‘Settling’ the Nile in a personal way

Among the world’s great rivers, the Nile undoubtedly occupies a unique position in every culture. For a start, it is the world’s longest river at more than 4100 miles (slightly longer than the Amazon). It was also the birthplace of Egyptian civilisation: “the gift of the Nile”, according to the ancient Greek historian Herodotus, because of the river’s annual flood that fertilised its valley and the surrounding desert. Moreover, long before the rule of the pharaohs, in prehistory, the Nile valley was the route by which our earliest ancestors migrated from their origins in east Africa and populated the rest of the globe.

Last but not least, there was the source of the Nile: a challenging mystery for two or three millennia. In the ancient world an extraordinary range of individuals were curious to locate the source, such as Alexander the Great and Herodotus from Greece, Cyrus and Cambyses from Persia, Julius Caesar and Nero from Rome. The Romans even had a proverb, Nili caput quaerere, Latin for ‘to search for the head of the Nile’. It meant: to attempt the impossible, to cry for the moon. No definite progress was achieved until the era of the Victorian explorers of Africa, men like Richard Burton, John Hanning Speke and David Livingstone. In a telegram to the Royal Geographical Society in 1863, Speke claimed to have “settled” the source of the Nile as Lake Victoria—an enormous body of water named by Speke, who was the first European to see it. His claim generated a notorious controversy with his former co-explorer Burton, who favoured Lake Tanganyika, eventually concluded in favour of Lake Victoria. But in reality, even today, the true source of the Nile is far from settled.

era of the Victorian explorers of Africa, men like Richard Burton, John Hanning Speke and David Livingstone. In a telegram to the Royal Geographical Society in 1863, Speke claimed to have “settled” the source of the Nile as Lake Victoria—an enormous body of water named by Speke, who was the first European to see it. His claim generated a notorious controversy with his former co-explorer Burton, who favoured Lake Tanganyika, eventually concluded in favour of Lake Victoria. But in reality, even today, the true source of the Nile is far from settled.

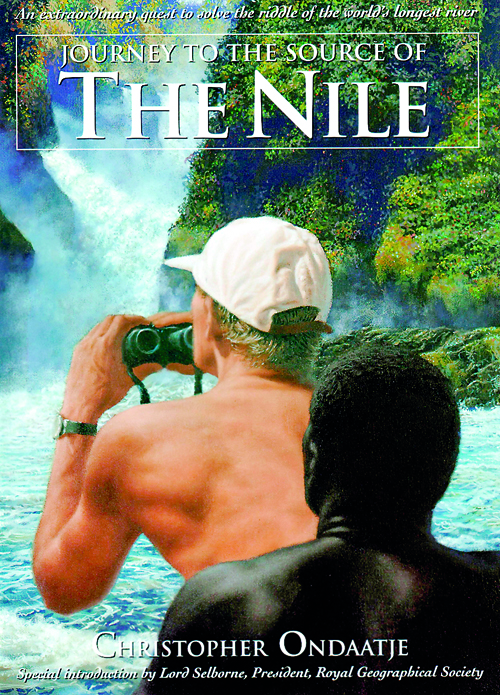

In the 1990s I too became mesmerised by the subject. I read practically everything that had been written by the explorers about the labyrinthine network of rivers and lakes that at long last become the Nile near Khartoum in Sudan, where the White Nile flowing from the south joins the Blue Nile rising in Ethiopia. Then I realised I would have to do some exploring of my own. I would have to stand on the banks of those rivers, lakes and waterfalls and see for myself the direction of the currents and the forces that shaped the mighty river, and fit them into my own mental jigsaw puzzle. I wanted to ‘settle’ the Nile in a personal way, as I describe in my book, Journey to the Source of the Nile, published in 1998 with an Introduction by Lord Selborne, the President of the Royal Geographical Society.

One of my photographs in the book shows a plaque above the Ripon Falls at the northern end of Lake Victoria, which overlooks the place where the Victoria Nile begins its outflow from the lake towards its far-off delta in Egypt. The plaque carries the following words in honour of Speke’s discovery: “This spot marks the place from where the Nile starts its long journey to the Mediterranean Sea through central and northern Uganda, Sudan and Egypt.”

