Columns

Allies abandon Govt. in its Motion against UNHRC intervention

The Government could not have chosen a worse time to bring a Motion to Parliament with the hope of winning bipartisan support against moves by the United Nations Human Rights Commissioner (UNHRC) to begin an international investigation against Sri Lanka. Far from winning any new support, the Government, in fact, lost support for the Motion from its own constituent parties, in the wake of the flare up of violence against the Muslim community living in the Aluthgama and Beruwela areas, that coincided with the two-day debate in the House.

Sri Lanka Muslim Congress (SLMC) members led by Justice Minister Rauff Hakeem, as well as Industry and Commerce Minister Rishard Bathiudeen, who backed the Government when a ‘No-Confidence’ vote was taken up against it less than a month ago, decided to stay away from the House when the vote on the Motion was taken up on Wednesday evening.

A visibly angry Minister Hakeem who participated in the debate on Tuesday, instead of extending his support for the Government motion, said he could not help but agree with the allegations made by the UNHR Commissioner Navi Pillay about growing religious intolerance in the country. ”She (The UNHR Commissioner) noted that a group of Sinhala extremists led by Buddhist monks were spreading religious intolerance and inciting religious hatred and violence, and this is exactly what has happened in the last few days in Aluthgama. Are we ourselves paving way for another international inquiry?” the Minister questioned in the House.

Saying he was both “disillusioned and despaired “by the turn of events, he said that the lack of assurances for the safety of Muslims in the country is troubling.

Government members who spoke, chose to avoid the communal clashes in Aluthgama, instead choosing to play one of their favourite cards, that of evoking memories of the hard won war victory. An impassioned plea to uphold the Constitution and safeguard the sovereignty of the country came from UPFA National List MP Janaka Bandara who introduced the Motion. He made an especially valiant effort to arouse a sense of patriotism from among fellow parliamentarians, but at least among some sections of the UNP legislators present, MP Tennakoon’s speech seemed to have had the opposite impact, with many bemused by his tone of speech, than impressed by it.

The decision to allow another National List MP A.H.M. Azwer to second the Motion also did not help further the Government cause.As UNP Matara District MP Mangala Samaraweera pointed out, if the Government was serious about winning more support for a Motion that seeks to oppose a UN investigation against the country, someone senior like Prime Minister D.M. Jayaratne, or Leader of the House Minister Nimal Siripala De Silva, should have moved the Motion.

However, the fact that a group of backbenchers moved the Motion did not prevent most senior Government members from participating in the debate. Among those who spoke was Construction, Engineering Services and Housing Minister Wimal Weerawansa, a notable absentee during last month’s No-Confidence motion debate. he made a brave attempt to rekindle a sense of patriotism with the play of words which he is noted for, but despite making a fiery speech, falling back too much on conspiracy theories did little to win any new support for the Government’s Motion.

He may have wanted to woo members of his former Party, the JVP, who were seated across him in the House, by saying ,”It was this kind of foreign intervention against which Comrade Wijeweera (Founder of the JVP) fought against all his life,” but the JVP MPs did not seem moved by his reminisces.

Instead, JVP‘s new leader, MP Anura Dissanayaka while saying they were opposed to any international inquiry against Sri Lanka, said his Party was introducing several amendments to the Government’s Motion, that seeks a guarantee that it would inquire and report within three months, into a host of other human rights violations that have occurred in the country since the war ended.

The Government did not accept the amendments, which prompted the JVP MPs to leave the Chamber when the vote was taken. The UNP too introduced several amendments to the Motion which included a call for the full implementation of the recommendations of the Lessons Learnt and Reconciliation Commission, as well as the re-introduction of the provisions of the 17th Amendment to the Constitution. These too were rejected by the Government, However, the UNP decided to remain in the House when the vote was taken, but abstained from voting. The Government passed the motion comfortably with 134 votes in support, while the 10 Tamil National Alliance (TNA) MPs present, voted against it.

