The Knight who befriended ‘Elephant Man’ visits ‘Elephant Island’

“The approach to Ceylon was heralded by a token in the sky, by a baldachin [rich brocade] of white clouds. These were the first clouds that had been visible in the heavens for many months of this journey. In India the clouds had been forever the same – a windless desert of turquoise blue, glaring, hot and empty.” – Sir Frederick Treves, The Other Side of the Lantern: An Account of a Commonplace Tour around the World (1905)

In 1976 I had the pleasure of working in Sri Lanka with the renowned but then little-known British actor John Hurt as co-producer of the film East of Elephant Rock, directed by another soon-to-be-recognised British cinematic talent, the independent filmmaker Don Boyd.

Recognising Hurt’s ability and versatility I subsequently followed his career with interest. His next film, which set him on the road to stardom, was Alan Parker’s Midnight Express (1978) – alas an inaccurate, dishonest and racist prison movie based on a ‘true’ story – that earned him a Golden Globe Award for Best Supporting Actor (Motion Picture).

While his acting in Midnight Express was distinguished – and sartorially distinctive as he wore a sarong in his prison cell acquired in Sri Lanka the year before – it was David Lynch’s The Elephant Man (1980) that brought forth from him a superlative performance under extraordinary conditions. This situation arose because Hurt played “The Elephant Man” who, it will be remembered, was a severely disfigured person of the Victorian era with a head resembling an elephant, accentuated by the cloth that covered his deformity.

Hurt’s performance in this film (shot in black-and-white), which could have so easily been hampered by such an encumbrance, was recognised with the bestowal of the BAFTA Award for the Best Actor in a Leading Role. In addition, The Elephant Man was nominated for eight Academy Awards (Oscars), including that of Best Actor for Hurt.

The screenplay was adapted by Lynch from The Elephant Man and Other Reminiscences (1923) by Sir Frederick Treves. The son of a humble upholsterer, Treves was born in 1853 in Dorset, England, and attended the London Hospital Medical School. He became a prominent surgeon during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, specialising in abdominal surgery. He performed the first appendectomy in Britain in 1888 and was subsequently appointed a Surgeon Extraordinary to Queen Victoria.

Following Victoria’s death in March 1901, Treves was appointed an Honorary Sergeants’ Surgeon to her successor, Edward VII, prior to his coronation. However, two days before ascending the throne Edward was diagnosed with appendicitis, which was usually not treated by surgery and carried a high mortality rate. Treves, however, drained the infected appendix through a small incision.

Despite this medical expertise Treves is better-known as the surgeon who befriended “The Elephant Man”. Reviled by Victorian-era society, Joseph Merrick – his real name – made a living by appearing in freak-shows. Treves first saw “The Elephant Man” in 1884 being exhibited in a shop across the road from the London Hospital where he worked. Two years later Treves brought Merrick to the London Hospital: there he lived until his death in April 1890.

A still from the movie The Elephant Man

As a result of Treves’ relationship with “The Elephant Man” there have been several fictional portrayals of the physician in the telling of the story. For instance Treves is one of the lead characters in Bernard Pomerance’s play The Elephant Man (1977) as well as David Lynch’s film, in which he is played by Anthony Hopkins. Treves’ great-nephew, also Frederick, acted in the film, but didn’t take the role of his relative; perhaps because his age didn’t match, or, more likely Hopkins was a bigger attraction.

At the beginning of the 20th century Treves made a world tour that he documented in an excellently perceptive and poetic travelogue, The Other Side of the Lantern: An Account of a Commonplace Tour around the World (1905). His account of Ceylon, alas unknown to Sri Lankans, begins with Chapter VIII, “The Capital City of Ceylon”, in which he writes of the appearance of clouds, absent during his sojourn in India, a passage I quoted at the beginning of this article. “Now that we had come upon clouds the world had changed,” Treves continues. “The sky was kindly and nearer to hand. It had stooped down to the hill-top, and had crept into the valley, while over the town it could be touched by the children’s kites.

Caricature of Sir Frederick Treves by “Spy” from Vanity Fair (1900)

“As the vessel steams along close in shore, it is evident that we had come at last to the island of the story book. Here is the very beach which has figured so vividly in many a tale for boys.”

Treves’ storybook remark was no doubt figurative, as children’s fiction set on the island prior to his visit was not that numerous. The best 19th-century book of the genre was Lost in Ceylon: The Story of a Boy and a Girl’s Adventures in the Woods and the Wilds of the Lion King of Kandy (1861), by William Dalton, which was indebted to Robert Knox’s account of his 19-year confinement in the Kandyan kingdom. Another children’s novel worth a mention is Through Peril to Fortune: A Story of Sport and Adventure by Land and Sea (1880), by Louis F Liesching.

