s territory. To Jean food is politics, history and community and so she imagines it being to Francoise Grenier.

“I was able to come upon many facts about his entry into the VOC during the latter part of the eighteenth century,” Jean says now. “My maternal grandmother was the great granddaughter of Jean Francois, Charlotte Camilla was one of eight siblings. All this information is not only documented in the DBU (Dutch Burgher Union) journals but there are also accounts from the Grenier’s Family Album, the Wapenheraut(the armorial Herald) as well as Joseph Grenier’s (my grandmother’s first cousin) autobiography ‘Leaves from my Life’.”

The last is among Jean’s treasured possessions. It is counted among the tangible and visible artefacts inherited from her family, the most important of which she considers her family home. “Within the house, hard fought for and eventually establishing the family name there (it is named Jansz house) do remain valuable artefacts,” says Jean. “There have been tremendous losses with time.Irretrievable losses, which can never ever be replaced.” Artefacts have migrated with family members but Jean has saved letters and books, some porcelain, furniture and china as well as the Solomons family Bible with genealogies. “I wish I had preserved my mother’s Singer sewing machine which dated from the 1920s perhaps,” she says, “but I just gave it away, a Kodak camera, a gramophone, HMV wireless, jewellery, furniture, porcelain – even a wedding dress of a precious friend bought in England, the marriage was in 1940.” Jean sees all these artefacts as having played an important part in “contextualizing” her identity.

Though she initially struggled to wrestle the complicated narratives that emerged from a lifetime of such investigations into the structure of a trilogy she found it taking shape over time. “For me the entire project was taking a fascinating turn and I was going deeper and deeper into what would become my own Testament—contemporaneous with its witnessing, recording and documentation,” she writes. For part 2, she is considering publishing ‘Waiting for the Call’ a play that she ‘resurrected,’ and‘re-edited’; so that it could become a bridge between the segments of Genesis.

“As for the final part of the Trilogy “Tryptich” I have constructed a vast architectural literary edifice which will embody Genesis One and Genesis Two – an epic finale… it will be detailed, comprehensive and has emerged from my own life, experiences, mindset, imagination,” promises Jean. Like the letters and books that fuel her self-examination, she imagines her own work will become an artefact, her family inheriting her questions and answers after she is gone. “It is not just self-knowledge alone I am seeking but its widening, widespread extensions that will reach those who want to know.”