It is an appealing notion, and yet the statement underplays a key fact about Lake Victoria: it is a reservoir fed by other rivers. The lake’s main feeder river, located on its western edge, is the Kagera River. This river itself has two main tributaries: the Ruvyironza (later Ruvubu) River, which rises at Mount Kikizi in Burundi, and the Nyabarongo River, which rises at Mount Bigugu in Rwanda. These two feeder rivers meet near Rusumo Falls on the Rwanda-Tanzania border. Either of these springs has a better claim to be the source of the Nile than Lake Victoria. The spring on Kikizi is the furthest south, whereas the spring on Bigugu lies furthest from the Mediterranean in river miles: 4,238 miles to be precise, 36 miles further than Kikizi.

Although Speke in due course came across the Kagera River on his second expedition, he did not give it much attention in his Journal of the Discovery of the Source of the Nile. Clearly he must have realised that this new discovery would raise a serious question mark over his claim for Lake Victoria as the source. For the Kagera is a significant river, as I saw for myself while crossing it in 1996. Indeed, the Kagera is much wider than the Victoria Nile after the Ripon Falls, though lacking its swiftness and cataracts.

John Hanning Speke

Following the river from Lake Victoria to Lake Albert throws up a further complication about the source of the Nile. It flows for 300 miles until it reaches Murchison Falls, and eventually flows into the north-east corner of Lake Albert—a difficult spot to reach not only because of the river but also because of the hostile local inhabitants. We got there on foot with the help of two ‘friendly’ hired guides and entered a small village harbour with painted fishing boats and a few fishermen. When I asked them the name of the river they replied as expected: “the Victoria Nile”. But when I pointed at the sun glistening on yet another river about 400 yards to the west flowing out of the lake to the north, they replied: “the Albert Nile”. “Not the Victoria Nile?” “No Sir. The Albert or White Nile.” Then I realised for the first time what is not generally understood. The Victoria Nile does flow into Lake Albert—but it does not flow directly into the White Nile, it mixes with the much more saline waters of Lake Albert. Most of the water in the lake, the Nile’s second great reservoir—as much as 85 per cent—comes not from the Victoria Nile (and ultimately from the Kagera River) but rather from another big river, the Semliki, which joins Lake Albert at its southernmost point. The Semliki River flows from Lake Edward, through the western edge of the great Ituri Rain Forest in Zaire (now Congo), augmented by streams from the Northern slopes of the Ruwenzori Mountains -the “Mountains of the Moon”. Thus, the Ruwenzoris are just as important a source of Nile water as is Lake Victoria.

Ironically, scientists now know that Lake Tanganikya, too, was at one time a source of Nile water, as claimed by Burton and Livingstone. Not during the 19th century, but millions of years ago. There is much still to learn about the geological history of the Nile, but there seem to have been five major episodes in the evolution of the river since the evaporation of the Mediterranean Sea about six million years ago, known as the Eonile (the oldest), the Paleonile, the Protonile, the Prenile and the Neonile (with deposits indistinguishable from those of the present river). During the Eonile period Lake Tanganyika actually drained northwards into the Nile, until the eruption of the Virunga volcanoes—south of the Ruwenzoris—blocked the river’s course in Rwanda. The Eonile was therefore much lengthier than the present Nile, with its headwaters as far south as northern Zambia.

Such volcanic activity was part of the massive plate-tectonic activity between Africa and Asia that created the Great Rift Valley in East Africa, which includes Lake Tanganyika, and the uplift of the Tibetan plateau in Asia. By around five million years ago, the Rift Valley was fully formed, and there were also climatic changes, which produced savannah. In the savannah, two features of modern humans evolved, primarily because they were essential for survival. About six million years ago our ancestors developed an ability to walk upright, followed much later by a massive expansion in brain capacity. By about 1.8 million years ago, four new species of hominin had appeared in East Africa, many of which were discovered during the mid-20th century by Louis and Mary Leakey in Olduvai Gorge in the Rift Valley. In other words, the evolution of our ancestors may well have been triggered by the very same geophysical events that formed the present headwaters of the Nile.

So, although the 19th-century obsession with determining the geographical sources of the Nile may now be part of history, the search for the source has acquired a fresh dimension, of which I was only partly aware when I published my book. This would surely have greatly surprised—and probably horrified—the Victorian explorers, who could never have imagined Africa as the cradle of the human race. If both the source of the Nile and the origins of humankind can be said to owe their existence to the formation of the Rift Valley, then European explorers did not ‘discover’ this part of Africa; they returned it to the land of their first ancestors.