Sunday Times 2

A diet of ants, slugs and other bugs gave humans a bigger brain

Working out how to survive on a diet of insects caused our brains to grow, and led to use evolving, researchers have claimed.

They say the constant challenge of finding food may have spurred the development of bigger brains and higher-level cognitive functions in the ancestors of humans and other primates.

Working out how to survive on a diet of insects caused our brains to grow, and led to us evolving, researchers have claimed (AFP)

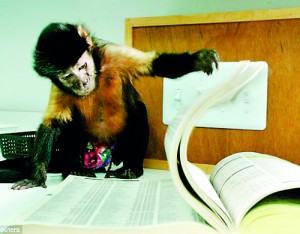

Researchers studied capuchin monkeys for five years as part of the discovery, and found they revert to insects and hard to find creatures during scarce times.

‘Challenges associated with finding food have long been recognized as important in shaping evolution of the brain and cognition in primates, including humans, said Amanda Melin of the University of Calgary, Canada, who led the research.

‘Our work suggests that digging for insects when food was scarce may have contributed to hominid cognitive evolution and set the stage for advanced tool use.’

The researchers say the five-year study of capuchin monkeys in Costa Rica, supports an evolutionary theory that links increased manual dexterity, tool use, and innovative problem solving, to the creative challenges of foraging for insects and other foods that are buried, embedded or otherwise hard to procure.

Published in the June 2014 Journal of Human Evolution, the study is the first to provide detailed evidence from the field on how seasonal changes in food supplies influence the foraging patterns of wild capuchin monkeys.

Many human populations also eat embedded insects on a seasonal basis and suggests that this practice played a key role in human evolution.

The researchers found that some Capuchin monkeys were more intelligent than others when it came to finding food (Reuters)

‘We find that capuchin monkeys eat embedded insects year-round but intensify their feeding seasonally, during the time that their preferred food – ripe fruit – is less abundant,’ Melin said.

‘These results suggest embedded insects are an important fallback food.’

Previous research has shown that fallback foods help shape the evolution of primate body forms, including the development of strong jaws, thick teeth and specialized digestive systems in primates whose fallback diets rely mainly on vegetation.

‘Capuchin monkeys are excellent models for examining evolution of brain size and intelligence for their small body size, they have impressively large brains,’ Melin said.

‘Accessing hidden and well-protected insects living in tree branches and under bark is a cognitively demanding task, but provides a high-quality reward: fat and protein, which is needed to fuel big brains.’

But when it comes to using tools, not all capuchin monkey strains and lineages are created equal, and Melin’s theories may explain why.

While Cebus monkeys are known for clever food-foraging tricks, such as banging snails or fruits against branches, they can’t hold a stick to their Sapajus cousins when it comes to the innovative use and modification of sophisticated tools.

‘Primates who extract foods in the most seasonal environments are expected to experience the strongest selection in the ‘sensorimotor intelligence’ domain, which includes cognition related to object handling,’ Melin said.

‘This may explain the occurrence of tool use in some capuchin lineages, but not in others.’

© Daily Mail, London