The following paragraphs reveal Treves’ imaginative descriptive powers that overwhelm the prose of the typical travel account of the period:

“Here is a coral reef where the indigo-coloured sea breaks up into roaring lines of foam,” Treves continues, “while within the reef the leisurely swell tumbles upon a yellow beach. This is the ‘adventurer’s island’, for here is a red headland, with a grassy knoll, and a clump of palms upon its summit which must have been a pirate’s look-out. There is even a dark cave filled with the sea, and there can be little doubt that at its tunnel end is a small, dim beach where a boat could land with treasure to be buried.

“The coco-nut trees come down to the water’s edge. They make a deep background of shadows, among which can be seen a forest of bare trunks, standing erect like a crowd of masts in a harbour. There is a rock between the forest and the beach, and from its shelter rises upwards a curling line of smoke – a wreath of Gobelin-blue [Gobelin, a state-factory of tapestry in Paris; Gobelin-blue, like that used in Gobelin tapestry] against the purple aisles of the wood. By this fire a buccaneer must be sitting, counting his ‘pieces of eight’, with his flint gun by his side, his faithful dog, his parrot, and his comic bo’sun. Though seen for the first time, the brilliant shore was familiar, and if Robinson Crusoe [an apt example as there are some who believe Crusoe was based on Robert Knox] and Friday were searching in the sand for turtles’ eggs it would seem more familiar still.”

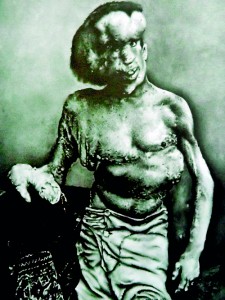

The ‘Elephant Man’ Joseph Merrick

“Colombo lies upon a level plain about the circle of its harbour. It looks bright and comfortable from the sea, and, like the rest of Ceylon, looks very green. Half the houses are lost among the trees. A grey lighthouse dominates the town with no little dignity.

“There are shops where anything can be purchased from patent medicines or flannel shirts to Paris hats or a gramophone. On the causeway outside the shop is a man, nude except for a loin cloth, crouching over a native basket filled with strange fruits. He is the merchant of a thousand years ago.”

“The mixture of the restless inventive European and the unchanging native is a striking feature of the settlement. If a motor launch broke down outside the harbour it would probably be towed ashore by a long barrow canoe propelled by paddles and steadied by an outrigger fashioned by a log of wood. Such a boat should be able to trace its pedigree to the days of Noah.”

“Just outside Colombo is a delightful marine drive called the Galle Face Esplanade. Along this road will be seen smart rickshaws, each drawn by a damp, never-tiring coolie, while now and then a trim governess car will go by, to which is harnessed a pair of trotting bullocks. Well-dressed ladies, half-naked Cingalese, wholly-naked children, Indians in gorgeous turbans and brilliant robes, and a couple of British soldiers, each with a cane under his arm, will be among the loiterers along the road. Everything is so strange, so unusual in colour, so anomalous, that it is a matter almost of surprise to note that the waves break upon the beach with just the same sounds that echo along the Marine Parade at Brighton.”

Treves was equally enthusiastic about the suburbs: “All around Colombo is a country of glorious gardens. No other capital in the world has such suburbs. There are avenues of palms with just a glimpse of the white sea between their crowded trunks, hedges ablaze with the scarlet hibiscus, thickets of rustling bamboo, lanes that lead through banana groves, the apple-green fans of which shut out everything but the sky.

“Such gardens, too, there are about the bungalows as can be seen nowhere but the tropics! Such glens full of wildest undergrowth! For fields of wheat there are fields of cinnamon, for meadows there are rice swamps, for cherry orchards are copses of mango and bread fruit trees, for the hop garden is the brake of sugar cane.”

Chapter IX, the “Cingalese and their Dealings with Devils”, is a shrewd analysis by a leading physician – and liberated thinker – of the value of devil dancing in treating disease: “The theory is old and worthy of respect as are many less ancient theories as the fons et origo mali [‘the source and origin of evil’]. It may be considered to represent in an allegorical form the bacterial basis of disease, which is a leading feature of modern pathology.”

Today it is generally believed that the visual representation of the masks used in the devil dance is of significance to modern medicine. In “Sri Lankan sanni masks: an ancient classification of disease” (British Medical Journal, December 21, 2006), authors Dr. Mark S. Bailey and Prof. H. Janaka de Silva argue that “the classification of disease used in Sri Lankan sanni masks is still relevant today”.