On the face of it, the decision to ask Parliament to vote on the UNHRC matter seemed like a smart move on the part of the Government. But its failure to win over the Opposition and garner support for the motion means passing it in Parliament will have little bearing on a now near certain UN initiated inquiry against the country.

The public petition – A forgotten tool of Parliament

Petitioning parliament is a long established democratic tool that was adopted from the British parliamentary system. In the words of the former Secretary General of the Sri Lankan Parliament, Priyanee Wijesekera;

Petitioning parliament is a long established democratic tool that was adopted from the British parliamentary system. In the words of the former Secretary General of the Sri Lankan Parliament, Priyanee Wijesekera;

“The public petition enables a citizen to bring to the notice of Parliament the flaws in the administrative machinery of the Government, and seek redress for grievances suffered. There is no limit to the subjects on which petitions may be presented and neither is there any limitation on the number of petitions which may be presented”.

Once an MP files a petition on behalf of a citizen, it is referred to the Committee on Public Petitions for their consideration. The Committee has wide ranging powers to recommend the granting of relief, and prior to doing so can inquire and obtain information from public officials and institutions.

In this sense, it can be a powerful tool within a democracy, where empowered citizens can seek redress for their grievances on an unrestricted range of topics. However looking at the petitioning statistics provided by Manthri.lk, a pioneering parliamentary monitoring website, the minimal use of petitions is apparent.

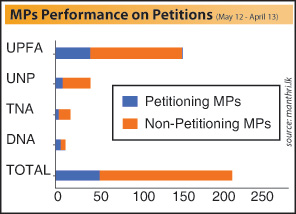

In the year, 1st May 2012 – 30th April 2013, only 26% of MPs (59 of 225 MPs) ever used their right to facilitate the petitioning of parliament. As shown in the graph above, within the governing UPFA coalition 45 MPs (28%) had filed petitions, and within the main opposition UNP, only a mere 8 MPs (18%) had done so.

In the year, 1st May 2012 – 30th April 2013, only 26% of MPs (59 of 225 MPs) ever used their right to facilitate the petitioning of parliament. As shown in the graph above, within the governing UPFA coalition 45 MPs (28%) had filed petitions, and within the main opposition UNP, only a mere 8 MPs (18%) had done so.

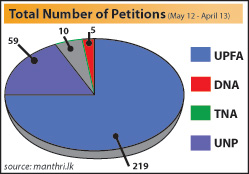

In absolute terms, UPFA MPs account for 219 of the 293 petitions filed, a resounding 75%. This is roughly in keeping with the 72% of parliamentary seats that the coalition occupies. UNP MPs filed 59 petitions, which at 20% of the total petitions is directly proportionate to the 20% of seats that the party occupies.

The number of petitions filed by MPs, whilst roughly proportionate to party representation, is not however indicative of optimal performance. When taking a closer look at the data, it becomes apparent that the Hon. Minister of National Languages and Social Integration, Vasudeva Nanayakkara, is leagues ahead of other MPs in petitioning for citizens. He solely accounts for 105 petitions, 36% of all petitions for the year in question.

The performance of Vasudeva Nanayakkara raises the question ‘why only him?’. Unfortunately why petitions are so infrequently used by MPs cannot be answered definitively. One scenario is that MPs are unaware of the straightforward system of petitioning (Standing Order 25A), coupled with a lack of faith in its ability to function effectively. Another is the ability of a citizen to petition the Parliamentary Ombudsman directly, but this is less likely given that most citizens are unaware of public petitions as a mechanism for relief.

The bridging of this information gap, along with an efficient system of responding to petitioners and general cross-party consensus on the value of the petitioning framework, will provide one significant step towards delivering Sri Lankan citizens with a more accessible system of democratic governance. If you have any questions on how a petition can be made, please contact one of your MPs (contact details on their profile pages on Manthri.lk). If you do not find the contact details of your MP, please email questions@manthri.lk and we would be happy to assist you.