Sunday Times 2

How the CIA secretly published Dr Zhivago

Boris Pasternak’s famous novel Doctor Zhivago remained unpublished in the USSR until 1988, because of its implicit criticism of the Soviet system. But for the same reason, the CIA wanted Soviets to read the book, and arranged the first-ever publication in Russian.

In early September 1958 Dutch secret service agent Joop van der Wilden brought home the latest CIA weapon in the struggle between the West and the Soviet Union – in a small brown paper package.

“I had an intelligence background myself so I knew there was something very important that he had to collect and pass on,” says his widow, Rachel van der Wilden. It was not a new piece of crafty military technology, however, but a book – a copy of the first Russian-language edition of Doctor Zhivago.

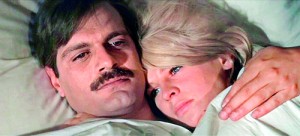

Omar Sharif and Julie Christie from the trailer for the 1965 film Doctor Zhivago (Wikimedia Commons/Trailer screenshot (Freddie Young))

“It was exciting. You wondered what was going to happen, whether it would work or not,” says Van der Wilden, who had left Britain’s foreign intelligence service, MI6, when she married and moved to The Hague the previous year.

She still has the book and the wrapping paper, with the date – Saturday 6 Sept. 1958 – written in her husband’s hand.

The book was part of a clandestine print run he had collected from the publishers and passed on to the CIA. The plan was for several hundred books to be handed out to Soviet visitors to the Brussels Universal and International Exposition, which was then taking place in neighbouring Belgium. Pasternak had long been one of Russia’s foremost poets and literary translators and it was reasonable to assume that some of the visitors would be eager to read his only novel.

It was hoped that some would take the book home and circulate it among their friends, some of whom might copy it and spread these “samizdat” copies to an even wider group.

Recently declassified CIA files published in a new book – The Zhivago Affair: The Kremlin, the CIA, and the Battle Over a Forbidden Book – talk of the novel’s “great propaganda value” and “its intrinsic message and thought-provoking nature”.

“We have the opportunity to make Soviet citizens wonder what is wrong with their government, when a fine literary work by the man acknowledged to be the greatest living Russian writer is not even available in his own country,” says one of the declassified memos.

The novel tells the partly autobiographical story of a Russian doctor and poet, Yuri Zhivago, during the turbulent decades before, during and after the 1917 revolution. He is already married when he falls in love with another woman, Lara – who is married herself, to a committed Bolshevik – and the plot follows the progress of their doomed relationship, as their lives are caught up in the monumental events of the time.

“Pasternak’s humanistic message – that every person is entitled to a private life and deserves respect as a human being, irrespective of the extent of his political loyalty or contribution to the state – poses a fundamental challenge to the Soviet ethic of sacrifice of the individual to the Communist system,” says another of the memos.

“I think what the Soviets most objected to was the spirit of the novel,” says Peter Finn of the Washington Post and co-author of The Zhivago Affair.

“They felt that it was against the revolution, that it portrayed the Soviet state in a very negative light and they simply found it unacceptable.”

Knowing his novel would never be published in the USSR, Pasternak gave typed manuscripts to a number of foreigners in 1956. They included an Italian Communist Sergio D’Angelo who was working in Moscow as a journalist and a part-time literary agent for a publisher, and fellow Italian Communist, Giangiacomo Feltrinelli.

D’Angelo wrote in his book, The Pasternak Case, about going to meet the 66-year-old author at his country house in Peredelkino, a

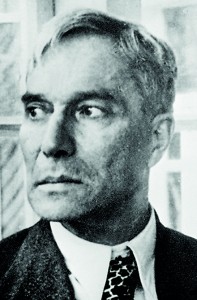

Russian writer Boris Pasternak, author of the book "Doctor Zhivago" , which was clandestinely written from 1946 to 1954. Pasternak was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1958. He was obliged by the Soviet authorities to refuse it. (AFP)

writers’ colony outside Moscow, in May 1956.

“Pasternak is in the fenced-in garden, wearing a jacket and pants of homespun cloth, perhaps intent on pruning a plant. When he notices us, he approaches with a broad smile, throws open the little garden gate, and extends his hand. His grip is nice and firm,” he wrote.

As he hands D’Angelo the manuscript, Pasternak says: “May it make its way around the world.” He then adds, perhaps ironically: “You are hereby invited to watch me face the firing squad.”

A week later D’Angelo flew from Moscow to East Berlin with the manuscript – his luggage was not searched – and handed it over personally to Feltrinelli, who signed a contract with Pasternak. Feltrinelli resisted demands from the Soviet authorities and Italian Communist Party not to publish Doctor Zhivago and it appeared in Italian in November 1957.

The CIA files reveal that MI6 had also managed to obtain a copy of the manuscript – although it is not clear how – and handed it over to the CIA. The agency then arranged for a Russian-language version to be printed in The Hague by a publisher experienced in printing Russian-language books. “They didn’t want to have any obvious involvement with America so they chose some other country to have it printed,” says Van der Wilden, who underlines that she played no part in the operation.

She believes her husband was chosen to take part because he had links to people at the publishers through their mutual involvement in the Dutch resistance to German occupation in World War Two.

The novel was handed to Soviet visitors, of which there were several thousand, by Russian emigres in a curtained-off part of the Vatican’s pavilion at the Brussels fair.

“Soon the book’s blue linen covers were found littering the fairgrounds. Some who got the novel were ripping off the cover, dividing the pages and stuffing them into their pockets to make the book easier to hide,” The Zhivago Affair says.

Word of the operation reached Pasternak who wrote to a friend in Paris: “Is it true that Doctor Zhivago appeared in the original? It seems that visitors to the exhibition in Brussels have seen it.”

Finn’s co-author, Petra Couvee says an unknown number of the books are known to have reached Moscow.

“We have found one of the copies in the Russian state library. It was intercepted by the customs and it landed in the section of the special collections, which were the banned books,” she says.

Not everyone was happy about the operation. The Dutch company that published the book had not obtained permission to do so from the rights owner, Feltrinelli, who threatened to sue. The ensuing scandal could have exposed the CIA’s involvement and a settlement had to be reached with him. To avoid such problems in future, the CIA decided to produce its own Russian-language, miniature paperback version in the US, under the name of a fake French publishing house.

Copies of it were given to Soviet and East European students at the 1959 World Festival of Youth and Students in Vienna, which was sponsored by Communist organisations. The Soviet “researchers” who accompanied the young people from the USSR reportedly said: “Take it, read it, but by no means bring it home.”

The CIA’s Doctor Zhivago project was part of a wider effort by the agency to get forbidden novels into Eastern bloc countries, including books by George Orwell, James Joyce, Vladimir Nabokov and Ernest Hemingway.

“We know that they thought literature would have an effect and they were willing to invest millions of dollars a year doing this and over the course of the Cold War it’s estimated that they brought in perhaps 10 million books and journals that circulated in the entire Eastern bloc,” says Finn.

Pasternak was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in October 1958, but forced by the Soviet authorities into renouncing it. Though he was vilified in the Soviet press, from then on, thousands turned out for his funeral when he died of lung cancer, at the age of 70, two years later.

Doctor Zhivago has sold millions of copies worldwide, and in 1965 an Oscar-winning film version was released. But it was not published in the Soviet Union until 1988, during the perestroika reforms ushered in by Mikhail Gorbachev. The USSR collapsed three years later.

(Courtesy BBC)