Treves was taken into a room by a doctor and shown a man lying on a bed, who, for a demonstration of casting out disease by way of devil dancing, was assumed to be afflicted by typhoid fever.” In front of the sick man was a board upon which was painted a gigantic demon or devil. He was very red, and his teeth and eyes were fearful beyond words. He was so contorted by fury that the frown upon his brow was terrible to see. About him were many mystic signs, which would convey to the uninitiated some of the horrors of the unknown. The make-believe invalid held in his hand a string the other end of which entered the body of the devil about the region of the heart.

“The quiet of the sickroom was now broken in upon by two grotesquely dressed men, one of whom beat hysterically upon a drum, while the other went through a series of contortions which included all the muscular possibilities of epileptic fits, mania and demoniacal possession. I gathered from the native physician that his desire was to cast the devil of typhoid fever out of the man and to make it enter the blood-curdling figure on the board.

“The man who beat on the drum now smote it like hail from a thunderstorm, so as to fill the bed-chamber with a crashing and chaotic din. His colleague at the same time fell into a series of the most fearful fits I have ever witnessed. Dreadful convulsion shook him as a terrier shakes a rat, he seemed to have as many revolving arms as a Hindu god. The contortions of hydro-phobia, lock-jaw, and strychnine-poisoning combined would be languid and leisurely in comparison with the alarming movements of this healer of the sick.

“The invalid trembled gently on his couch, like a kinematograph figure. The string twitched. Then in a moment the drum ceased, the convulsed man fell under the bed, the physician smiled proudly and bowed. He had triumphed.”

Chapter X, “The Wild Garden”, is a magnificent evocation of Kandy and the Hill Country. “The railway from Colombo to Kandy is probably the most beautiful that any train has ever traversed. The road winds up among hills covered to their summits with the glorious vegetation of the tropics, until it reaches the face of a commanding precipice at whose base lie stretched the domain of the evergreen island.

“From this height one looks down upon the Wild Garden of the World, upon upland and dell, thorpe and towering crag, smooth slope and jagged ravine, all massed with romantic imagery, all budding with eager life.

“Miles below is a river winding through a plain. Out of the plain rise hills, one upon another, ever mounting skyward until they are lost in the damask peaks on the horizon. On to the plain valleys open, which wind among the hills to end in a purple haze. These are Valleys of Sleep, any one of which may lead to the Palace of the Sleeping Beauty. They are nearly choked by rustling leaves of every shape and size, and every tint of green.

“The jungle in the wild garden is a real jungle; not a starving moorland as in India, but a forest through which a way can only be made with a hatchet, and where in the first clearing reached one would fear to find, dangling against a patch of hazy sky, a writhing python.

“There are terraces in this garden, but they are hewn from the face of precipices, while from their margins creepers hang into the void like dropping banners. There are alcoves and arbours whose roofs are groined with green, but they are as lofty as a cathedral nave.

“A scented and voluptuous wind blows through these silent glades, while in every still valley and breezeless bay among the words a warm haze lingers like a cloud of incense.”

Chapter XI bears the self-explanatory title “Kandy and the Temple of the Frangipani Blossoms” (although I have no space for the frangipani blossoms). “Kandy is a little brown town in the hollow of a sumptuous tropical valley, where it lies on the margin of a quiet mere. Much of the history of Ceylon clings about this drowsy old city by the lake.”

“The hills guard the lake and hide it as if it was a sacred thing. A breeze can scarcely find its way through the jungle to trouble the surface of the pond, which lies bare like a mirror, so that on it are reflected the avenue of palms by the foot-path and the leafy hills beyond.

“Roads wind up the sides of these slopes, but they are hidden by the crowding trees which sigh ever over the lake. On the wooded heights are houses with chocolate-coloured roofs and white walls, but they are masked by the jealous thicket.

“There grow around Kandy certain trees which are, I think, the most beautiful thing in the world” Treves declares of the Spathodea campanulata (Sinhala name kudella gaha), which is, however, not confined to Sri Lanka although the author gives such an impression, and is internationally known as the African Tulip Tree. “They have tall, dignified heights, shapely and compact, which are crowned by masses of dark green leaves. Among this sombre foliage are scattered flowers so brilliant in hue as to dot it with a thousand splashes of vermilion.”

During Treves’ visit to Ceylon news arrived of the war between Russia and Japan: “The announcement had a disturbing effect upon the miscellaneous company of people who were travelling to seek pleasure or escape boredom. Many of the latter returned home sulkily by way of the Red Sea.”

When Treves departed Colombo for Hong Kong via Penang and Singapore he witnessed a civilian maritime encounter between the nations at war in Colombo harbour. “As our steamer sailed out of the harbour of Colombo it passed between a Russian vessel on the right and a Japanese vessel on the left. They were both passenger ships. Each flew the flag of its nation, and it may be supposed that the two crews contemplated one another, across the peaceful water, with a newly aroused curiousity.”

The book is available on the internet https://archive.org/details/

othersideoflante00treviala